Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra (updated with comments from producer/annotator Charles Granata)

A Neglected Album is finally restored to its rightful place as one of Sinatra's masterpieces.

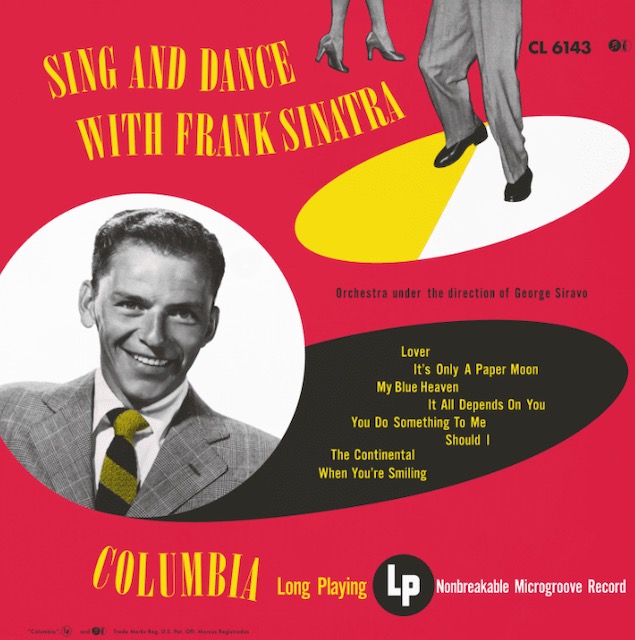

Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra

and the Birth of the Concept Album

Introduction

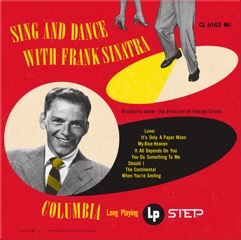

This new 45-rpm, 2-LP 1step version of Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra is the second time Impex Records has remastered this album for the audiophile market. The first, in 2020, was also 2-LP but pressed at 33⅓ without the 1step process and some other improvements I shall detail later. Recorded between April and October of 1950 and released that same month, Sing and Dance is the sixth and last album Sinatra made for Columbia Records. Seven songs were recorded specifically for the album, one shy of the eight typically needed for a 10-inch LP of popular music. So an eighth, “It All Depends on You,” drawn from a session in July the previous year, was added.

Despite never being out of print and reissued several times in different couplings, Sing and Dance has never been so highly regarded as his later work with Capitol and Reprise or, for that matter, many of his earlier singles at Columbia or from the archives of his radio broadcasts. Not that it’s disliked, rather merely passed over, ignored, or just forgotten in overall assessments of his career. Certainly nothing intrinsic to the album itself accounts for this neglect: a first-class production with superb engineering, outstanding arrangements played by a band of cream-of-the-crop New York players, and Sinatra himself in absolutely top form. No less an authority than Will Friedwald, author of Sinatra! The Song Is You: A Singer’s Art (Scribner 1995), a magisterial critical study, calls it “one of the best albums of Sinatra’s entire career” (186).

Sinatra's last album for Columbia: in all but label affiliation the true beginning of the Capitol years.

Sinatra's last album for Columbia: in all but label affiliation the true beginning of the Capitol years.

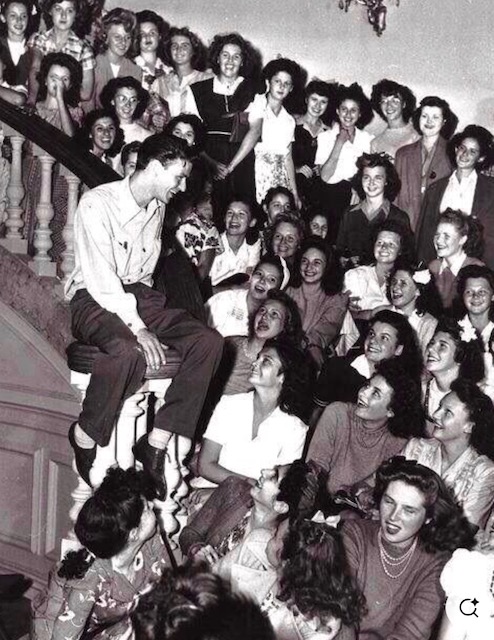

Although the album had disappointing sales and failed to place on the Billboard LP charts, Sing and Dance is now in retrospect easily seen as the watershed album that marked a convergence of several factors that would shape, even determine Sinatra’s subsequent development as singer, musician, performer, entertainer, and iconic artist-celebrity of the past century. Throughout the forties, when he rose with meteoric speed—a cliché, I know, but in this case the metaphor can be taken as literal—from being a rather local phenomenon around his native New Jersey and nearby Manhattan to an international superstar, Sinatra was known mostly as a singer of romantic ballads that drove the bobbysoxers who jampacked his engagements crazy— swooning, shrieking, and screaming, “FRANKIEEEEE!” But he always possessed a keen sense of rhythm, at once subtle and sophisticated, he loved jazz (Bing Crosby one of his idols), and he knew he could swing.

.jpeg) Bobbysoxers queuing up by the thousands for a Sinatra concert . . .

Bobbysoxers queuing up by the thousands for a Sinatra concert . . .

. . . and jamming themselves in to swoon over his romantic ballads.

. . . and jamming themselves in to swoon over his romantic ballads.

It would take several years and a fall as precipitous as his rise before he was in a position to prove it. His previous five albums for Columbia had all been variants of mostly similar material: love songs, torch songs, slow songs, sad songs (plus an album of Christmas music). It’s hard to imagine from our present vantage point that anyone ever seriously doubted Sinatra could swing, let alone sing jazz, but that was the general perception at the time.[1] With its rhythmic, up-tempo standards that are hip, happy, carefree, and gay (in the original meaning of the word), Sing and Dance was intended, conceived, produced, and performed to show that Sinatra could swing. Did it ever! Could he ever!

