The Dawn of a New Era in Berlin

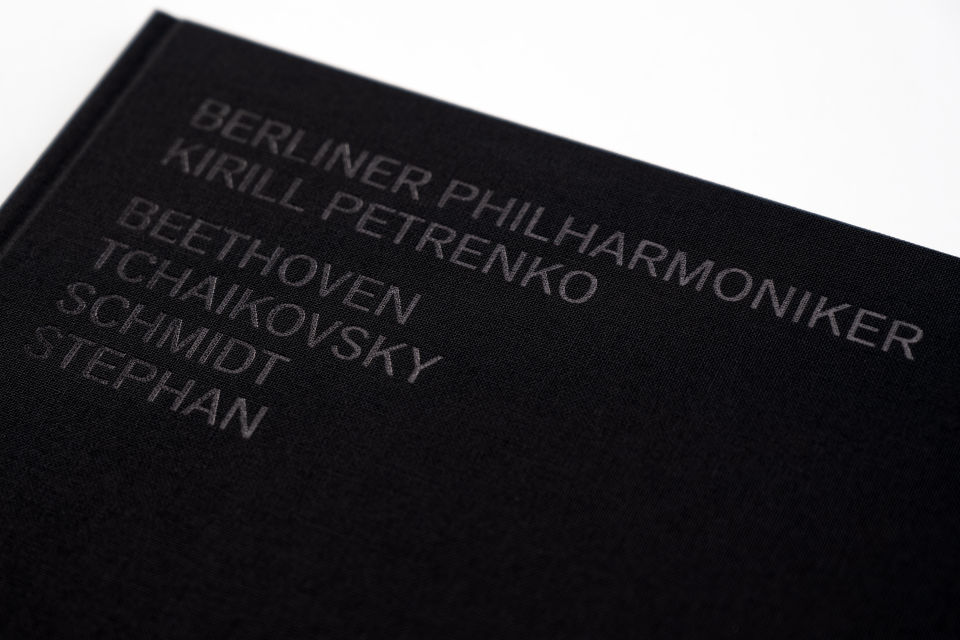

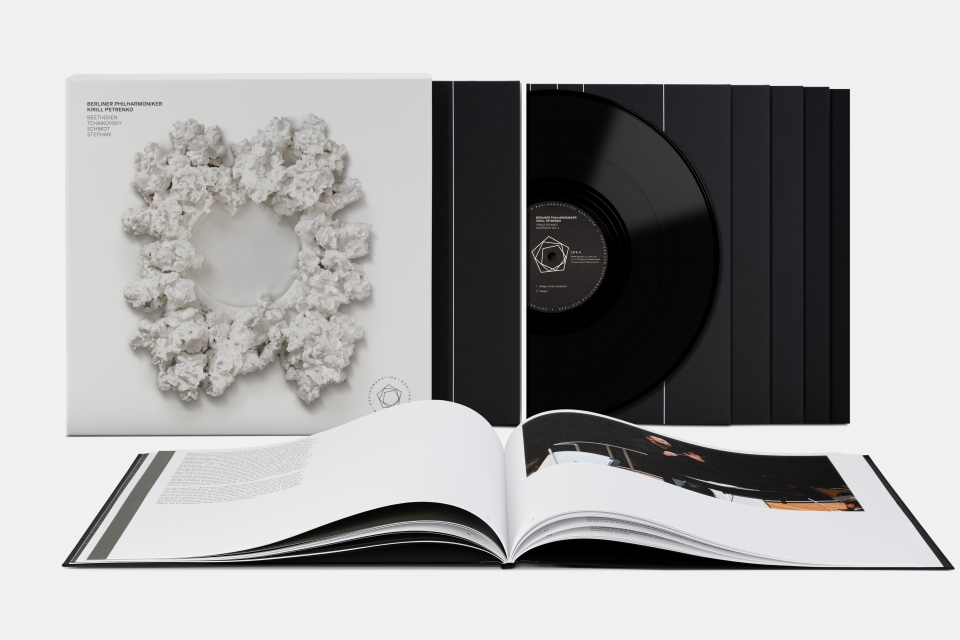

A Deluxe Vinyl Set celebrates the Beginning of the Kirill Petrenko partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

The Berlin Philharmonie, Home to the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

The Berlin Philharmonie, Home to the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Any notion that the classical music world is one of gentility, old world good manners and business discretion flies out the window when the position of new Principal Conductor or Music Director for one of the world’s top orchestras becomes vacant. And of all these orchestras (the London Symphony Orchestra, the Concertgebouw Amsterdam, the New York Philharmonic, the Chicago Symphony, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Boston Symphony - to name but a few), it’s the storied Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra which remains the greatest prize of all. (Its neighbour of equal high standing, the Vienna Philharmonic, does not appoint a Music Director, only engaging “guest conductors” for each series of concerts).

The Berlin Philharmonic is a self-governing body, run by the musicians themselves, who decide who will be their Artistic Directors/Chief Conductors.

From the beginning the orchestra enjoyed a starry line-up of Chief and Guest conductors, starting with the fabled Hans von Bulow (who conducted the premier of Wagner’s “Ring” cycle at Bayreuth in 1876).

Hans von Bulow

Hans von Bulow

Guest conductors included Hans Richter, Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler. In 1895 Arthur Nikisch took up the baton, and was succeeded by the legendary Wilhelm Furtwängler in 1923.

Wilhelm Furtwängler in 1925

Wilhelm Furtwängler in 1925

Furtwängler’s tenure at the helm encompassed the orchestra’s controversial role during World War II and its association with the Nazi Party, a subject I covered at length in my review articles of the Wartime Radio Recordings, released - like this set - by the BPO’s in-house label.

Like it or not, the fact is that it is name conductors who sell recordings, not orchestras (although the high profile of the BPO means it is one of the few with a brand strong enough to stand out in the marketplace). Therefore, deciding which conductor is going to have the headline on your brand is very important when considering the financial well-being of the orchestra.

The most familiar to classical vinyl collectors of the BPO’s post-War Chief Conductors is Herbert von Karajan (1954-1989) by virtue of his dominance of the classical record market over some four plus decades. His successor, Claudio Abbado (1989 - 2002) was similarly a major figure during the waning days of the classical boom in recordings. Simon Rattle (2002-2015) also came to the job with a well-established profile in the classical market, and under his leadership there was an expansion by the orchestra in its media outreach through the establishment of its own record label and streaming service, the Digital Concert Hall.

When Sir Simon Rattle decided, in 2015, to step down in 2018, there was a feeding frenzy in the classical world. A number of names were bandied around, including Daniel Barenboim, Christian Thielemann, Riccardo Chailly, Andris Nelsons, Gustavo Dudamel. At their first conclave to pick a successor to Rattle in May 2015 (no cell phones allowed) the orchestra failed to agree on one name. The following month they settled on then 43-year old Kirill Petrenko, General Music Director of the Bavarian State Opera.

