The Mysterious Film World of Bernard Herrmann Conjures Musical Magic and Sonic Spectacle

Looking for something a little different to put your system through its paces? Then look no further than this orchestral spectacular from one of the greatest of all film composers.

And as a recent perusal of the usual audiophile retail sites reveals, the latest limited edition reissue from ORG (Original Recordings Group) of this unique and spectacular record is very much in stock (even in some cases discounted), and so I felt it was the perfect time, indeed essential, to introduce Tracking Angle readers to this magical record.

First, some background.

The Mysterious World of Bernard Herrmann was just one of a series of records Bernard Herrmann recorded for the legendary Decca Phase 4 Stereo label in the 1960s and 70s. Many of these have long been highly sought after by audiophiles. Unlike the RCA Living Stereo and Mercury Living Presence records (or early classical Decca and Columbia/EMI releases), Decca Phase 4 made no pretense at trying to recreate a “natural” concert hall perspective. Phase 4 was all about the gear: multi-track recording that could spotlight individual instruments and fully exploit the whole stereo thing. But - and it’s an important “but” - Decca had a deep roster of excellent engineers and producers who had already produced superb sounding “regular” LPs, so Phase 4 LPs were very well recorded and mixed, albeit to highlight the wonders of multi-tracking and stereo sound.

Given the increasing popularity in the 1960s and 70s of film music, and especially certain iconic movie themes, together with the intrusion of pop music into movies like the James Bond series and The Graduate and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, it was hardly surprising that Phase 4 should start recording film music, mainly in a series of albums by Stanley Black.

But hiring Bernard Herrmann to record his own film music, as well as that of other film composers, would not have seemed the most obvious choice. His film work, albeit for major directors like Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock, was hardly as well known in its own right as Max Steiner’s romantic extravaganza for Gone with the Wind, or the more recent and rousing scores by Maurice Jarre for Lawrence of Arabia and Dr. Zhivago.

Bernard Herrmann

Bernard Herrmann

Bernard Herrmann was a modernist (albeit with a romantic soul) and his music anticipated the so-called minimalism of Philip Glass and Steve Reich. Herrmann tended to construct his scores out of short melodic fragments which he subjected to endless repetition and variation, and from unusual chord structures that would very effectively “peg” the emotion of a scene or a particular moment on screen, and then link to similar moments elsewhere in the film. While he did compose short themes for certain characters or ideas, you would not cast him in the expansive Wagnerian leitmotiv mold of composers like Max Steiner, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, or today’s John Williams, all of whom write in a more overtly late-romantic idiom. Herrmann’s scores tend towards a more concise compositional mode, more economical of means, but no less effective. He even dabbled in atonality and 12-tone procedures - which meant that film audiences watching the films he scored were unwittingly experiencing the most avant-garde classical compositional techniques while watching popular entertainment.

However, there was one particular reason why the Decca Phase 4 team would have been attracted to recording Herrmann’s film music: he delighted in exotic orchestration and highly unusual instrumental combinations - stuff that was bread and butter for the label. And nowhere was this more on display than in the series of films he scored for the master of stop-motion animation, Ray Harryhausen.

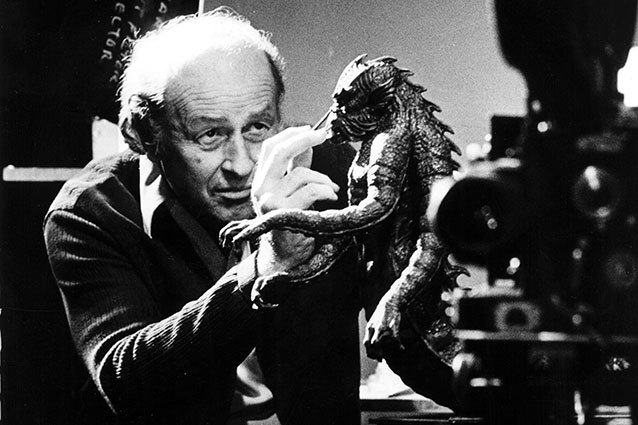

Ray Harryhausen

Ray Harryhausen

Harryhausen was an apprentice to the great Willis O’Brien, who had taken stop-motion to a new level in King Kong (1933) (a film whose fantasy elements inspired composer Max Steiner to new heights of musical imagination). Harryhausen’s early films rode the wave of 50s sci-fi and horror paranoia inspired by the atomic menace, space exploration, the Cold War, and the political witch-hunts of McCarthyism. It was a time of explosive affluence and upward mobility for many in American society, but it was also a time of deep insecurities and racial division. So in films like Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), Earth vs. The Flying Saucers (1956), and 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), that unease was exploited by having assorted stop-motion beasties rampage across the earth creating mayhem and destruction to teach meddling and dysfunctional humans something of a lesson. While these films were certainly spectacles, they were hardly profound, lacking the resonance of a film like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), for which Herrmann had provided one of his best scores, incorporating ground-breaking electronics.