Ironically, for an album with musicmaking this upbeat, Sing and Dance was forged in the nadir of the most troubled period of Sinatra’s career, what Friedwald calls “All the In-Between years, 1948-53”. According to Charles L. Granata—whose Sessions with Sinatra: Frank Sinatra and the Art of Recording (A Capella Books 1999), at once detailed yet synoptic, is an invaluable comprehensive history of the singer as recording artist—the year “1951 was the lowest point in Sinatra’s life. Pop music trends were changing, and there was little interest in the sweet, pensive vocals that reminded many of the turmoil the war years” (68). His records weren’t selling as they used to, his movies were flopping, his concerts and nightclub gigs that were jampacked to overflowing just a few years earlier revealed large swaths of empty seats, Columbia records was ready to drop him, the prestigious agency MCA did drop him, he was reduced to booking singing dates himself (sometimes all but begging for those), he had gone from being a multimillionaire to flat broke, and he was in arrears with the IRS for at least a hundred thousand dollars in back taxes.

In addition to his superstardom as a singer whose artistry had led many critics and fellow musicians to acclaim him the finest interpreter of the American popular song—this when he was not yet out of his twenties and still more than a decade before the pinnacles of the Capitol and later years—his celebrity encompassed the soap opera of his personal life, which he lived to the hilt in full public view as a sybaritic playboy while trying to sustain an image, carefully coiffed by his publicist, as devoted husband and father who lived at home with his wife Nancy and their three kids. What this meant in reality is that most nights, whether performing, recording, making movies, traveling, or partying with his buddies and bedding a limitless supply of eagerly available women, he rarely returned home until the hours darkest before the dawn, and eventually he gave up even that pretense, instead maintaining a bachelor pad (more than one, in fact—Sinatra’s valet called him “the Casanova of modern times,” which from every available report and witness was not hyperbole).

By day the carefully coiffed image of the family man with wife Nancy and three kids . . .

By day the carefully coiffed image of the family man with wife Nancy and three kids . . .

. . . by night the voracious philanderer with a limitless supply of eager women.

. . . by night the voracious philanderer with a limitless supply of eager women.

When Sinatra fell hard for Ava Gardner and openly carried on the romance and courtship, humiliating his wife and confusing the children (nine, six, and two years old at the time), a disappointed public began to lose patience with him. After he finally asked Nancy for a divorce so he could marry Ava, many gossip columnists, especially those from the conservative Hearst newspapers, already hostile owing to his hostility toward them[2] (and to his progressive views—he all but worshipped Franklin D. Roosevelt), turned completely against him, while much of the good will of his fans continued to evaporate. (His flaunted—his harshest critics would call it fawning—association with known Mafia figures did only further harm.)

Ava and Frank: one of Hollywood's most tempestuous marriages.

Ava and Frank: one of Hollywood's most tempestuous marriages.

Vocal Problems

As if all this wasn’t bad enough, he began suffering from vocal problems, which were almost certainly the wages of too much tobacco, booze (the reported quantities of alcohol consumed day and night almost defy belief), carousing, womanizing, plus a congenital restlessness that turned him into a chronic insomniac (he once lamented he needed “pills to sleep, pills to get started in the morning, and pills to relax during the day”[3]), and a workaholism at times so punishing it seemed as if he himself were in competition with his voice to see which would give out first (it’s rumored that once he sang a hundred songs in a single day). On several occasions his voice gave out completely.

The worst occurred a couple hours after midnight on May 2, 1950, at the beginning of the last set at New York’s Copacabana, when he opened his mouth to sing and nothing came out—he tried again and tasted blood. His conductor that night was Skitch Henderson, who recalled, “His face chalk white, Frank gasped something that sounded like ‘Good Night’ into the mike and raced off the floor, leaving the audience stunned” (Kaplan, The Voice 428). The diagnosis was submucosal hemorrhage of the vocal cords, his doctor ordered several weeks’ rest, including no talking, let alone singing. Frank heeded the advice for maybe two weeks.

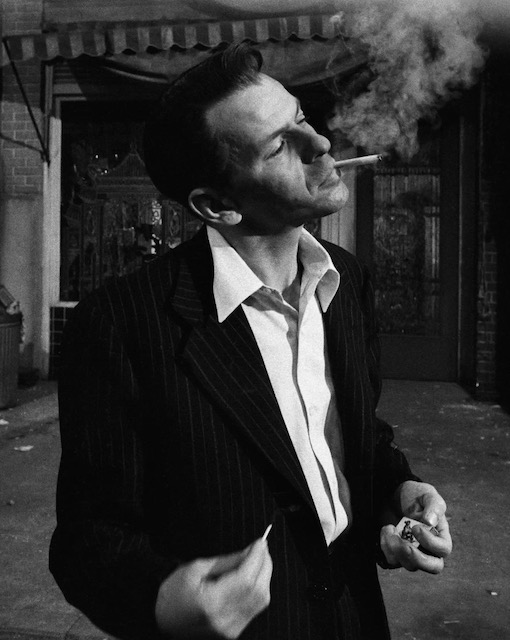

This image is from Otto Preminger's The Man with the Golden Arm, for which Sinatra drew upon on his own addictions to tobacco, alcohol, and high and hard living to play the title character, Frankie Machine, a down-on-his-luck drug addict and aspiring jazz musician.

This image is from Otto Preminger's The Man with the Golden Arm, for which Sinatra drew upon on his own addictions to tobacco, alcohol, and high and hard living to play the title character, Frankie Machine, a down-on-his-luck drug addict and aspiring jazz musician.