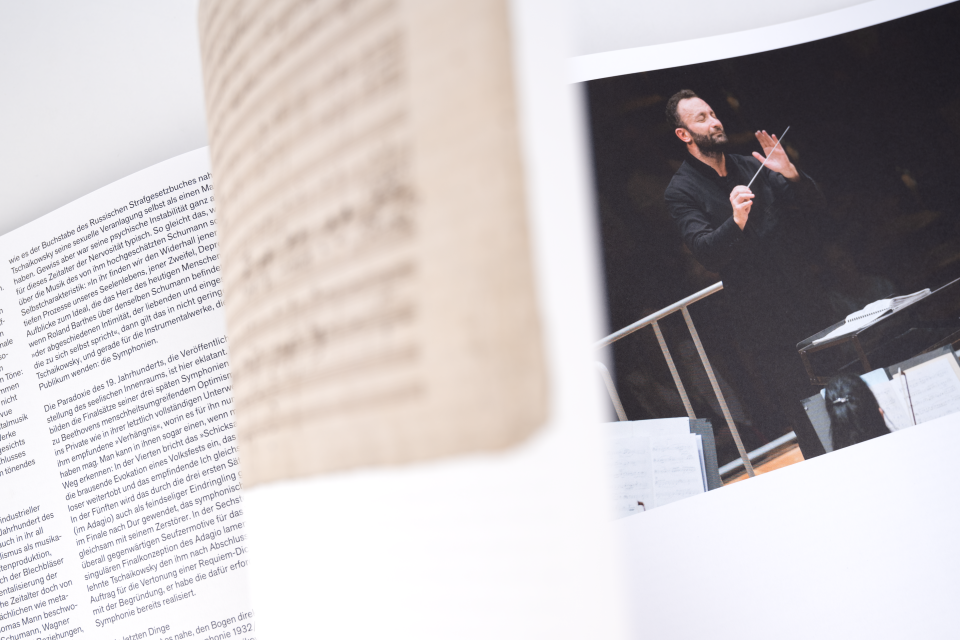

Kirill Petrenko

Kirill Petrenko

It was a surprising choice, especially considering the commercial considerations of attracting a name-conductor to the BPO brand. Petrenko (no relation to Vasily Petrenko who at the time was best known for his work with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic) was little known before his appointment, but that quickly changed. Classical enthusiasts sought out his few recordings, which included an outstanding set of Josef Suk’s major orchestral works on CPO.

As if recognizing the need to establish their new Chief Conductor’s recording credentials, in 2017 the BPO released a one-off recording of Tchaikovsky’s popular 6th Symphony, the Pathétique, first on a dual-layer CD/SACD, then on limited edition vinyl. It’s a superb recording on every level, establishing a new modern benchmark for the work. It boded well for the partnership.

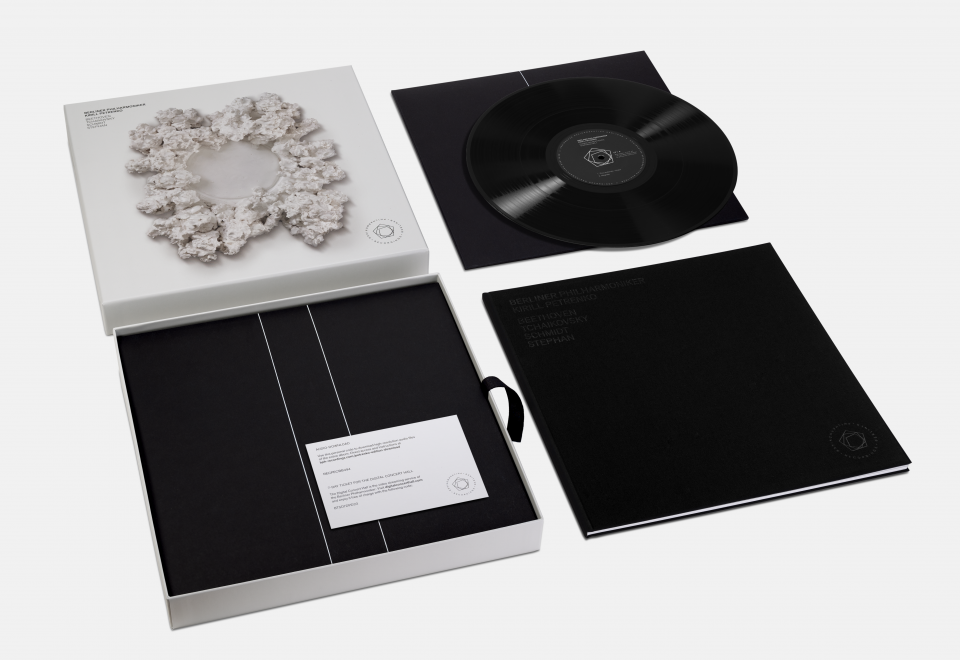

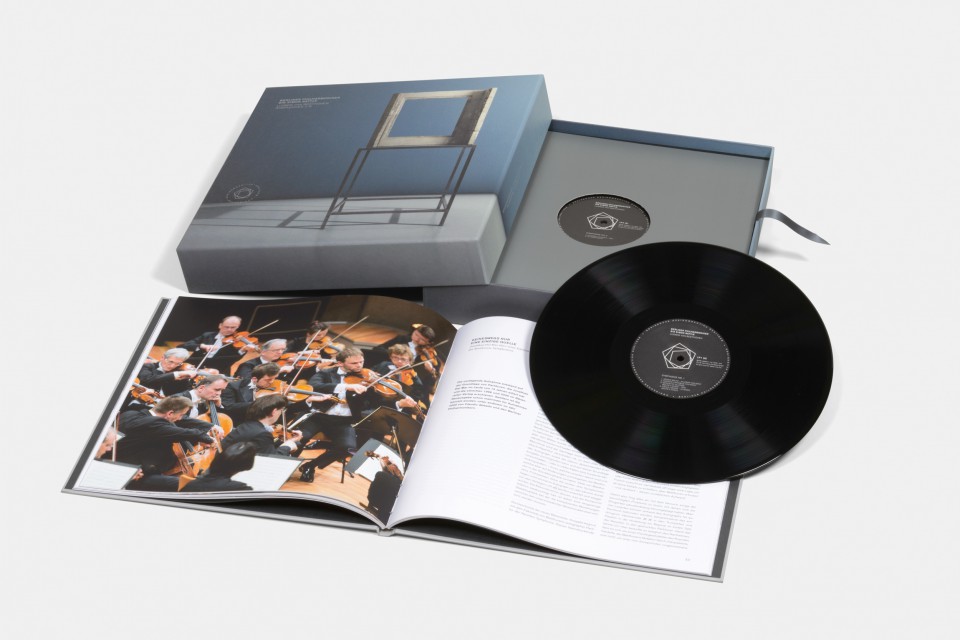

That Tchaikovsky 6th is included in this special numbered and limited to 1500 copies vinyl edition of recordings emanating from the early days of the Petrenko/BPO partnership, which was first released on CD and Blu-ray in the BPO’s customary bespoke box, more a rectangle than a traditional square CD sized box.

This vinyl edition comes in a traditional 12” vinyl-sized, lift-top box, sharing the same exquisite design elements as the CD box, plus the usual extensive accompanying book (reformatted to 12”), with first-rate essays and complete recording information.

All the recordings of that original CD box are included here - it is not a “best of” selection as was the case with the Furtwängler box. The 180gram platters are pressed at Pallas and my review copies of the LPs alone had no pressing faults. The whole package, as with all the BPO label releases, smacks of luxury, with careful thought being put into every design element. These are the Rolls-Royce editions amongst new classical vinyl box sets, as befits the top-flight quality of the performances contained within. I own quite a few of these BPO boxes - both vinyl and CD/SACD - and am very happy I do.