It wasn’t until 1958 and the release of The 7th Voyage of Sinbad that Harryhausen hit upon the formula that was to provide him with the greatest opportunity for an endless variety of stop-motion creations, and the chance to integrate those creations into a richer storyline with more interesting human characters. For the rest of his career he would adapt myths, fantasy and sci-fi literature for the big screen, using stop-motion and his pioneering Dynamation process to make the impossible, the fantastical, come alive before our very eyes.

And, smartly, he and his producer Charles Schneer realized that having a first-class music score would be integral - indeed essential - to making the impossible not only believable, but also thrilling.

Harryhausen was all for hiring either Max Steiner (on the strength of King Kong) or Miklos Rozsa (because of his score for the 1940 version of The Thief of Bagdad). But Schneer demurred. (Rozsa would eventually score the 1974 Sinbad sequel, Golden Voyage of Sinbad). Schneer was already a huge fan of Herrmann’s music, and he set about persuading the composer to come on board. Herrmann was notoriously difficult to work with, the possessor of an ungodly temper likely to flare at any moment, and often needed endless cajoling and inducements to commit to a picture. Even an early screening of a black and white rough cut of Sinbad failed to sway him, and it took a months-long campaign by the producer to finally land the reluctant composer.

None of which you would glean from the finished results. The score for 7th Voyage of Sinbad is one of Herrmann’s finest, and gives Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade a run for its money in the Arabian Nights, musical exotica sweepstakes. It is practically a treatise on how to use the infinite variety of the orchestral palette for the most colorful effect. On an earlier Phase 4 album, The Fantasy Film World of Bernard Herrmann (1974), Herrmann featured a short suite from the film.

Herrmann went on to score three more Harryhausen films, all featured on The Mysterious Film World of Bernard Herrmann.

Cover for the Original UK Decca Release

By the time this album was released in 1975, Herrmann had made a number of successful classical and film music records for Phase 4. He was originally recommended to the label producer Tony D’Amato by the legendary conductor Leopold Stokowski, another musical maverick obsessed with sound, who was already recording for Phase 4. (Stokowski had participated in one of the earliest commercial examples of stereophonic sound when he conducted the soundtrack to Disney’s Fantasia in 1940). The opportunity to make a wide variety of records fed into Herrmann’s passion for bringing modern, often less well-known music to new audiences, as well as to record his own film scores and those of other film composers he admired. In the 1940s he had conducted regular concerts for CBS Radio, giving the American premieres of many important works, and he was an early champion of “difficult” composers like Charles Ives. By the time he started recording regularly for Phase 4 in the late 60s, Herrmann, disillusioned with Hollywood, had essentially settled in England - he was a lifelong anglophile. (I will be covering more of Herrmann’s Phase 4 albums in a future article).

Each selection on The Mysterious Film World of Bernard Herrmann features the composer’s unusual instrumental combinations, fully captured in Decca’s technicolor sound.

Things get off to a rowdy start with a suite from Mysterious Island (1961), Jules Verne’s sequel to his 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. A gargantuan orchestra that includes eight horns, four tubas, extra woodwind and percussion captures the film’s literally “larger-than-life” events as a group of Civil War prisoners escape captivity via a hot air balloon and find themselves on an island with menacing creatures from a prehistoric era. The opening Prelude and The Balloon depict their tempest-tossed escape and flight to parts unknown. I happened to be listening to this during the height of one of our recent California storms, and the music felt fully in tune with the raging elements outside my window!

The Balloon

There follow musical portraits of the soldiers’ battles with three beasties: The Giant Crab, The Giant Bee, and The Giant Bird. As you can imagine, Herrmann has a lot of fun painting these different creatures’ characteristics with his imaginative orchestration - The Giant Bee sounds like Rimsky-Korsakov’s bumblebee on steroids (supplemented by Phase 4’s interjection of bee sound effects, an entirely unnecessary addition which demonstrates just how superior Herrmann’s musical buzzing is to the real thing).