Yet one of the more remarkable things about Sing and Dance is how little the vocal issues or the professional and personal problems show up in the performances. There are couple of places where he goes for a sustained high note as the voice thins out a little—the very end of a terrific “The Continental”—but they are of no consequence, and it’s possible he left them in because the overall take is so damn good. (Another reason might have been the precarious shape of his voice—maybe he knew he didn’t have another full take in him that particular session.) That he was able to complete the album at all owes to a pair of relatively new technological developments: overdubbing and recording on magnetic tape, which facilitated the overdubbing.

When Sinatra showed up for the first of the sessions in March 1950 and began singing, his voice gave out almost immediately. Perhaps this was why he was ensconced in a booth, unusual for him because he always preferred to be in the same space with the band or orchestra so they could communicate more easily, thus play off each other the more effectively. Because so many players were booked, the producer Mitch Miller said that “to save the session, I just shut off his microphone, and got good background (orchestra) tracks. Didn’t even tell him!” (Granata, Sessions 66). Miller told Sinatra that when his voice recovered they’d come in and record him on a separate track that would be mixed over the orchestra tracks just laid down. His vocal problems were so persistent during this roughly two-month period that fully seven of the eight songs on the final album had to be overdubbed.

The artist as perfectionist, a workaholic who drove himself and his colleagues even harder in the studio than he played outside it.

The artist as perfectionist, a workaholic who drove himself and his colleagues even harder in the studio than he played outside it.

At the time Columbia Broadcasting System's technical resources were in advance of everybody else’s, including even RCA’s and Decca’s, and they had acquired the legendary CBS 30th Street Studio, a former church, a venue that was the envy of the industry. All the band tracks of Sing and Dance were recorded there, in sound that is pretty fabulous even without the usual “for the era” qualification: vivid, dynamic, richly colorful, yet with a mavelous capturing of air and atmosphere around the players and with balances that allow everything to be heard. The trouble was, when Sinatra did the overdubs, it was at the label’s studios on 799 7th Street, a very good venue but with different acoustics and, crucially, a different miking setup, noticeably much closer. The result was that Sinatra sounds dry next to the orchestra.

When I first listened to Impex’s 2020 release of this album four years ago, like most people I was bowled over by the warmth, the immediacy, the reach-out-and-touch-it presence of his voice. But the band struck me as somewhat “back there,” which I initially attributed to a combination of the balances and the fact that microphones, electronics, tape formations, and so forth of the day did not allow for the transparency in overdubbing we've taken for granted these last several decades. That might still be true, but I believe it’s the difference in the mike perspectives that is most responsible for the spatial and atmospheric discontinuity. (This is the only reason I've rated the sound 10 instead of 11.) As it happens, “It All Depends on You,” the song recorded several months earlier with Sinatra in very good voice and the only cut of the eight not overdubbed, demonstrates the difference right away on any good or better system: not so much in transparency, rather, that in direct comparison the overdubbing makes the voice appear more artificially present, whereas in “It All Depends” both voice and band sound as if they share the same space because of course they do.

One of the bonus tracks for the 1step release, and exclusive to it, is a much longer piece of the open-mike rehearsal during the “It All Depends” session, which lets you hear the difference from another perspective. Despite its being mono, the opening suggests a real sound space as you hear musicians and crew going about their business getting ready to record; later, when they do what appears to be the first run-through, in some respects it’s the best sound on the album because it’s so completely natural: inasmuch as it’s a preliminary take with Sinatra in the same room as the players, I suspect this is due in part to hearing balances before they’ve been adjusted at the console.

The other new technology that played a crucial role in this album is the long-playing vinyl record, which Columbia had introduced a year earlier. This combined with magnetic tape at last freed recorded music from the tyranny of the three-to-four-minute playing side of 78-rpm shellac records. Along with overdubbing and magnetic tape, the long-playing record was the third technological innovation that made it possible for Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra to become the first true Frank Sinatra Concept Album. Why? Because the whole point of a Concept album for Sinatra was to immerse us without interruption in a mood, an atmosphere, a style, a group of related feelings through an entire program of songs. This was at best only very imperfectly possible in the era of 78s, which required side-changes every two to three minutes. Little wonder Sinatra didn’t think in terms of Concept albums until the technology existed to make them possible.

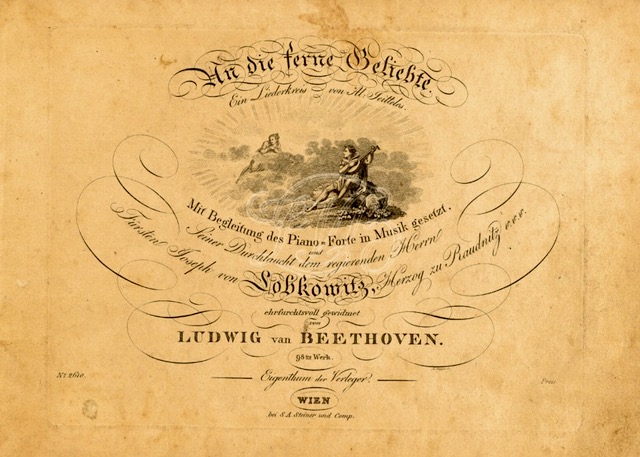

The Concept Album

The idea of the Concept Album did not originate with Frank Sinatra. If you think about it, the basic scheme of a group of songs unified by a central organizing principle, whether a theme, a mood, a metaphor, a style, a genre, a narrative, a character, or a state of mind or feeling, was anticipated at least 142 years before the long-playing record, with Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte (To the distant beloved), generally considered the first song cycle, then Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin (The Fair Maid of the Mill) and Winterreise (Winter’s Journey), the greatest of all lieder cycles. Of course, the music for those, as well as most subsequent song cycles in what is generally called serious or classical music, was composed by a single person setting a group of poems by another person. But Fauré, Richard Strauss, Mahler, Bernstein, and Rorem, to name just a few, all composed cycles culled from poems by diverse authors.