All the recordings in this set are taken from live performances given in the orchestra’s own fabled Philharmonie Hall, a stunning building in the center of the city, close to what used to be the Berlin Wall. In its day it was a groundbreaking design by architect Hans Scharoun, an early example of a concert hall moving on from the usual “shoe-box” design (typified by Boston’s Symphony Hall and Vienna’s Musikverein) towards a more “democratic” (ie. everyone, no matter where they sit, is closer to the orchestra), “in-the-round” design now emulated the world over (most spectacularly by Los Angeles’ Walt Disney Hall).

Berlin Philharmonie (left) and Disney Concert Hall (right)

Berlin Philharmonie (left) and Disney Concert Hall (right)

The Philharmonie opened in 1963, and was not without its acoustical challenges - most evident in Karajan’s early recordings made there - which have since been addressed.

Interior of the Berlin Philharmonie Main Hall

Interior of the Berlin Philharmonie Main Hall

These are all digital recordings made under the eagle ears of Producer Christoph Franke and Sound Engineer René Möller, who also share mixing and mastering duties. This team has long since tamed any eccentricities inherent in the Philharmonie’s acoustics. These are highly polished productions which serve the excellent performances well, though the question of whether digital perfection (and the orchestra’s own tendency towards an overtly polished and plush sonority) leads to a certain lack of organic analogue depth and texture to the sound did rear its head a few times during my listening. More on this later. This is not any kind of serious caveat, but it is something worth talking about on a sound-obsessed site such as this.

One of the attractions of this set is the blend of familiar and unfamiliar repertoire - and by unfamiliar I mean very unfamiliar. As is made clear in a somewhat heavy-handed essay by Armin Nassehi in the accompanying book (“Music in its Most Extreme Form - A sociological perspective on the symphony”), the works gathered here offer differing approaches to the symphony starting with the incipient Romanticism of Beethoven’s 7th (1812) and proceeding as far as the modern, though still tonal, 4th Symphony of Franz Schmidt from 1933, by way of Rudi Stephan’s Music for Orchestra from 1912. Stephan is a composer I’d never even heard of, and this work is a real discovery.

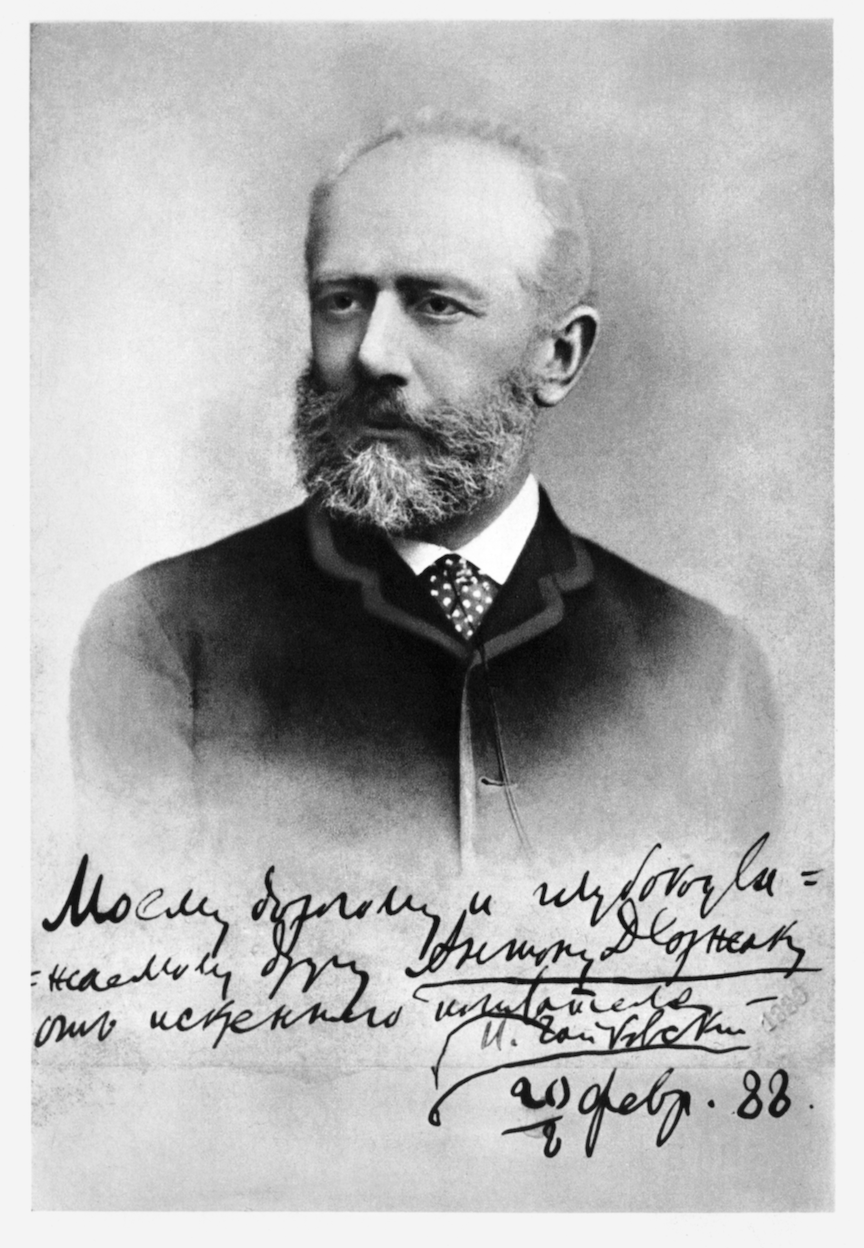

Peter Tchaikovsky

Peter Tchaikovsky

To the familiar first. I’ve already mentioned Tchaikovsky’s 6th Symphony. This is a tight, thrilling reading, full of all the sharp emotional contrasts required to make the piece work. This is not a work that performers can approach with any degree of reticence, and neither conductor nor orchestra do so here. Popular myth would have it that the “Pathétique” represents the composer’s musical confession of his inner emotional turmoil, his discomfort with his homosexuality, his anguish at his perceived failures both professional and personal. Premiered just days before his death, Tchaikovsky’s final symphony, which he described as being “saturated with subjective feeling”, represents a final fist shaking at overwhelming Fate (whose motifs had so dominated his last three symphonies), and a final surrender to it - spelled out in heart-rending detail in the work’s final acquiescent and despairing movement.