My favorite is The Giant Bird where Herrmann appropriates an organ fugue by J.L.Krebs, one of J.S.Bach’s pupils, as the raw material for a brilliant, if slightly demented, essay in counterpoint. Here Herrmann indulges in his love of wind and brass as he pits them against the rest of the orchestra.

The Giant Bird

Next comes a short suite from Jason and the Argonauts (1963), generally considered to be Harryhausen’s best film. Here Herrmann eschews any strings and instead relies on an augmented ensemble of brass, wind and percussion to create the perfect aural accompaniment to the quest to find the Golden Fleece. This is music of sharp edges and burnished metallic timbres. The film contains one of Harryhausen's most striking creations, the giant man of bronze - Talos. Herrmann's musical portrait naturally leans heavily on slow-moving brass chords - it is a perfect synchronization of visuals and music

.

Talos

I must confess that I have always found this score a little hard to take away from the picture. It does its job perfectly in the context of the film, but I find that on its own it can get a little monotonous. (But then I’m not much of a fan of brass band music either).

However, side 2 of the record yields a delicious musical feast, one of Herrmann’s most inventive and listenable scores away from the film: The Three Worlds of Gulliver (1960), based on the 1726 novel by Jonathan Swift. This was written both as a surreal adventure story and as a pointed satire of human nature and 18th century society. It was the perfect project for Herrmann who adored all things 18th century: he collected art and furniture of the period.

One of the great pleasures awaiting anyone who buys this record, and other records of various film music released at this time, is the liner-notes by Christopher Palmer. Palmer served as orchestrator, producer, and general factotum for Herrmann in the last years of his life, serving the same role for Elmer Bernstein, Miklos Rosza and others. He was also a fine composer in his own right, a music historian, and a superb writer. Just read how elegantly he describes Herrmann’s inspiration and method for this score:

“He (Herrmann) realized that the hero, being a man of the 18th century, was compound as such of such musical worthies as Charles Avison, John Stanley, the Rev. Richard Mudge, James Hook (composer of The Lass of Richmond Hill) and the Rev. William Felton, sometime rector of the parish of Diddlebury. These men provided the musical roast beef and Yorkshire Pudding of their day, and their spirit pervades Herrmann’s score in a manner not unlike that of Pergolesi in Stravinsky’s Pulcinella. Which is to say that Herrmann resorts only superficially to period pastiche, what he is really doing is interpreting his borrowings in terms of his own contemporary style, bringing the past to life in the light of the present”.

The Overture immediately establishes Herrmann’s method: a stylized 18th century dance works its way through radically different instrumental groupings to evoke the “Three Worlds” of the hero’s travels: his home in England, the diminutive realm of Lilliput, (light and airy harps and celesta) and the giants of Brobdingnag (heaving contrabass and regular tubas).

Overture

It’s really hard to pick favorites out of this score, but here are a few.

First, the musical depiction of the tiny Lilliputians, viewed not only from Gulliver’s perspective (piccolos, sleigh bells, triangles and two different sizes of glockenspiels), but he from theirs (the periodic intrusion of lower instruments with a lovely counter-melody first heard on the clarinet). Herrmann fans will no doubt notice similarities with his magical and nostalgic music that accompanies the sleigh-ride sequence in Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons.

Lilliputians 1 and 2

The score takes a brief break from pictorial effects with a gorgeous romantic cue for strings only, depicting Gulliver’s love for his fiancée Elizabeth, who shares his adventures after stowing away on his boat. As Christopher Palmer elucidates: “…. here Herrmann used as a point de depart some music by another of Gulliver’s contemporaries, Thomas Roseingrave, who went mad for his frustrated love of a pupil, but what exactly the borrowing consists of Herrmann alone could reveal, since the music bears his own personal signature in every bar”.

Again, Herrmann devotees will hear distinct echoes of the love music from Vertigo.

The Lovers

As Gulliver and Elizabeth are pursued by the giant Brodingnagians, Herrmann aptly recasts the Lilliputian musical themes for the lowest extremities of the orchestra, because now it is the two humans who are the tiny ones, loomed over by the fearsome giants. It’s a tour de force of instrumental dexterity, and again reminiscent of another classic Herrmann piece of scoring, the Mt. Rushmore chase at the end of North by Northwest.

Pursuit

And as Gulliver and Elizabeth find their way back to the “normal” world of Wapping, England, Herrmann likewise returns us to the familiar, comforting strains of the Overture’s Dance, rooted in the 18th century’s more conventional harmonic and melodic procedures.

