Winter Dreams and Youthful Fire: Michael Tilson Thomas conducts Tchaikovsky for the Original Source

The Young Conductor makes his Mark in a forever Benchmark Recording

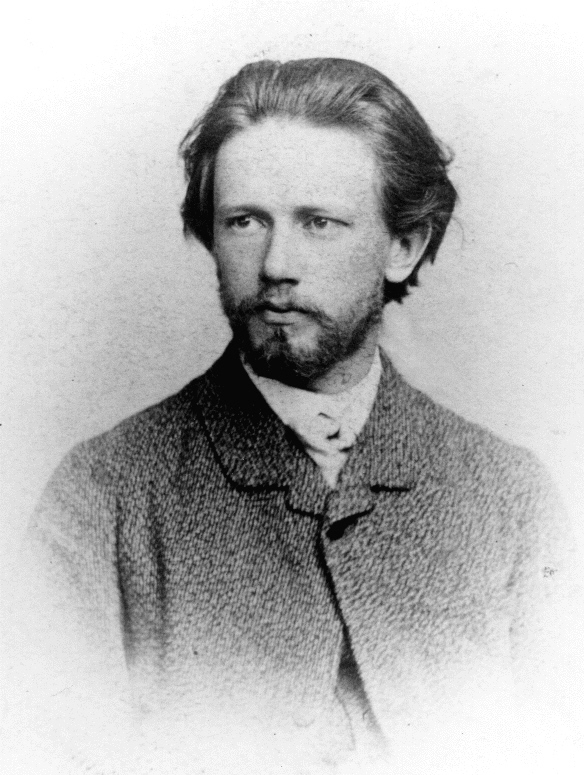

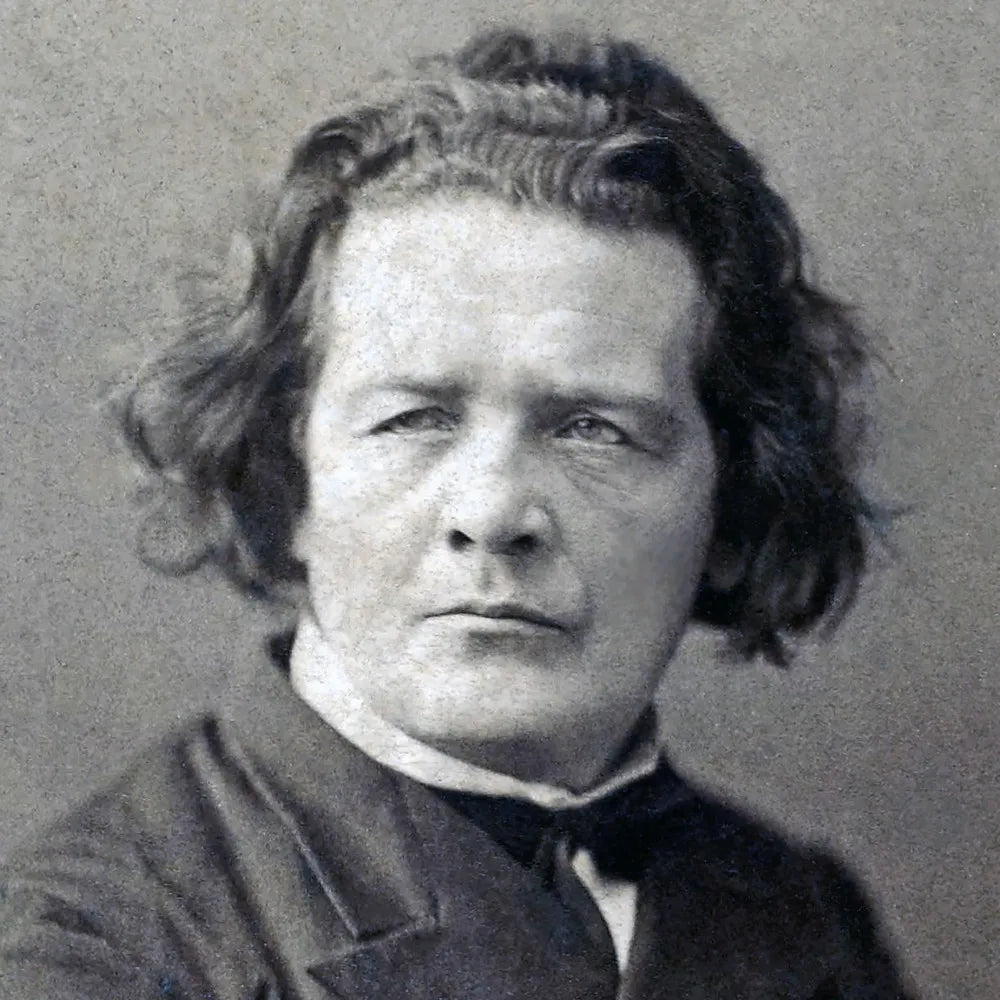

Tchaikovsky near the end of his studies in 1865

Tchaikovsky near the end of his studies in 1865

As I was mulling over my thoughts on this very special work and this utterly beguiling and enchanting recording of it - before figuratively putting pen to paper - I was trying to come up with a way to convey to someone new to classical music, or even someone more versed in it, why exactly Tchaikovsky remains one of the most unique, popular but also still most under-appreciated composers in the classical pantheon.

Under-appreciated, you scoff? Well yes. From his own day up to the present there has always been a tendency in academia, and amongst the arbiters of what constitutes the “best” classical music, to look slightly askance at the first Russian composer to gain true international stardom. The very popularity of his music with the general public seemed then - and seems now - to undermine the degree of seriousness with which he was and is taken by those who determine such things. Ah, ’twas ever thus.

And why is the music of Tchaikovsky so popular to people who’ve never even heard of Mahler or Bruckner, let alone heard a note of their music.