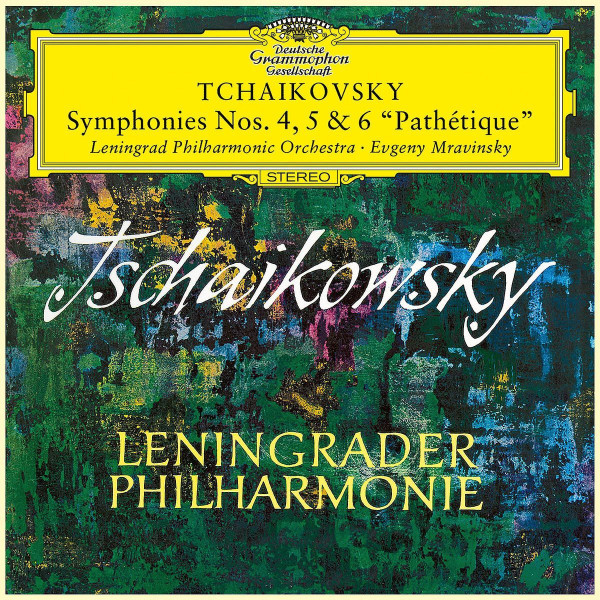

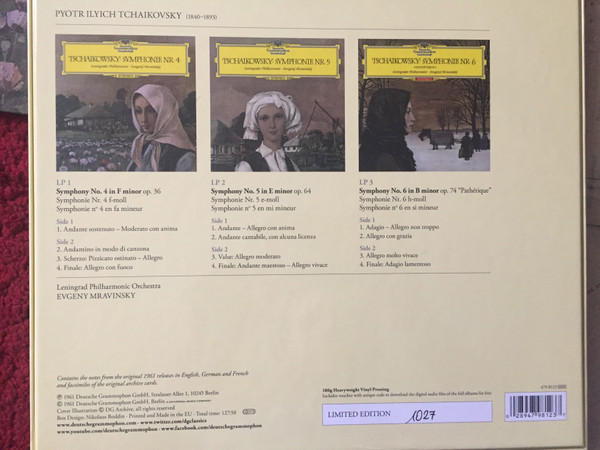

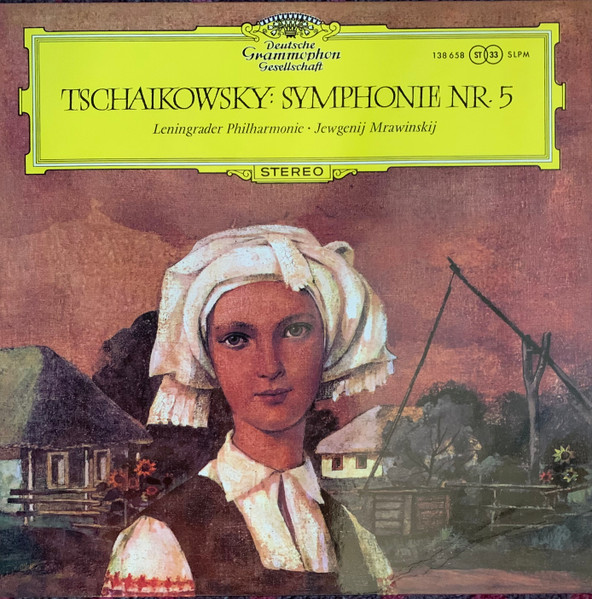

Everyone will already have their own favorite versions of this work. Certainly no lover of the last three symphonies should be without Yevgeny Mravinsky’s legendary accounts with the Leningrad Philharmonic, recorded for once in excellent sound by Decca engineers for Deutsche Grammophon while the orchestra was on tour in London. If you can find a copy of Rainer Maillard’s all-analog cut for Analogphonic, also reissued by DG, you will be in “Tchaikovsky Done Right by the Russians” heaven!

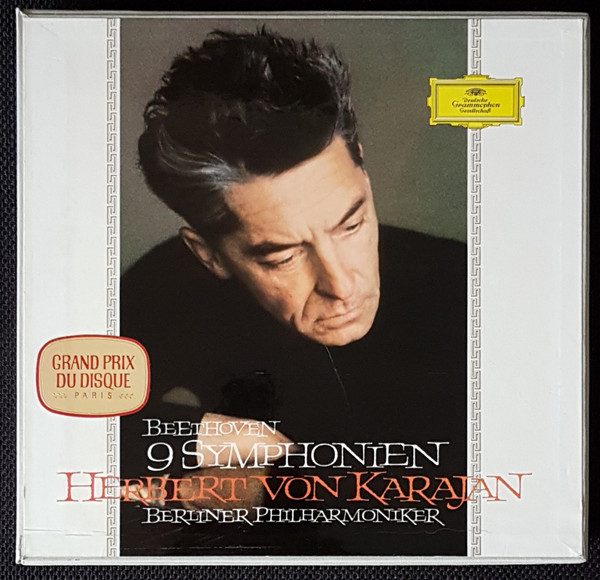

Karajan recorded the symphony at least three times with the Berliners, and they’re all very good recordings. For the best combination of sound and performance I’d either go for a “large-tulips” pressing of the 1964 DG, or the EBS remastered single layer SACD set of all six symphonies recorded in the 1970s.

However, for what might be the ultimate vintage vinyl experience of this work, I will opt for my King Super Analogue reissue of Jean Martinon’s recording with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. Even my exceptional Decca wide-brand pressing of this searing performance cannot match the pristine sonics and pressing of the King/Cisco reissue, one of the prizes of my collection (and a record that ended up being in my pile of potential vinyl evacuees last week in LA).

Original Decca Pressing

Original Decca Pressing

But Petrenko and the Berliners in this set can withstand comparison to any of these. It’s no wonder that the BPO label rushed this one out as a standalone release as quickly as they did.

Music: 10

Sound: 9

If the Tchaikovsky 5th doesn’t quite scale the heights of the 6th, it is nevertheless no slouch. This is again a wonderfully characterful performance of my favorite amongst Tchaikovsky’s Big 3. (I also love the 1st “Winter Daydreams” and, lo and behold, as I type this my review copy of Michael Tilson Thomas’s recording with the Boston Symphony on DG’s Original Source Series has plopped onto my doorstep. Maybe audition tonight…)

This is a terrific Tchaikovsky 5th, though again it must cede top recommendation to Mravinsky’s rendering in London with the Leningraders on DG.

Here I might slightly favor the Speaker’s Corner pressing of just this symphony, which, unlike the boxed EBS remastering which goes with the OG artwork, here features the gorgeous LP artwork of the first DG repressing. (It is simply tragic that all those Speaker’s Corner pressings of classical are now essentially OOP - they were the best way for classical collectors on a budget to get many impossible-to-buy releases in often sonically improved editions).

Music: 9

Sound: 9

Two other classical warhorses feature in this box, Beethoven’s 7th and 9th Symphonies.

Do we really need yet more new recordings of these two works, I hear even the more casual collector sigh? Well no, not really. But I guess the new guy in Berlin felt a need to put down his marker in this repertoire (and the label felt it would be a draw).

Of the two, I find the 7th more successful, benefitting from Petrenko’s no-nonsense approach, suffused with his characteristically well sprung rhythmic control by which this work lives or dies.

But here I was starting to be bothered somewhat by what I will describe as the well-rendered, utterly controlled, corporate digital sonics I was hearing. Let me be clear: there is nothing “wrong” with the sound. Everything is in its place and presented clearly, with a nice sense of the hall. This is the BPO sound - lush, virtuosic. In fact, this is as good an example as you are likely to hear today of any orchestra recorded “live”. And that is the problem.

Orchestras today are all sounding the same - or at least the recordings of them are all sounding the same. All multi-miked for optimal editing options in post-production.

To get some sense of what I was missing I turned to the same symphony, Beethoven’s 7th, recorded in the same hall with the same orchestra for the same label by its previous Chief Conductor, Simon Rattle, as part of his complete cycle first released on CD/Blu-ray in 2016. In 2017 this was released in a limited edition vinyl box.

