Sonny Rollins' L.A. Adventures

East Coast Master Meets West Coast Jazz, 1957-58

In March 1957, Sonny Rollins was 26 and one of the hot young tenor saxophone players (matched only by his friend John Coltrane) when he went out to L.A. with the Max Roach quartet and, one night, in his off hours, stepped into a warehouse that doubled as a studio for Contemporary Records and laid down the tracks of Way Out West. (I mean “off hours” literally; the only time he and his bandmates could get together, in between club gigs and other recording sessions, was 3:00 AM. They finished plowing through several takes of a half-dozen songs at 7:30 AM.)

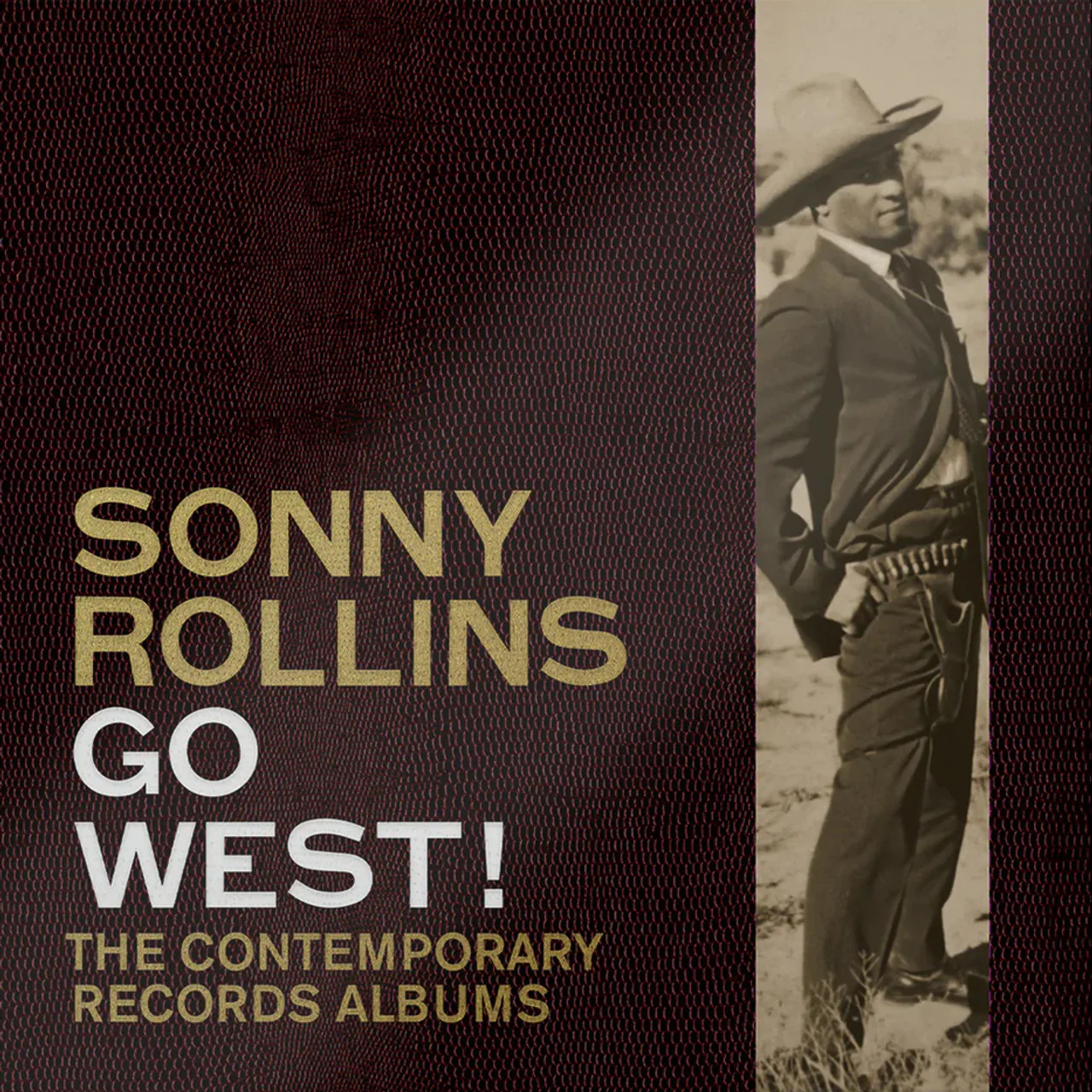

The album—remarkably energetic, under the circumstances—was seen as oddly innovative at the time, and not just for the cover photo of Rollins getting deep into the spirit of the title, decked out in a cowboy hat, holster, and six-shooter. Almost as striking was the ensemble: a piano-less trio—a free-spirited experiment out of whack with the reining be-bop style, which was built on chords, which were usually supplied by a pianist. This session featured just Rollins on tenor sax, bassist Ray Brown (who happened to be in town with Oscar Peterson), and drummer Shelly Manne (a local and a Contemporary staple). Rollins was hitting new peaks as a stellar soloist—he’d led seven recording sessions in the previous year (including Tenor Madness, which included a 12-minute track sharing the frontline with Coltrane, and Saxophone Colossus, which carved Rollins’ identity as an improviser), and he welcomed the freedom of not being tethered to chord progressions. Six months later, he pushed further out still along this marker-less road on the live album A Night at the Village Vanguard with Wilbur Ware and Elvin Jones.