Because of the tunes. One fabulous, instantly memorable, instantly hummable tune after another. Over and over again. There are other strong reasons to admire Tchaikovsky’s music, and praise it to the skies - not least his, again, under-appreciated skills of orchestration - but one always comes back to the tunes.

And in this regard, as I found myself reflecting for this review, he is classical music’s Elton John: a fountain of melody, pouring out one irresistible ear-worm after another.

If I had to pick one pop song catalogue to take to a desert island above all others (as the recent LA fires recently necessitated I do), it would not be that of the Beatles, the Stones, Paul Simon, or any of the other oft-cited “greats”, it would be Elton John every time. No question.

Because of those tunes. Those irresistible, instantly hummable tunes.

You know what I mean - you’ve been humming them all your life. When you hear one of those Elton songs after not hearing it maybe for months (or years), you cannot help but feel you’ve actually been hearing it every day. The tunes are that good, that hardwired in to some part of the human brain, that they become familiar in perpetuity. They also just make you feel really good.

No one else comes close.

Except Tchaikovsky. He’s just the same. One great tune after another.

And Elton John, for all the love and acclaim that has been sent in his direction, has never quite enjoyed that critical caché enjoyed by the Beatles, the Stones, Bowie, Dylan, Mitchell, Simon and the like. Maybe it’s because he just makes it all sound so easy. The great tunes just pour out of him, like they did with Pyotr Ilyich.