Beethoven's first and only song cycle: precursor to the Concept Album?

Beethoven's first and only song cycle: precursor to the Concept Album?

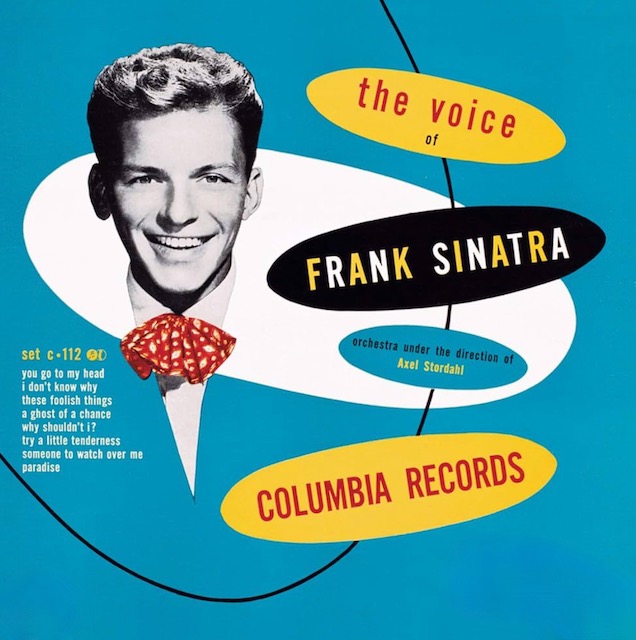

Much closer to the LP era, many critics and historians cite Woody Guthrie’s Dust Bowl Ballads, eleven songs released in three volumes on three 78-rpm records in 1940, as the first Concept Album. And closer still to Sinatra’s Capitol years are the other five albums he recorded for Columbia, beginning with The Voice of Frank Sinatra, both his first Columbia album and his first period. Released in 1946 as a box set of eight songs on four 78-rpm records, it shot to first place on the Billboard charts, where it stayed for seven weeks, then continued in the top five through August 1948. That same year Columbia introduced the 33⅓ long playing vinyl record and soon re-released The Voice as a 10-inch LP, the first catalogue pop album in the new format. In 1952 Columbia reissued it as a pair of 45-rpm EP (extended-play) discs, though the order of the songs was changed, then once more as a 12-inch LP in 1955, but with only five of the original songs and still a different sequencing. Finally, in 2003, Sony brought it out as a Legacy CD collection, with several additional songs on it.

Sinatra's first Concept album?

Sinatra's first Concept album?

I recount this history by way of questioning whether The Voice can be regarded as a genuine Sinatra Concept album. To be sure, as Granata argues, instead “of a haphazard collection of singles, it contained a thoughtful musical program”: “a number of similar tunes with orchestrations sharing a unifying spirit” (47). And the songs themselves and Sinatra’s interpretations do suggest an overall mood that is ruminative, thoughtful, soulful, all couched in the storied Axel Stordahl’s sumptuous arrangements. But The Voice still seems to me more like an embryonic notion of what a Concept album might be than the thing itself. For one thing, what true Concept album that Sinatra ever made allows for the addition or subtraction of songs without changing, typically for the worse, the overall experience? For another, Granata himself points out that whoever came up with the idea, it seems not to have been Sinatra. (It might even have originated with the label's marketing department!) For a third, the songs were drawn from a combination of new recordings and some already in the vaults. In other words, they weren’t recorded for an album with a specific Concept in mind; rather, after they were gathered together, a Concept of sorts was extrapolated from them. The same is true of the other Columbia albums that preceded Sing and Dance.

Then, too, the titles of the Concept albums Sinatra himself created almost always articulate or otherwise suggest the theme or unifying principle: Only the Lonely, No One Cares, Close to You, Songs for Swinging Lovers, Come Fly with Me, Where Are You?, September of My Years, Moonlight Sinatra, etc. But The Voice of Frank Sinatra not only suggests nothing of the sort, it actually sounds like a title designed to introduce a new singer as opposed to one who was already a household name. Meanwhile, Christmas Songs by Sinatra and Songs by Sinatra, Volume One are in no meaningful sense Concept albums either, while Dedicated to You and Frankly Sentimental don’t escape the merely generic. As regards the last named, given the care and thoughtfulness with which Sinatra created his later Concept albums, it’s impossible for me to believe he would have put a song filled with as much despair as “One for My Baby (and One More for the Road)” on an album of songs he considered merely sentimental.