Finale

The Best Way to Listen to The Mysterious Film World of Bernard Herrmann

This is a record best listened to on vinyl. The original Decca and London (“Made in England” must be on the label) LPs were always the way to go. There is some disagreement amongst audiophiles as to whether there is indeed a sonic difference between Decca and London (UK) pressings of Phase 4 titles. I do not hear a difference in this case.

BUT the game changer for this record is the ORG (Original Recording Group) reissue that came out on double 45rpm in 2019, mastered by Bernie Grundman, pressed at RTI. Now I am not always a fan of 45rpm reissues. While I acknowledge the generally higher quality of sound that comes with 45rpm, I hate having the music’s natural flow interrupted for side flips, especially in classical music. Here, however, we have suites of music with short movements, so flipping the record is not such an intrusion. And the sonic gains are enormous. As you can tell from the descriptions above, this is music sounding at the extremes of the orchestral spectrum, with massive clusters of brass and woodwind, brash percussion, and also high strings. This is very demanding music to record well, but clearly it was, at the legendary Kingsway Hall, home to so many spectacular Decca and EMI sessions. The ORG reissue opens up the soundstage and adds air to the instruments, so instead of the brass and woodwind being crammed together you can now clearly hear all the instruments sounding in their own space. The bass rumbles along effortlessly, and those high wind, string and percussion passages are light as air, but also slice and dice when called for.

The ORG reissue is a limited edition of 2,500, but it is very much in stock at all the usual suspects, sometimes with a discount. It’s a no-brainer purchase for all but those who are allergic to orchestral music. The suite from The Three Worlds of Gulliver in particular is worth the price of admission alone, and is one of those rare pieces of music whose sense of fun in playing with the period idiom and in juxtaposing completely different kinds of instruments just makes me smile every time I listen to it.

If you have to go the CD route I’d plump for the Mobile Fidelity Gold disc, but it will cost you around $50 used. It is the only CD version which retains the openness and air to be heard on the ORG reissue and, to a lesser degree, the original vinyl pressings. You will discern MoFi’s EQ tweaking, more on some cuts than others, but it is not so much that it will ruin the listening experience. The recent box set collecting all the Herrmann Phase 4 Film albums together was remastered at Abbey Road. Tonally it sounds closer to the original than the MoFi but - and it’s a big “but” - it’s cut pretty hot. I am not an engineer, but this suggests some degree of compression, and it will probably induce listener fatigue (as it did with me). There is definitely a bit of an edge to the sound. Why oh why do these remastering engineers do this over and over again, especially with classical? If we want to hear the music louder we are all perfectly capable of turning up the volume. As to the earliest CD incarnations of the Herrmann/Phase 4 catalogue, labelled ADRM, these CDs re-coupled different LP selections to fill the discs, omitting some scores altogether, and it’s been far too long since I heard them to comment meaningfully.

What to Listen To Next

Frankly, anything by Bernard Herrmann - he’s that good, and the scores play well away from the films themselves. Certainly investigate the series of Phase 4 albums of his and others’ film music, now neatly gathered together in a box set (though note my reservations on the remastering above).

For complete scores you can’t go wrong with the series of releases done by Varese Sarabande in the late 1990s. They are very well played and recorded, with excellent liner notes. On vinyl I also highly recommend the original soundtrack recording (though shortened) for The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, reissued on LP in Stereo by Varese in 1980 (STV 81135) . It’s a sonic stunner.

But I will also single out the Herrmann entry in the RCA Classic Film Scores series, with Charles Gerhardt conducting the National Philharmonic again in Kingsway Hall, engineered by the legendary Kenneth Wilkinson working on peak form. This has an excellent selection from the score for Citizen Kane, with the added delight of a young Kiri Te Kanawa singing for real the operatic aria mangled by the unfortunate second Mrs. Kane in the film. The virtuosic Hangover Square piano concerto a la Liszt (music to go mad to - literally) is given a thrilling outing by pianist Joaquin Achucarro, and the sound is just “Wow!!”. Then there are the vivid pictorial scores to Beneath the 12-Mile Reef, and White Witch Doctor. All kinds of weird and wonderful instruments, including the aptly named serpent - a Herrmann favorite - are let off the leash in these cues. The album kicks off with the hair-raising Death Hunt chase from On Dangerous Ground, all whooping horns (eight of them), doom-laden brass, and hammering percussion. This is simply one of the most exciting film music cues ever committed to vinyl. The British pressing is to be preferred (ARL1-0707), and will sound first class. Otherwise go for the Dutton Vocalion dual layer CD/SACD, remastered in 2-channel and surround.