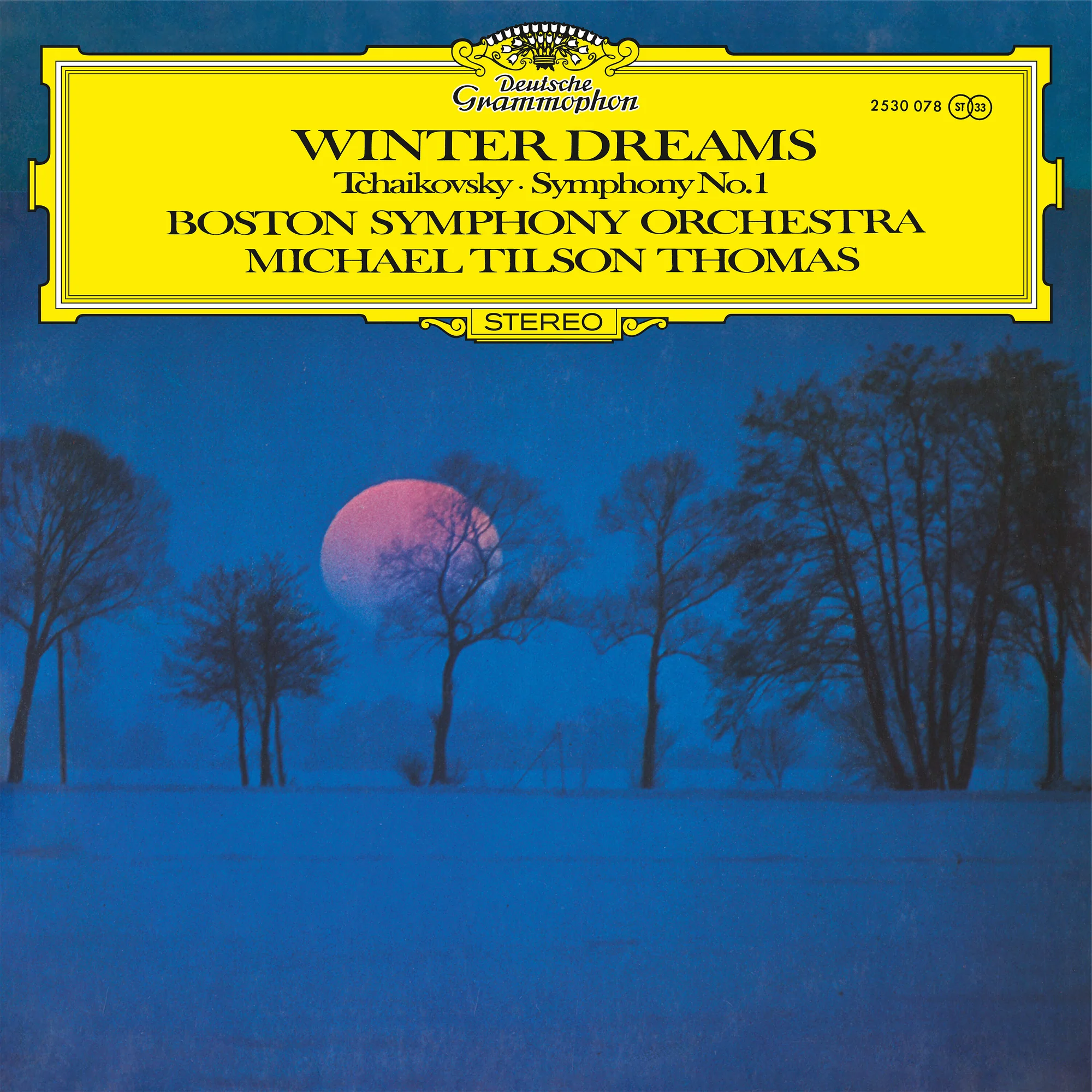

The beautiful distinctive artwork that perfectly captures the mood of this classic recording

The beautiful distinctive artwork that perfectly captures the mood of this classic recording

What I will call the “Tchaikovsky One-Great-Tune-After-Another Phenomenon” will hit you squarely between the ears within moments of dropping the needle on the deliciously gurgling opening of the First Symphony. Over shimmering strings the flute and bassoon in unison (Brahms never did that) unfurl their melody, instantly transporting you to the Russian steppe and establishing that oh-so-distinctive warm yet melancholic mood that suffuses Russian art of all kinds. It’s irresistible.