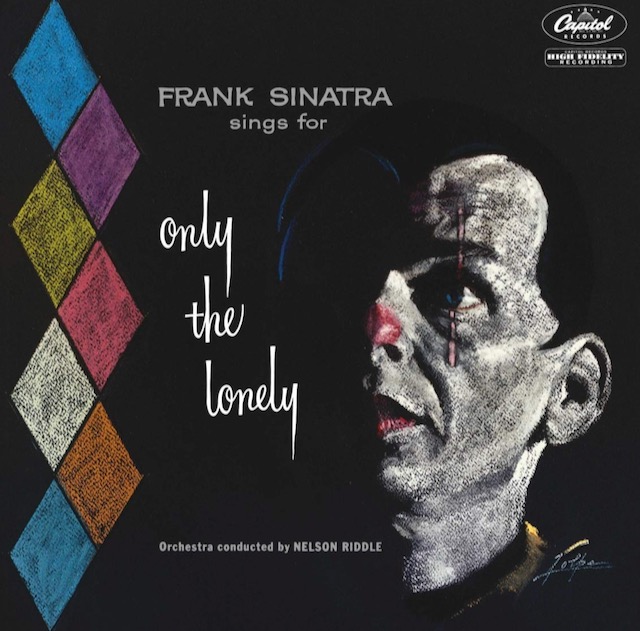

It wasn’t until 1958 and Only the Lonely, Sinatra’s and Riddle’s favorite collaboration and perhaps their most impressive single achievement in Concept creation, when he finally got round to putting that particular song where it belonged. The effect is shattering. “Only the Lonely,” the title song, written for the recording, introduces the heartbreak that sets the rejected hero on his journey; “Angel Eyes,” placed second, one of Sinatra’s greatest single performances, begins the descent into isolation (“s’cuse me while I disappear”); then step by step the selections move with the inevitability of tragedy toward last call in that desolate saloon at quarter to three in the morning and the road from which there will be no return: one for my baby, one more for the road, that long, it’s so long, the long, very long—the voice trails away without explicitly indicating the wanderer’s fate . . .

I’m not arguing this cycle is as great as Winterreisse—Only the Lonely is a compilation, not an original composition—but the structure, the theme, and the implied narrative are parallel and the emotional effect is not dissimlar: devastating heartbreak leading to grief-laden wandering through the first half, grief giving way to despair unto death in the second half.

Perhaps Sinatra's and Riddle's most impressive single collaboration.

Perhaps Sinatra's and Riddle's most impressive single collaboration.

In some of my past writings on Sinatra, I’ve referred to his Concept albums as “recitals,” a term that comes from art-song recitals in classical music. Pretentious? Maybe, but remember that once Sinatra realized what he could do with the Concept Album, he planned the programs, selected the songs, had them arranged, and ordered the sequencing in meticulous and purposeful detail. And he was so committed to his Concept—his vision, if you will—for each of them that he rarely and only reluctantly countenanced release of the individual songs as singles.

More than most singers, and more than almost any before him, Sinatra looked to the lyrics of a song for its meaning. Whether slow and melancholy, passionate and romantic, or carefree and swinging, he wanted his listeners to attend to his Concept albums as if they actually were art-song recitals. He approached the Great American Songbook, Tin Pan Alley, and songs from Broadway and movie musicals as the miniature masterpieces they are. I do not use “miniature” condescendingly. Like the ABA or ternary structure of the classical art song, so the 32-bar structure (AABA) of American popular songs is as tightly organized yet as flexible and as richly expressive and has left us with a commensurate body of masterworks second to none.

It’s also worth noting that the Great American Songbook, that loose collection of Tin Pan Alley, Broadway, and movie songs which Alec Wilder surveyed in his pioneering critical study American Popular Song: The Great Innovators, 1900–1950 (Oxford University Press 1975), did not really exist, at least as we know it today, when Sinatra first rose to prominence. This is because, as Granata points out, it was through Sinatra that many of the songs became standards. Not only was he one of the greatest interpreters of American popular song, but it was also his advocacy through his career-long quest for the best material which helped make them standards.

Before he was halfway through the sixteen albums he recorded for Capitol, the Concept Album was fully launched as a commercial and a musical form that would influence countless singers and bands from Harry Belafonte to Ella Fitzgerald to Bob Dylan to the Beatles to Paul Simon to most recently Taylor Swift and Beyoncé (Cowboy Carter). It has even made serious incursions into classical music, e.g., Hélène Grimaud’s Water, Víkingur Ólafsson’s From Afar, Bertrand Chamayou’s Letter(s) to Erik Satie, so much so it’s now a category in Gramophone’s album of the year awards.

Another Ending, Another Beginning

Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra was originally released as a 10-inch, 33⅓ LP and a four-disc 78 set, typical in the first few years of the long-playing vinyl record because by no means did consumers en masse immediately embrace the newer format. As is not the case with the other Columbia albums, Sing and Dance has a real thematic unity in addition to singing and dancing: the songs are all about the early stages of romance, about falling in love, often before feelings have been requited or even recognized, and they celebrate or otherwise express the euphoria, the anguish, the joys, the fears, the passion, the jealousy, the self-absorption, the infatuation, the idealizing and the pleading. Yet there’s nothing pretentious, heavy, inflated, or handwringing about it. On the contrary, this is light music at its glorious best and one of the most sheerly entertaining albums Sinatra ever made. His command of swing is as if to the style born, and he pierces to the core of every song with a control of tone, a word I use in the literary sense of the artist’s attitude toward the material, at once absolute yet so natural and intuitive he makes singing sound as easy as whittling a stick.

Perhaps the lion’s share of the credit for the musical and stylistic unity yet the diversity within each song must go to the arranger George Siravo. Siravo was a first-rate arranger who had worked with Sinatra before. He never became a big name like Riddle, Stordahl, Billy May, Gordon Jenkins, and Don Costa, preferring to work behind the scenes. Sinatra often used him to score the up-tempo numbers the ultraromantic Stordahl couldn’t (or at least didn’t) do. And he composed all the charts but one for Sinatra’s first Capitol album, Songs for Young Lovers.[4] Big, bold, brassy, and brilliant, the charts here—Siravo’s wizardry makes the complement of fifteen to seventeen players, who play as if having the time of their lives, sound much larger—hark back to the heyday of the big bands with whom Sinatra had cut his teeth, before singers who struck out on their own, such as himself and Crosby, began replacing bandleaders as the superstars in popular music.