But, unlike other vinyl editions on the BPO label, this set was not sourced from the same masters as the CD/SACD release. The vinyl edition was derived from (still digital) recordings made from a different microphone set up, essentially a modern variation of the Decca Tree. According to recording producer Christoph Franke:

“A Sennheiser MKH 30 microphone (figure-8 pattern) was combined with a Sennheiser MKH-20 microphone. After several trials, the M/S pair was placed in the approximately one cubic meter area where almost all main microphones from different recording teams are positioned: roughly above the first row of seats in Block A, at about 5.20 m height above the stage in the center. This is approximately the same position we used for the Brahms Direct-to-Disc recording. Acoustically, this is the area of the critical distance, where there is an ideal balance between direct and diffuse sound. In the Philharmonie Berlin, due to the room geometry, the critical distance is surprisingly large, allowing for a very clear and present signal even at greater distances. In other halls, at this position, you would only get a very unclear sound image”.

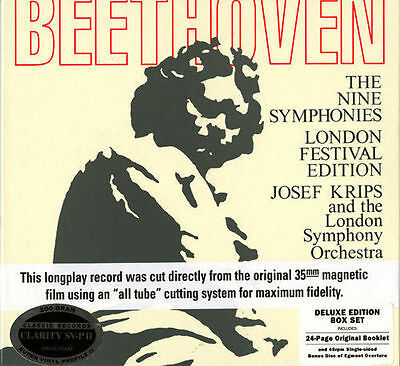

The sonic difference is very noticeable, with the Rattle version affording a more organic, three-dimensional orchestral picture that has been painted in real-time rather than manipulated into existence in post. This whole set, albeit digitally recorded, sounds marvelous. What a difference that “purist” miking makes. Wanting to dive deeper into sonic alternatives I dug out my Classic Records AAA reissue of the complete Everest Josef Krips/LSO Beethoven cycle, originally recorded to 35mm film.

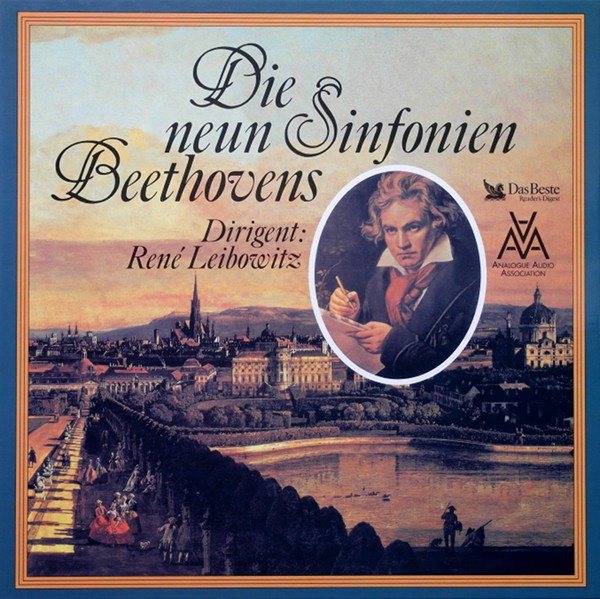

This is about as purist an audiophile analogue recording as it gets and, if you can live with Krips’s old-fashioned approach to Ludwig van (and I certainly can), then just prepare to sink into an organic, all-enveloping sound that acts like a time machine, transporting you right back into Walthamstow’s Assembly Hall in 1959, courtesy of Bert Whyte and his engineering team. Pressed on Clarity vinyl, this reissue was released during Classic’s sunset years when its pressings were rarely free of tics and pops and other irregularities, but who cares. After a good cleaning these recordings have a vividness and organic quality matched by few. (One would be the Rene Leibowitz Beethoven cycle with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, recorded in the same hall for Reader’s Digest in 1962, supervised by soon-to-be-legendary Charles Gerhardt; given a deluxe AAA reissue by Edition Phönix in 1993).

Speaking of 3-dimensional, shall we just mention the recent Original Source Series reissue of Carlos Kleiber’s magnificent rendition of the 7th with the Vienna Phil recorded in the Musikverein - one of the best in this whole reissue series, which is saying something.

Music: 9

Sound: 8

Turning to the 9th I tried to keep an open mind - I wanted to be thrilled, as one always does when one listens to a new version of this ultimate classical warhorse. Well, as is usually the case, I was underwhelmed. This simply is an almost impossible work to get right both performance-wise and sonically.

Again, don’t get me wrong - this a perfectly respectable outing, and better than many. But be warned, it is thoroughly in the mold of modern 9ths - ie. even though not performed on period instruments, it just as well could be in terms of how it is put together. Tempi are swift: there is no dilly-dallying - a blessing in the often interminable and sagging slow movement which is almost impossible to nail, but a big minus when it comes to communicating the gravitas of the first movement and the heaven-storming proclivities of the final movement with its ecstatic chorus and soloists proclaiming a new Utopian “Ode to Joy”. (Beethoven’s idealism that served as a beacon of hope through two world wars and the fall of the Soviet Union is feeling especially out of tune with the world’s current trajectory - maybe that’s why today we are getting so many workmanlike, almost perfunctory, recordings of this symphony).

After an alert opening movement that gets nothing wrong but misses the epic, I like how Petrenko rocks the brilliant second movement, one of Beethoven’s most thrilling roller-coaster rides (though Petrenko still falls behind my personal favorite here, Erich Leinsdorf with the Boston Symphony in 1969), with a lovely rendering of the Trio section. Here the sublime contrapuntal lines are given all the love that the Berliners can give, the horns toll the bell in a sunset bathed in a golden glow, and it will all melt your hardened heart before that infectious Scherzo kicks off its addictive ride once more.

The opening Recitative-like section of the final movement, in which melodic call-backs to the earlier movements are introduced and dismissed, is not unsurprisingly well handled by Petrenko the well-seasoned opera conductor. But a desire to keep things moving, to comply with current notions of Historically Informed Performance practice (notably in matters of Beethoven’s controversial metronome markings) robs this opening of its portent, its weight, and this extends to the whole choral finale which feels more workmanlike than divinely inspired. And then we have the perennial problem of the soloists which confronts every recording of this work from time immemorial. There’s always going to be a weak link, and it’s usually the soprano whose part is - to put it simply - impossible. Beethoven wrote for voices as if they were instruments, with little heed paid to matters of vocal mechanics and how voices actually work. Beethoven just wants his singers to hit all the notes, however madly written they might be. The soprano has to sound effortless, floating gloriously, serenely above the fray. For Petrenko, poor Marlis Petersen hits the notes, but her tone is thin rather than rich, and you can hear her working very hard.

The choir is well drilled, but they often fall prey (as do the soloists) to hitting all the notes in the phrases equally (a problem in Beethoven’s choral music), without giving us a flowing musical line. It keeps the music firmly anchored on the ground when it should be flying towards the heavens.

Thus, with Petrenko rarely taking pause, the movement lacks the necessary sense of aspiration and ascendancy towards the utopian ideal. It hurtles towards its loud and busy conclusion like a sleek, modern bullet train - all chrome and no heart. And little transcendence.

I am sure there will be many who do not share this opinion. Those who are fully onboard with the new objectivism in Beethoven will applaud the vitality and virtuosity of Petrenko’s rendition, and will forgive the vocal shortcomings - and for them and many others this recording will be more than adequate.

However, if I’m going to sit though the 9th in my listening room, or the concert hall, I demand more - and I have only found it once in both situations.

In the concert hall, the 9th that will forever reign in my heart and soul will be - from all people - Simon Rattle - so often underwhelming on record - but here with the Berliners, back in London at the Proms in 2004 in the mid-noughts, on top form. It was truly epic, transcendent, and the audience roared its approval to the heavens with a fervor that would have pierced Beethoven’s deafness, if, perchance, he was eavesdropping from above.