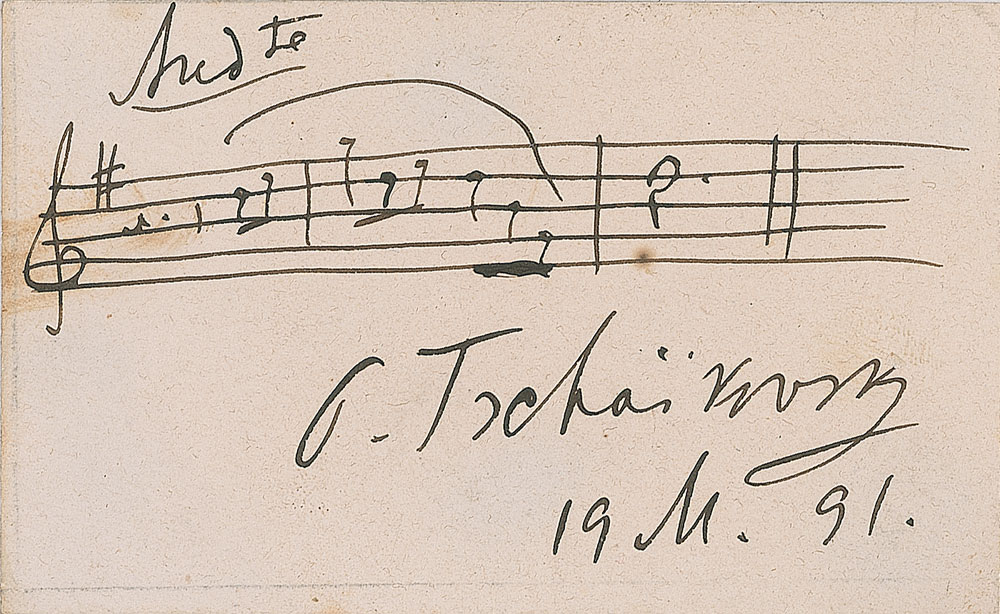

The bassoon part at the opening of the symphony's first movement

The bassoon part at the opening of the symphony's first movement

And in this recording the matchless wind players of the Boston Symphony of this period, together with the silken strings, begin their seductive airs of enchantment that will melt you into your listening chair for the duration.

The symphony’s subtitle, coined by the composer himself, is “Winter Dreams”, and dreams these symphonic movements are. You wouldn’t need to know the first movement’s heading - “Dreams of a Winter Journey” - to imagine yourself in a horse-drawn sleigh gliding through snow, maybe gazing upon the reddened cheeks of your beloved seated next to you, in your arms warm and cuddly under a blanket of heavy furs. The steady movement of the sleigh, the clip-clop of the horses, the passing landscape of bare trees, and the possibility of magic kingdoms suddenly being revealed beyond them (foreshadows of Nutcracker rides to come): it’s all there in this music of effortless, beguiling enchantment.

And it’s fully there in this equally effortless, beguiling and enchanting recording, one of the true gems of the DG catalogue, capturing one of our greatest conductors of the last half century in the full flush of his youthful mastery and vigor.