The issue of who exactly was responsible for the song selections and their order persists even with Sing and Dance. Mitch Miller always insisted it was his idea to have Sinatra to do a whole album of rhythmic pieces. In Sessions with Sinatra, Granata quotes Siravo to the effect that “Frank didn’t even pick the tunes. I picked the tunes, I picked the keys, I wrote the arrangements . . . he didn’t even know what the hell he was going to sing!” (67). Yet in the new essay Granata wrote for the Impex 1step, “Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra: Celebrating an Essential American Classic,” he argues there’s "no doubt it was Sinatra himself who chose the songs he wanted to include. And it’s likely he sequenced the songs very carefully” (22). I’m not entirely convinced that “likely” can support the weight of the assertion. But in the grand scheme of things, does it matter who proposed the album and helped select and order the songs? What really matters is that it was Sinatra alone who first grasped what could be done with the idea of the Concept Album and in a few years would extend, develop, and realize it with a depth, scale, range, and variety that, in Granata’s words, “turned it into an art form.”

Whose idea was Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra: George Siravo's, who wrote the charts and claimed credit for picking the songs;

Whose idea was Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra: George Siravo's, who wrote the charts and claimed credit for picking the songs;

or the producer Mitch Miller's, who always said it was he who first proposed Sinatra record a whole set of uptempo songs?

or the producer Mitch Miller's, who always said it was he who first proposed Sinatra record a whole set of uptempo songs?

A further point amply demonstrated in the open-mike bonus cut is that it shows how Sinatra worked with his producers, engineers, recordists, and fellow musicians, especially how totally in charge he was, how alert even to the smallest details, and how completely he knew what he wanted to do with each song and each album. Here he’s fastidious about instrumental balances and the sounds of the instruments (he loves the muted trumpets, for example); at one point he inquires whether the trombones could be brought closer so they sound really together, at another if the drum has enough damping (he asks someone to attach a piece of carpet to the underside to tighten the sound bit). Although Sinatra was never formally trained in music and could not read it, he was born with a fantastically acute pair of ears that evidently missed nothing and a native musicianship for which the word “genius” is not overstatement. According to the pianist Stan Freeman, “I remember him being very aware of what he wanted, and getting it. If he thought a flute or an oboe part should be left out of one section, he would say so. He didn’t have to take charge, but nominally he was in charge—and everybody knew that. He was always very pleasant, never any tantrums or anything” (Granata, Sessions 56).

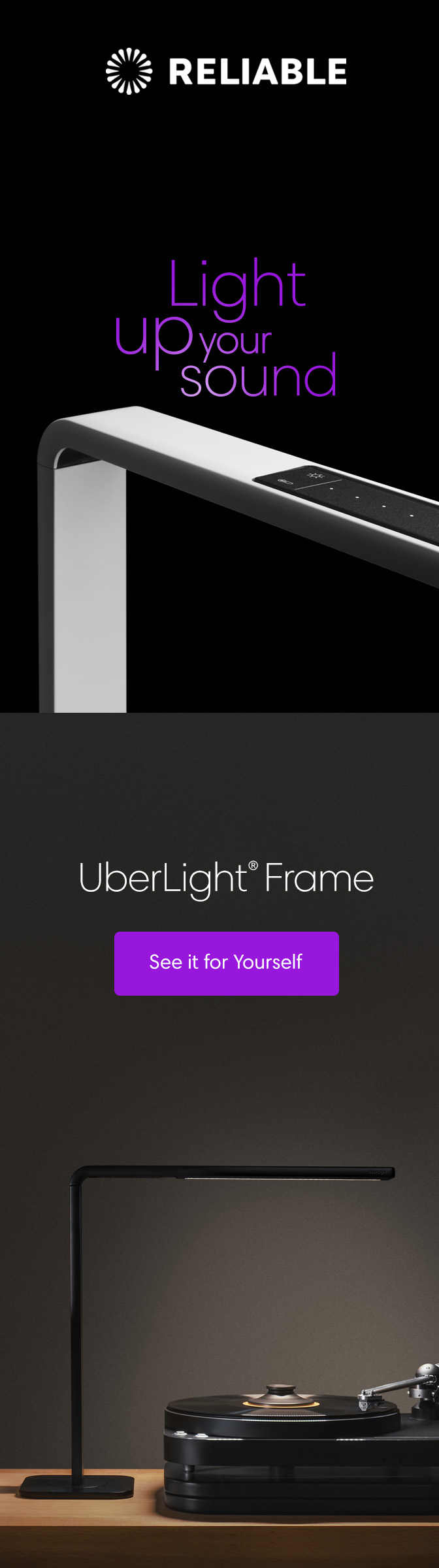

When it comes to giving legacy releases like this the full super-deluxe treatment, I can’t think of anyone who does it better than Impex Records. The 2020 edition was given a classy gatefold presentation that reproduced the original cover art and an outstandingly detailed booklet by Granata, adapted from Sessions and further augmented with vintage photographs and much technical information about the provenance of the recordings in the original 15-ips masters, which “have lain untouched in the Columbia Records vaults for more than fifty years.” With the reservations previously noted, sonics are state-of-the-art circa 1950. There are places where you’ll hear some tape saturation at climaxes, but these are minor and in no way detract from the musical experience.

So when I heard Impex were bringing out a new version of Sing and Dance, I wondered how much better could it be. As someone not exactly overwhelmed by the putative superiority of some of the 1step releases I’ve heard so far, I was skeptical. And then nearly floored: Sinatra’s voice has even more reach-out-and-touch it body and tactility; the sonic picture is more open, with greater warmth, transparency, dynamic range, and sheer vividness. Inasmuch as all the original source materials are identical and the same people were involved in preparing the new release, I telephoned Impex’s Abey Fonn, one of the executive producers of the album, to inquire what was done. She told me there was some very minor re-equalization in a few spots, a little tweak here, a tiny boost or cut somewhere else, but that was it. The 1step process? Of course that had to help, along with the 45-rpm cutting. But Fonn attributes the major improvement to Neotech’s new VR900-SUPREME vinyl formulation, which Granata in his technical notes calls “startlingly revealing”. Using “new chemistry” and “raw materials,” Neotech developed a compound that reduces groove noise, providing “ultra-quiet grooves as well as incredibly precise groove definition.”