Simon Rattle and the Berliners at the BBC Proms in 2012, with the grand Royal Albert Hall organ visible behind

Simon Rattle and the Berliners at the BBC Proms in 2012, with the grand Royal Albert Hall organ visible behind

On record, there remains - after years of seeking out alternatives - only ONE version for this listener: Karajan’s 1962/3 rendering with the Berlin Philharmonic and the Vienna Singverein, plus the best quartet of soloists ever, headed by the effortless, majestic, glorious soprano of the otherworldly Gundula Janowitz - floating above the stave as if she was in the presence of the Almighty himself (she was - after all it is Karajan conducting…!!!) One may quibble with elements of the other movements (and prefer aspects of these in his 1977 version), but the choral finale, the “Ode to Joy”, is elemental in all the right places. Every time I listen to another recording I just wish I was listening to this one. Seek out a “large tulips” pressing of this coupled with the 8th, or of the whole set, or - if you can find it - the Speaker’s Corner all-analogue reissue of the complete 1963 cycle.

Rattle, in his live 2016 cycle with the Berliners referred to earlier, is very good indeed, and the sound is striking in how it differs from what we hear for Petrenko. There is a greater sense of the depth and height of the Berlin Philharmonie, a fact that strikes with full force with the first entrance of the solo bass, Dmitry Ivashchenko, as he declares his celebrated invocation:

“O friends, no more these sounds! Let us sing more cheerful songs, more full of joy!”

Standing at the back of the orchestra, in front of the choir, his voice reverberates around the hall: it’s almost too reverberant, but the point is that it is that very expansiveness which makes the voice sound more real, versus the carefully controlled sound on the Petrenko version.

For the recording of this symphony, producer Christoph Franke supplement his main pair of microphones:

“Only for this symphony we had to use additional microphones as the choir and the soloists were positioned behind the orchestra. We used a total of 6 additional spot microphones: 4 for the choir (2 for each side) and 2 for the soloists. These additional microphones were blended in very subtly to not interfere with the main M/S recording”.

Throughout the Rattle version, there is more weight, richness but also an organic “messiness” to the sound - but it feels real, like an orchestra playing in the actual space. An analogy might be between a fine watercolor (Petrenko) and an old Master oil painting (Rattle): the contrasting but blending timbres of the different instruments and sections are drawn in deeper color. Also Rattle’s performance takes its time, not wallowing, but allowing for Beethoven’s music to fill the spaces between the notes. His Finale soloists are also superior, and the Choir phrases more musically and definitely has more body. The climax of the Finale is far more suitably overpowering. In the end, however, Rattle is still no Karajan - that 1962/3 version should be in every collection.

Music: 8

Sound: 8

So, with regard to the standard repertory items in this box, it’s a slightly mixed bag. Essential Tchaikovsky 6th, excellent Tchaikovsky 5th; Beethoven not so essential but nice to get a marker of Petrenko in this repertoire with a thoroughly engaging 7th, but a 9th that needs rethinking (especially in matters of tempo and being a little more parsimonious with those vibrato-less strings). State-of-the-art digital recordings with all that implies, but better in the Tchaikovsky than the Beethoven.

I have left the best ’til last, and for the remaining two works alone (plus the Tchaikovsky symphonies) this set is worth serious consideration.

Rudi Stephan

Rudi Stephan

Going by his Music for Orchestra, the world lost a significant musical voice when the composer Rudi Stephan was shot in 1915 at the age of 28 in World War I. He had only lasted two weeks on the front. At his farewell to his parents he had apparently said: “If only nothing happens to my head. There is still so much beauty in it.”

Studying at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt and later at the Munich Academy of Music, Stephan had already had concerts (financed by his father) dedicated to his music, and was beginning to establish his reputation when drafted. Unfortunately a vast trove of his manuscripts and unfinished works was destroyed by the Allied bombing of Worms in 1945.

I listened to this piece directly after Beethoven’s 9th, and it acquitted itself very well indeed. As the notes say:

“Music for Orchestra” has the intensity of a symphonic distillation. A handful of partly related ideas forms the thematic material from which Stephan creates, in brief, contrasting episodes, an organic and effectively scored sound cosmos. In the process he generates unity out of change, as manifested in the delicately lyrical solo violin melody that mutates into a forceful fugato theme.

This is instantly compelling music, and the Berliners play it with a degree of commitment that is noticeable - no doubt relieved to be tackling something other than another repertoire warhorse. The opening pedal point will instantly have you thinking you put on Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra by mistake! However we then move into a world that, while clearly influenced by the late-Romanticism of composers like Strauss, is also swimming into the heady currents of musical expressionism and pre-serialism. Stephan was also deeply influenced by Stravinsky. But already his own clear musical personality is emerging - and it’s an enticing one.

Interestingly, the sound is more open than on the Beethoven, and when the huge tam-tam hits it expands and fills the sonic space just like it should. There is bite, precision and warmth to the playing, and you will hear the stage and hall thrumming in sympathy to the lower regions of the orchestra. In all honesty, this may be my favorite piece in the set. How about Petrenko and the Berliners give us more Rudi Stephan?