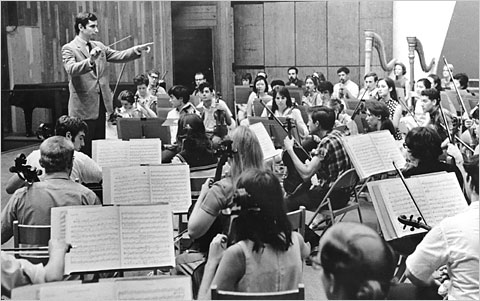

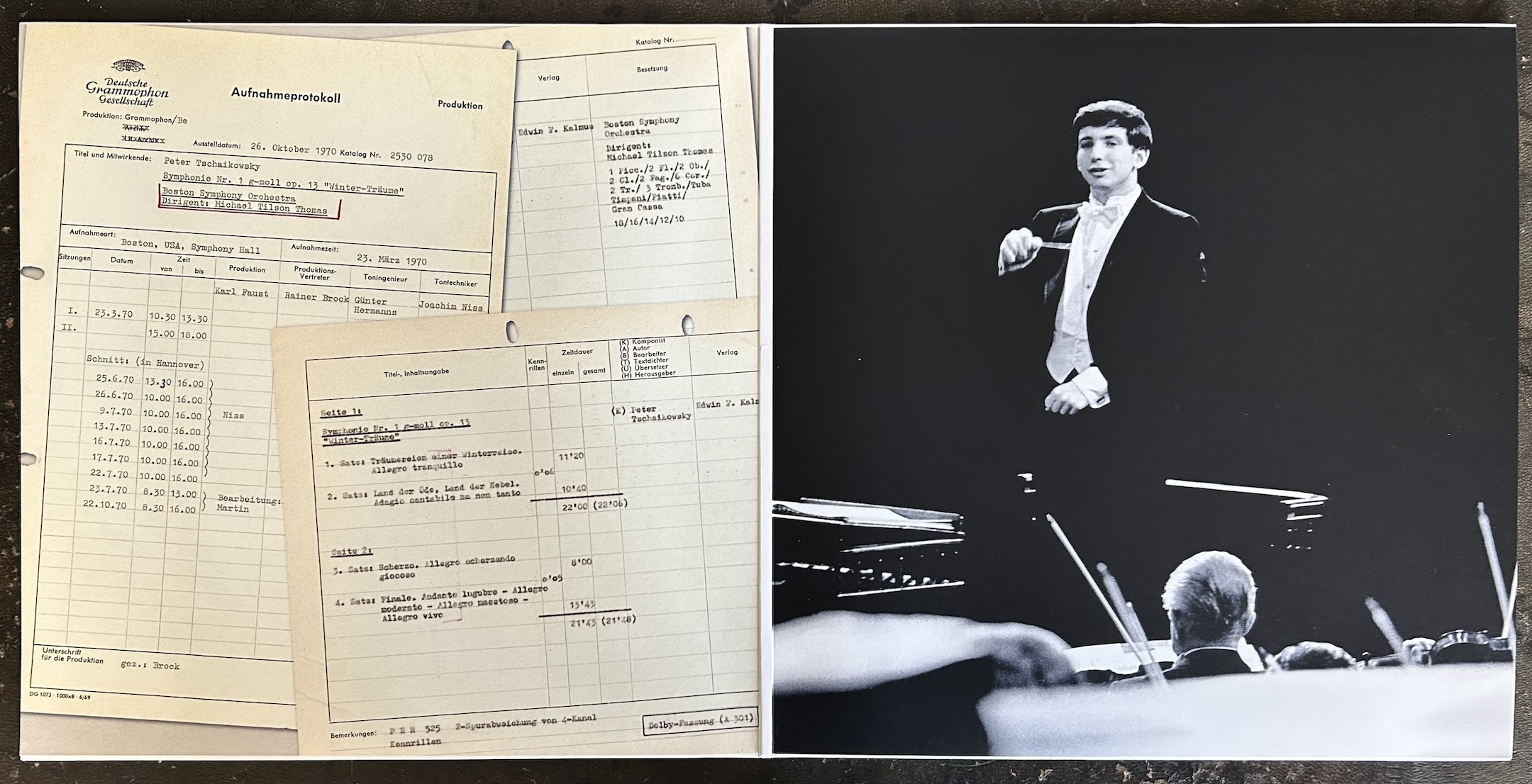

Michael Tilson Thomas conducting at Tanglewood in 1968

Michael Tilson Thomas conducting at Tanglewood in 1968

Michael Tilson Thomas made this recording at more or or less the same age as the composer was when he wrote it, and it is hardly fanciful to hear an instant kinetic connection between these two prodigious musical talents. Tilson Thomas, a protégé of the great Leonard Bernstein, similarly burst onto the national and international scene overnight when he took over a Boston Symphony concert from the unwell William Steinberg. He continued as Principal Guest Conductor until 1974. This record, released in 1971, captures musical inspiration on the fly from composer and conductor alike, and vividly conveys the full, effervescent joy of youth finding its creative feet.