Whatever manufacturing and chemical methods, materials, and compounds were used, I’m pretty sure I’ve never heard quieter surfaces or a cleaner overall reproduction as far as the vinyl itself and the surfaces go. As for the packaging: “Heavy-Stock 3-Sleeve Monster Pack Jacket with Gorgeous Tip-In 36-Page Booklet & Luxe Color-Matched Slipcase! Strictly Limited to 5,000 Numbered Pressings!” The heavy stock is a particularly welcome touch compared to the flimsy (read cheesy) stock used in DG’s Original Sources Series vinyl reissues, while DG's woeful lack of additional supplementary notes about the restorations and the performances themselves is embarrassing next to the thirty-one pages of history, technical information, and photographs supplied by Granata. The whole set is housed in a classy and sturdy ecru slipcase. The 5000 copies are pressed only in batches of 500, which requires the cutting engineer, here Chris Bellman of Bernie Grundman Mastering, to return to the master tape and recut an additional first-generation lacquer for each new run.

Of course, all this comes at a premium price of $129, over twice that of the 2020 gatefold release and over four times that of Impex’s 2020 SACD release, both of which still sound excellent. If that seems like a lot, consider that in 1970 a standard-issue topline full-priced LP from the major labels retailed for around $6.00. Adjusted for inflation, that comes to about $48 in today’s world. Multiply this by two since it’s a two-disc set and you’re at $96. Given the beauty of Impex’s presentation and the high technical perfection of the LPs, $129 does not strike me as in the least unreasonable—on the contrary, it's rather generous. Meanwhile, the importance of this album in the overall development and history of Sinatra as an artist, of the LP as a medium that is still thriving, and of the intersection of jazz and popular music cannot be gainsaid.

It remains only to be observed that three years later, when Sinatra began recording for Capitol, four of the sixteen Concept albums he made there before he departed in 1963 for Reprise have “swing” or its variants in the titles, and seven are swing and jazz in orientation. In his first several years at Reprise, he laid down at least eight jazz albums collaborating with the likes of Johnny Mandel, Billy May, Nelson Riddle, Neal Hefti, Count Basie, Quincy Jones, Carlos Antonio Jobim, Duke Ellington, and Don Costa.

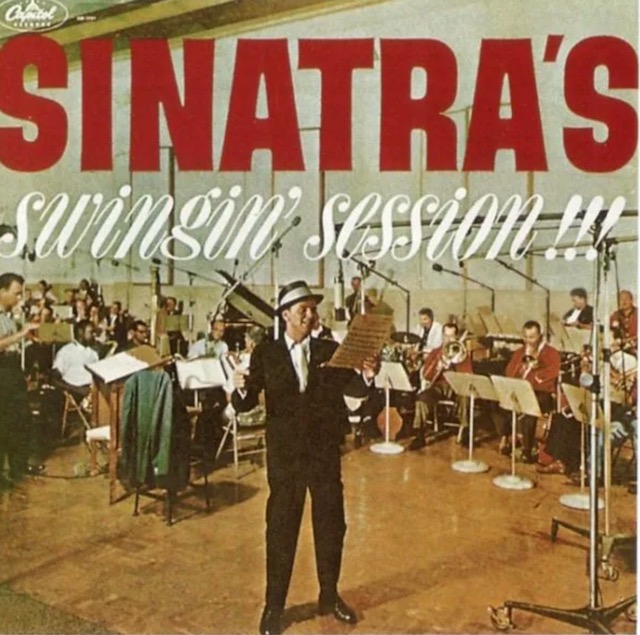

In 1961 came one of his last albums for Capitol, Sinatra’s Swingin’ Session!!!, in which he re-recorded six of the eight songs from Sing and Dance, this time with charts by Riddle. The comparison is revealing. The earlier album finds Sinatra in full proving-himself mode, with performances and arrangements that are faster, punchier, more overtly virtuosic. The later album, superlatively recorded in the still relatively new medium of stereophonic sound, finds him more relaxed and easier going, yet if anything exuding even greater confidence because by then he had nothing to prove. He had become the poster child, nay, the living embodiment of the quintessential swinger who had long since shown that he could conquer the world of jazz as easily as he had that of traditional popular music.

Eleven years later Sinatra re-recorded six songs from Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra, in superlative sound in the relatively new medium of stereophonic reproduction.

Eleven years later Sinatra re-recorded six songs from Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra, in superlative sound in the relatively new medium of stereophonic reproduction.

With that granted, however, it must also be said that the eleven years separarting the two albums had taken their share of a toll. Sinatra was thirty-five when he recorded Sing and Dance—not a young man thusly defined, but he still had a young voice, and that made all the difference. If ever there was a young man’s album with young men’s music, Sing and Dance is it. By the time of Swingin’ Session Sinatra was forty-six, hardly old by any reckoning, yet the voice is older, his baritone had deepened, slightly roughened, and lost a fraction of its range and agility. It was a more mature voice, throatier, and in most respects a richer one, better able to serve a sensibility that drew ever deeper upon the complex life experiences of a complex man. From this perspective, Sing and Dance is one of those instances in the performing arts—for any of several reasons, they often happen by chance—where a singer sang exactly the right repertoire at the exactly right time with the best technology of the day there to capture it.