(A parenthetical note. You could compare Way Out West with A Night at the Village Vanguard as a contrast between East Coast and West Coast jazz. The latter was more spacious, a bit softer and cooler; the former faster and harder-edged. The concept—which was a PR invention—is sometimes exaggerated, but there is a there there. Check it out.)

Craft Recordings has a new three-LP boxed set called Go West!, which contains remasters of Way Out West, Sonny Rollins & the Contemporary Leaders (a follow-up L.A. album that he made for the label a year-and-a-half later), and Contemporary Alternate Takes (outtakes from both albums first released in the mid-1980s).

Way Out West is a long-esteemed classic. It may be most famous (and instantly recognizable) for the opening track, Johnny Mercer’s “I’m an Old Cowhand,” with Shelly Manne’s hip horse-hoof intro (which he cannily created using a wood block, snare rim, and bass drum), but that shouldn’t sum the album up. It sports some of Rollins’ most graceful solos on standards (“Solitude,” “There Is No Greater Love”), originals (“Come, Gone” and the title tune) as well as a novelty (“Wagon Wheels,” which, aside from Rollins’ soloing, is unfortunate). The interplay is lively and inventive; it’s remarkable that Rollins and Brown never played together again.

Contemporary Leaders is a different matter. It also featured a one-off band, but larger: Manne again on drums, this time with pianist Hampton Hawes, guitarist Barney Kessel, bassist Leroy Vinnegar, and, on one track, Victor Feldman playing vibes—all regular musicians for Contemporary. (Ornette Coleman was recording his first album for the label around this time; he and Rollins got to know each other, even played sax together on the beach. It’s a shame that he couldn’t have joined them on at least one track.) Rollins is a riveting pleasure as always, the band is proficient, but it’s a largely uninspired album. Many of the songs are cheesy (“Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody,” “I’ve Found a New Baby”), though there’s a breathtakingly fast take of “The Song Is You.”

Alternate Takes has its moments, but you can tell these are alternate takes. Most interesting is an early rendition of “I’m an Old Cowhand” that’s nearly twice as long as the master take (10:06 vs. 5:42), and it’s fascinating to follow, but you can tell Rollins is groping for a steady path and a way out. He doesn’t really find one. For completists only.

Back in 2018, Craft put out a vinyl boxed set of Way Out West and Contemporary Leaders, but as Michael Fremer complained at the time, it was mastered from digital files (even though the analog tapes were in fine condition) and the engineer handling them failed to turn down the high frequencies, as the session’s notes instructed. Contemporary’s engineer, Roy DuNann (who was as great as Blue Note’s more renown Rudy Van Gelder), sometimes recorded with the high frequencies turned up. Then, when mastering, he would turn them down—and, as a result, eliminate tape hiss. (It was his own, unelectronic, pre-Dolby version of Noise Reduction.) Some of the early reissues didn’t follow DuNann’s directions, and the results sounded too bright. The lesson had been learned long before Craft’s 2018 boxed set, but I guess some hadn’t read the memo.

This time out, Craft went back to the original analog tapes and, for mastering, hired Bernie Grundman, who knew all about the DuNann HF adjustment. As with the originals, Way Out West has Rollins in the left channel, Brown and Manne in the right. (This was 1957 stereo.) Contemporary Leaders spreads the quintet (on one track, sextet) across the soundstage. In both cases, the sound quality is very good. I compared Way Out West with an original pressing (on the Stereo label, which is how Contemporary Records marked its stereo albums until the RIAA told the owner, Lester Koenig, that he couldn’t do that) and with a reissue put out a few years ago by the Electric Recording Company. The new Craft is a notch below both: the snare drum and cymbals aren’t quite as crisp, and there’s not quite as much air surrounding them; you don’t hear quite as much snap in Ray Brown’s fingers. I wonder if, while adjusting the high frequencies, Grundman might have turned them down a little bit too much. Still, these are minor critiques. The new Craft comes impressively close to the original and the ERC—which, in any case, are both out of print, very hard to find, and very expensive if you do. Rollins’ horn is as husky, present and resonant as it should be, and that’s the important thing.

The box is handsome, and it includes a booklet with photos and an informative essay by Ashley Kahn as well as an entertaining interview that he conducted with Rollins.