Music: 9

Sound: 9

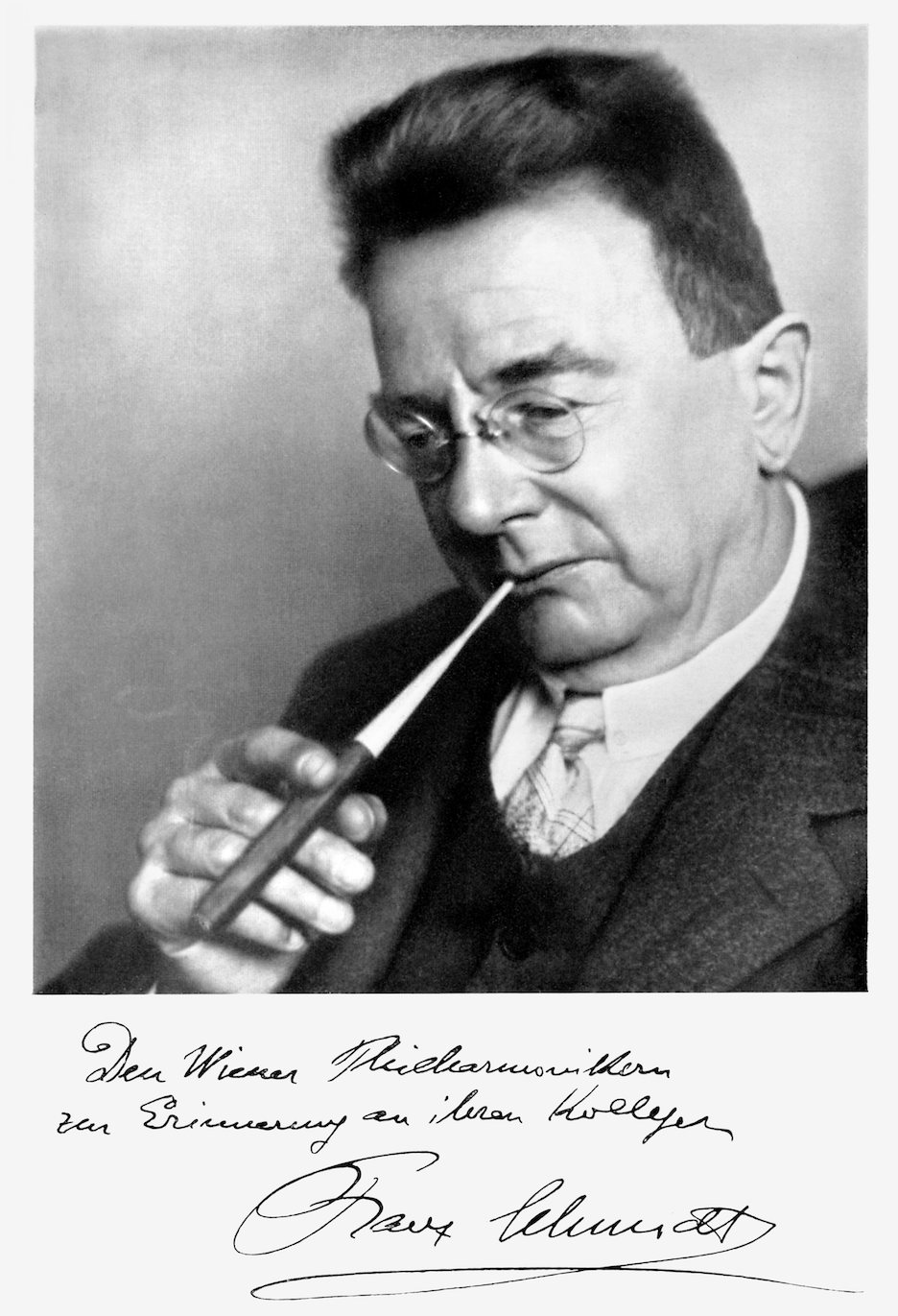

Franz Schmidt

Franz Schmidt

Likewise the performance of Franz Schmidt’s best known symphony, No. 4, is fresh and compelling. For years pretty much the only recording of this around was Zubin Mehta’s 1973 audiophile rendition with the Vienna Philharmonic on Decca, an essential purchase for any serious classical collector.

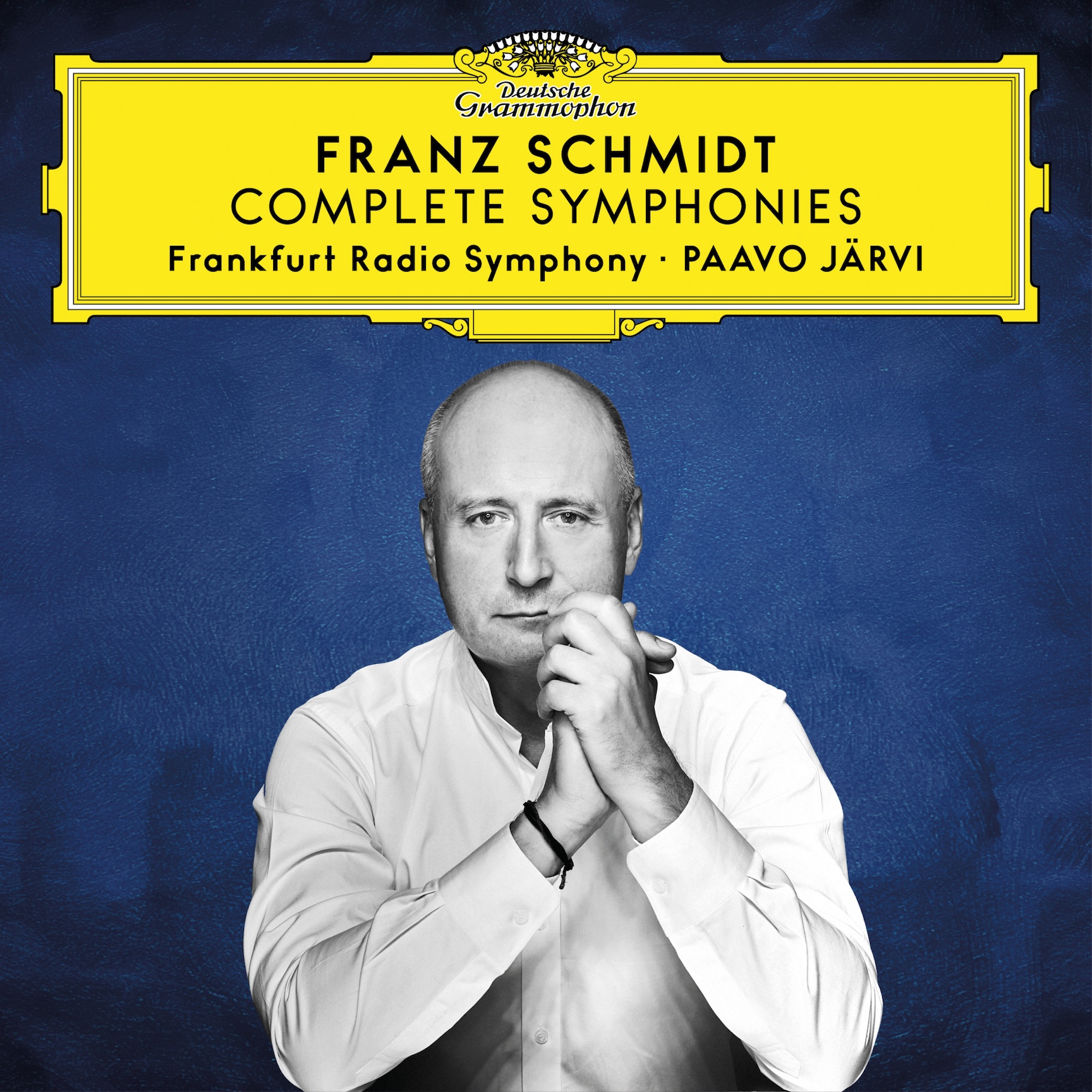

Of late, Schmidt has been getting a lot of attention, with a well received set of all his symphonies being released in 2020 by Deutsche Grammophon, with the ever enterprising Paavo Jarvi conducting the Frankfurt Radio Symphony. (To my shame I have yet to listen to it).

Franz Schmidt was a highly accomplished ‘cellist, playing under Gustav Mahler at the Vienna State Opera, and friendly with Arnold Schoenberg, and you can plainly hear the influence of both men in Schmidt’s music. (Schmidt played in the premiere of Verklärte Nacht, and you will hear many echoes of this and Gurrelieder in the 4th Symphony). He was also a fine pianist and became a renowned teacher at his alma mater - the Vienna Conservatory (which was renamed in 1909 as the Imperial Academy of Music and the Performing Arts). Schmidt belongs firmly in the symphonic tradition of Brahms and Bruckner - in fact a good way to think of this 4th Symphony is as an extension of Bruckner (with whom he studied counterpoint briefly). He remained a tonal composer in an age of harmonic disruption.

This is a symphony more or less oblivious to the aesthetic and philosophical eruptions that were consuming classical music at the time, and is none the worse for it. One of the positive side effects of classical music largely moving on from the dogmatic adherence to serialism, non-tonality and all the other paraphernalia of mid to late-20th century modernism is that works that fell outside the sphere of the self-appointed revolutionaries are finally entering the repertoire on a more regular basis. We are no longer making apologies for playing music that has tunes and traditional harmony!