Let us all be grateful to the enterprising folks at Impex, to all their technical personnel for the tender loving care they lavished on this project through every stage of its production, and to Charles L. Granata for his dedicated stewardship of this great artist’s recorded legacy.

[1] The question whether Sinatra was or became a true jazz singer has persisted in some circles throughout his career. As late as 1998, the year the singer passed away, Gary Giddins was writing in his authoritative Visions of Jazz: The First Century (Oxford), “Sinatra was of jazz rather than being in jazz” (226); though it must be added that Giddins also writes more appreciatively, perceptively, eloquently, and knowledgeably of Sinatra as entertainer, singer, and serious artist than any other critic this side of Friedwald, and he’s scarcely less an expert.

[2] Sinatra once sucker punched a male columnist, insulted the looks of a female columnist on national television, and was forever threatening the reporters and photographers who dogged his public appearances.

[3] Quoted in James Kaplan, Frank: The Voice 417. Kaplan’s biography, in two volumes, the second called Sinatra: The Chairman, both published by Doubleday (2010 and 2015), is by several orders of magnitude the best biography of the singer and one of the best biographies of any popular singer. It’s also one of the four best books on Sinatra, the others being Friedwald’s, Granata’s, and Pete Hamill’s lovely Why Sinatra Matters (Little Brown 1998), a socio-cultural portrait by a journalist who knew him, with notably insightful comment on the significance of the immigrant experience on Sinatra's art and celebrity.

[4] The one was by Riddle. Nobody seems to know how or why Siravo’s name appeared nowhere on the album, but he was deeply disappointed and understandably resentful. Riddle, for his part, felt guilty about it his whole life, even though it was not his fault.

email from Charles "Chuck" Granata to IMPEX's Abey Fonn (reprinted here with permission:

Wow-wow-ee!

To say I’m bowled over doesn’t begin to describe the feeling I got while reading Paul’s review. I can’t remember any record review I’ve ever read - emphasize EVER - in which the reviewer has such a deep, firm command of not just the overall history of music and sound recording, but the subject (Sinatra) itself. What a gem! I’m grateful for his kind words for each of us; more than this, I stand in awe of his knowledge of and appreciation for the “backstory.” He understands how vital this album was in the scope of SInatra’s lengthy (and complex) body of work, and beautifully explains that to the reader. Bravo, Paul! I especially love the references to the classical “song cycles,” which I’m somewhat familiar with but never thought to compare the concept album to. That’s nothing short of brilliant! This is what I love about our collective “takes” on the music we love; each of us is passionate - and in our own way - and can bring fresh insight into the analysis. In this regard, Paul is a treasure!

Thanks for sharing - you made my Christmas!

Love to all for a warm, wonderful holiday . And thanks for being such great friends…

email from Granata to Paul Seydor (also reprinted here with permission):

Hello Paul,

Pardon my delay in responding to your wonderful email; my dad passed recently, and it has been a bit hectic settling his estate the past few weeks.

I am SO happy that you enjoyed the new version of "Sing and Dance." The original master tape was in pristine condition, and responded well to the entire process. As you note, even though there were some 'hot spots' with slight tape oversaturation, that is exactly what the charm of those early analog mag tapes is! I find that almost imperceptible distortion to be very appealing, and a huge part of why we're attracted to analog sound. Some tapes survive the process from transfer-to-lacquer cutting and pressing and retain that charm; for others, it doesn't translate as well. We were fortunate that everything came together almost perfectly for us with both the 33-RPM and 45-RPM 1-Step LPs on this title.

Your kind words for "Sessions with Sinatra" are truly meaningful. It pleases me tremendously knowing you enjoyed it - and shared it with Ron Shelton! I still quote "White Men Can't Jump," and am an admirer of his work (and yours) - and am thrilled that we are able to connect. As a film buff, I appreciate and study all aspects of what you do when watching films; editing - whether audio or visual - is such a fine art, and most people never consider how much a skillful editor adds to their enjoyment of a movie. You have my deepest respect!

I also have a deep love for classical music - in all its forms. Beethoven is a particular favorite. Although I never had the chance to interview Frank himself, I would have certainly used a good amount of time probing him on his attraction to classical music. It was not merely something he said to appear erudite in interviews; Nancy attested to how much he enjoyed playing opera music when he was with his father (Marty), and Billy May told me that he and his wife often attended the symphony in Los Angeles with Frank and Barbara. When they first began going to concerts, Billy was impressed that Frank knew the background of the pieces being featured - including those by less mainstream composers such as Gliere. It was what he listened to and read about during his down time in the desert, and he applied many of the musical nuances he heard in classical to his own arrangements (via the Stordahls, Riddles, etc.) For someone who had no formal musical education, he was a brilliant musician!

The connection you made between classical art song cycles and Sinatra's thematic albums of the 1950s and 60s was superb! I'd never considered that, but it makes perfect sense. Again, one of the questions I'd have asked him - one which he would probably give me an odd glance for, since no one ever asked him such deep musical questions (LOL).

I'd love for you to join me soon on my weekly radio show (Sinatra Standard Time) on KSDS-FM in San Diego. We can definitely talk about any topic related to the American Songbook, composers, how classical influenced pop music, etc. - whatever you like. It would be fun! Both you and Ron have an open invitation to talk Sinatra and music, ANYTIME...

Please keep in touch and let me know if there's any Sinatra music you're looking for...

Best wishes for a warm, healthy and safe New Year!

Always,

Chuck

P.S. Here's a link to my radio show and KSDS's archive of shows. Feel free to share with Ron!

P.P.S. Of course, I hope you share anything you like with Michael Fremer - love his work, too