How is it possible that this music of such effortless charm and assurance could have been so hard for the composer to write? And yet it was. His brother famously revealed that Tchaikovsky struggled more with this score than any other. Why would that be?

Well, as with all other composers of his generation, the 26-year old Tchaikovsky found himself caught between the strictures of the Academy - the need (nay, the order) to write in strict Germanic sonata and symphonic form in order to be taken seriously - and the more free-wheeling nationalism of the so-called “Five”: a group of Russian composers (including Balakirev and Rimsky-Korsakov) who propounded turning to folk music and non-traditional (ie. non Germanic) musical forms in order to evoke and capture a more authentic “Russian” musical voice.

Anton Rubinstein

Anton Rubinstein

Tchaikovsky turned to his former teachers at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, foremost the redoubtable Anton Rubinstein, for feedback during the composition of his first symphony, and the dead hand of the Academy almost scuttled the work in progress, as the composer's former mentors expressed dissatisfaction with what he was writing. Rubinstein himself had struggled to pen the first “great” Russian symphony - and failed several times. Similarly, the more progressive wing of the contemporary Russian musical establishment had dismissed Tchaikovsky’s earlier compositional efforts.

Yet somehow Tchaikovsky found the courage to go his own way, and rejected the changes he had implemented on the advice of his teachers. Obeying his own instincts, he went back to his original notes. He wrests triumph from the jaws of defeat. Throughout the score this symphony announces itself not only as music of instantly and unmistakably Russian hue, but as a triumphant reinvention of symphonic form in the young composer’s own image. It's full of entirely satisfactory formal procedures that nevertheless accommodate fresh surprises - like the soft coda to the first movement that returns us to that magical sleigh ride through the endless Russian snows.

And then there are the tunes. None of that Beethovenian endless variation and development of short melodic and rhythmic cells here. Instead we get full-on romantic Tchaikovsky melodies spun out gloriously to full length (take that, Academia!). This is never more so than in the second, slow movement, subtitled “Land of gloom, land of mists”. What glorious melodies and counter-melodies unfurl effortlessly across the orchestra! In Tchaikovsky’s hands this is a gloom one could be wrapped in for eternity, so inviting is it.

,-aged-8,-with-his-mother-aleksandra-(seated),-his-sister-aleksandra-(leaning-on-her-mother's-knee),-half-sister-zinayda-(standing-behind),-older-brother-nikolay,-younger-brother-ippolit,-sitting-on-father-ilya's-lap..jpg) Tchaikovsky (l.) aged 8 with his family

Tchaikovsky (l.) aged 8 with his family

The third movement scherzo could almost be out of a Russian country house production of Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream: all faery antics, colorful costumes and amorous misadventures. Then half-way through the temper changes, and we are maybe eavesdropping on quietly chattering mothers proudly watching their children perform. Over and over again listening to this recording I found myself daydreaming of another possible childhood, soft-focused and idyllic in a 19th century country house, straight out of a Russian novel, perhaps, and fairy tales. This is that kind of music and performance - it will transport you to other realms. Pure magic.

Only in the final movement does Tchaikovsky succumb to a degree of fealty to the strictures of the Academy, with a grand conclusion full of fugal counterpoint and Big Statements. But then a wistful ‘cello line will undercut the seriousness, and the brass invite a Cossackian knees-up. This is Tchaikovsky saying, “Yes I can follow Compositional Procedure - but let’s also knock back some vodka and have some fun too!”