The 4th Symphony opens with a solo, forlorn trumpet solo, immediately conjuring up echoes of “The Last Post” and the lone trumpet call that opens the Funeral March of Mahler’s 5th Symphony. This poignant, desolate trumpet passage ushers in a work the composer considered a Requiem for his 30-year old daughter who had recently died after giving birth. Its chromatic, meandering line, which provides material for the rest of the work, sounds like a lost melody clawing its way towards tonality and meaning. The solo trumpet returns at the end of the symphony, described by Schmidt as “a last music to take along into the next world.”

The dominant mood of the work is therefore sad and reflective, but there is also an underlying, poignant expression of love and tenderness, to the fore in the second half of the third movement which appears after an almost childlike scherzo. This ravishing love music for a lost child will bring a tear to your eye.

Petrenko and the Berliners are clearly fully invested in this exceptional example of mid-20th century symphonic writing. While they cannot dispel my allegiances to the fine Zubin Mehta rendering with the VPO (captured in characteristically rich, effulgent Decca sound - a record you should be able to find at a reasonable price in either of its 1972 Decca or “Made in England” London incarnations), this is a compelling modern recording. I must say that re-listening to the work for this review increased my admiration and love for it - it’s a hidden gem of the 20th century orchestral repertoire.

Music: 9

Sound: 9

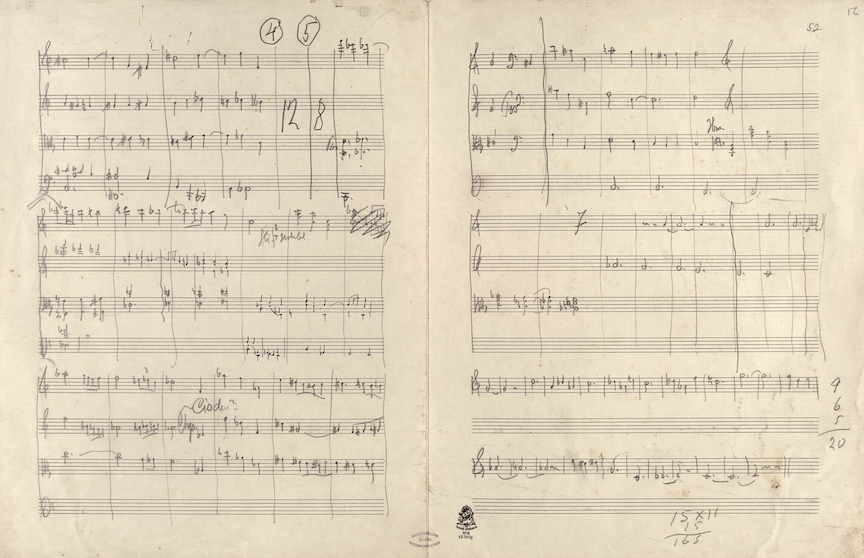

The last bars of Schmidt's autograph score for the 4th Symphony, with solo trumpet disappearing into the ether...

The last bars of Schmidt's autograph score for the 4th Symphony, with solo trumpet disappearing into the ether...

Which brings me to a dominant thought I had after listening to this fine set and its companion release by Petrenko and the Berliners of Shostakovich symphonies (reviewed here). While I can appreciate Petrenko’s allegiance to the core symphonic/orchestral repertoire that the Berliners know backwards, and his desire to establish his credentials in this music, I am more excited by his forays into less well-known territory. Yes, it’s great to hear him do Tchaikovsky so compellingly, especially given that composer’s long absence from BPO concert programs under Rattle, but what really fired me up as a listener were the Schmidt and Rudi Stephan works in this set, and the three Shostakovich symphonies in that CD-only box. I have yet to hear the Petrenko/BPO box of Rachmaninov, but how exciting would it be to hear complete Shostakovich and Prokofiev symphony cycles, plus the latter’s Romeo and Juliet and Cinderella ballets. Throw in a Tchaikovsky cycle for good measure. How about some Schoenberg, Berg and Webern; Stravinsky, Bartok, and minimalists like Steve Reich and John Adams (Petrenko’s fine account of The Wound Dresser was included in the BPO’s mandatory John Adams set). Hindemith, Britten, Ravel and Debussy perhaps?

Whatever the future may hold, this set clearly demonstrates the partnership between one of the world’s finest orchestras and a fresh new conductor on the world stage is off to a great start, and if you prioritize superior sound and the vinyl experience this limited edition vinyl set is the best way to experience these recordings. (You, will, however, be missing out on the filmed concerts and video features from the CD/Blu-ray incarnation).

It’s also a great set for someone just getting into classical vinyl, with a nice array of core repertoire and unusual works, all in performances that range from top notch to excellent. Others may respond to Petrenko’s 9th more positively than I did. It certainly has many virtues even if it ultimately fails to stick the landing - but that’s how I would describe 99% of Beethoven 9ths on record!

The digital sound represents the best version of what you are going to hear on most orchestral recordings these days. That it lacks the personality of the best of older recordings is merely a reflection of where we are currently with the technology and approach to capturing live performances. It’s part of the sacrifice made to have more flexibility for ironing out defects in post-production. Turn to the Rattle/BPO Beethoven cycle in its minimally-miked vinyl incarnation for a more vibrant, three dimensional sound, or better still the D2D Haitink Bruckner 7th, which will cost you an arm and a leg, but will place you firmly in the Berlin Philharmonie at the conductor’s elbow.

Moving forward, it would be great to see the BPO label embrace these older-school technological approaches to capture the orchestra’s fabled sound more organically. After all, this is an orchestra renowned for its playing precision, so I think they could afford to live a little more dangerously to achieve a more distinctive - and exciting - sonic result. Or at least if planning a vinyl release, record both ways as the label did for the Beethoven Rattle set: minimal miking for the vinyl, multi-miking for CD and blu-ray.

And how about doing the occasional Direct-to-Disc special limited edition release, as the BPO has done before with the Bruckner and the Rattle Brahms Symphony cycle? The “highly-experienced-in-all-things-D2D” Emil Berliner Studios are - after all - just down the street…

That way collectors and fans of the orchestra would not only be celebrating this orchestra’s latest musical partnerships in these excellent BPO label releases, but doing so in sonics that did fuller justice to the orchestra’s rightly celebrated virtuosity and sound.

Recordings made between 2012 and 2019 at the Philharmonie Berlin.

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Kirill Petrenko

Marlis Petersen (soprano); Elisabeth Kulman (mezzo-soprano); Benjamin Bruns (tenor); Kwangchul Yuon (bass)

Rundfunkchor Berlin

Audio Production Recording producer: Christoph Franke

Sound Engineer: René Möller

Editing: Christoph Franke, Alexander Feucht

Mixing and mastering engineers: René Möller, Christoph Franke

Vinyl Mastering: Sidney C. Meyer, Emil Berliner Studios

Artwork: Rosemarie Trockel

Executive Producer: Olaf Maninger

Project Managers: Felix Faustel, Timo Hagemeister

Six 180 gram LP set

1,500 copies, limited edition

Clothbound hardcover book, 56 pages

Includes card with download code for audio files of the complete edition in 24bit and up to 192kHz

Available for purchase directly from Berlin Philharmonic Recordings. It's also worth hunting around other specialty retailers like Presto Music in the UK; Acoustic Sounds, Elusive Disc in the US, who often have competitive pricing in your region.