Very, very occasionally in this performance you will hear the Boston strings fall over themselves as they try to tuck in their contrapuntal twirls, but who cares. This performance is so alive that you will forgive these tiny moments of less-than-perfection.

You will also forgive the occasionally slightly over-reverberant acoustic of Boston’s Symphony Hall. Owing to the incredibly fine re-mixing, re-mastering and cutting of the usual Emil Berliner team - Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer - details are never obscured, and the incredible dynamic range allows the deep brass to hit with that full thrilling force that is so much a part of the Tchaikovsky experience. (But the large acoustic is the reason why I reluctantly deduct one point on the absolutist scale of sound grading).

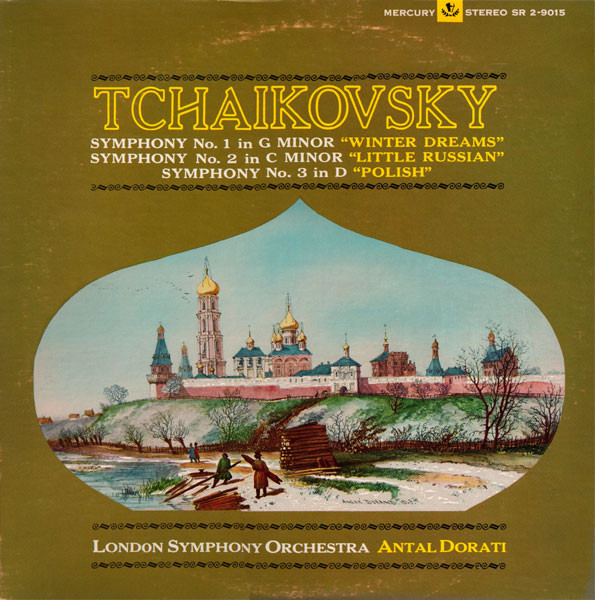

There are several lovely recordings of this symphony in the catalogue, all in very good sound. Tilson Thomas’s senior label-mate, Herbert von Karajan, committed a fine version to disc in the 1970s, best heard on the EBS remixed/remastered single layer SACD set of Karajan’s 70s Tchaikovsky cycle, one of the best out there. There’s Zubin Mehta with the LAPhil in quality Decca engineering from Royce Hall. And my other personal favorite, Antal Dorati with the London Symphony, arrives in typically immediate Mercury sound - absolutely essential for all classical audiophiles together with his spirited readings of the 2nd and 3rd symphonies.

But this Tilson Thomas/Boston Symphony version is very special indeed, even more so in its new Original Source incarnation. My 180gram pressing was immaculate, and the gatefold presentation with extra photos of the master tape boxes is in the usual handsome Original Source format. The original liner notes reprinted here rightly herald the arrival of a major new conducting talent (even if they also smack of a marketing hard-sell). Looking at the photo of an impossibly young-looking Tilson Thomas will have you marveling that such a fresh-faced lad was able to inspire the jaded, seasoned pros of the BSO to such thrilling flights of musical fancy.

And let’s just reiterate what a distinctive contribution the BSO makes to this recording, their acknowledged status as the most French-sounding of the American orchestras adding a delicious - and quite appropriate - Gallic patina to the otherwise very Slavic proceedings. Oh, and that gorgeous wind section…!

This record was just the beginning of a truly remarkable career in the studio and concert hall, and if you want to sample more of Tilson Thomas’s distinguished early years in Boston, look no further than Eloquence’s recent CD box set. (But my preference would be for a few more vinyl releases courtesy of the Original Source series - maybe that lovely record of Debussy chamber music with Tilson Thomas tickling the ivories…)

Getting back to “Winter Dreams”… How much do I love this record? Well, let’s just say this is the only record of any Tchaikovsky symphony I ever need to listen to again, and it’s coming with me to my desert island.