Playing For The Man At The Door

Smithsonian Folkways issues a 6 LP set of Mack McCormick's legendary field recordings

In 1957, Robert "Mack" McCormick began working as a cab driver in Houston, Texas. He was twenty-seven, and to that point, his life had been one of debilitating depression, rootlessness, dissatisfaction, and failure. He and his mother had moved twenty times before he was sixteen. Listening to jazz and big band broadcasts was the joy of his drab and lonely life. At fifteen, he hitchhiked to New Orleans to meet Orin Blackstone, who was compiling Index To Jazz, the first American jazz discography, and who offered him the job of "Texas Editor." McCormick returned to Houston with the title but never heard from Blackstone again. Despite high intelligence and winning a statewide "Best Essay" contest, he failed to graduate high school. He began writing for Downbeat as the probably unpaid "Houston correspondent." When he was nineteen, he started forging checks, was arrested, and spent nearly a year in prison. While on release probation, he continued to write for Downbeat but could not make monthly restitution payments and was forced to sell his furniture and record collection. In a curious mixture of despair and bravado, he wrote to his mother, "I have decided to slip into the vagrant-bum-drifter class to which I actually seem to belong," but somehow, he retained faith in his talent and struggled on through episodes of depression and paranoia, trying to find his way, working dozens of menial jobs, most for only a few days or weeks before he was fired or quit. For periods, he depended on his mother for support, though she, too, was troubled and also had difficulty finding steady employment. He wrote to her that he couldn't adjust to work because, "Very simply, I have more important things to do...At the moment---as for the past four years---that more important thing to do is writing." But then McCormick admitted to her that he had never written anything he wasn't ashamed of.

Driving a cab suited him. He could work the hours he chose, take time off if he was depressed, and not have to work with others. The job also allowed him to hunt for records, talk to Black customers about music and become familiar with life and the clubs in the Fourth Ward, Houston's Black neighborhood where there was a thriving music scene that included up to date rocking R&B but also older country blues styles being played on the streets, in bars, and at parties. He also heard other music: Czech songs, Texas swing, Cajun, Zydeco and Conjunto. Later he said, "People thought folk music was over," he said. "I realized that wasn't true."

McCormick sensed an opportunity in the blues he heard in the Fourth Ward. In 1957, there had been many books published on the history of jazz, and considerable information was available on just about all the major musicians, but there were no books on country blues. Jazz writers ignored blues, considering it repetitive, stupid, salacious dance music. The audience for 20s and 30s country blues was tiny, maybe two dozen collectors who traded tapes of their record finds and the latest rumors and speculation about the artists who were only mysterious names on record labels---Blind Lemon Jefferson, Barbecue Bob, Furry Lewis, Peanut The Kidnapper, Funny Paper Smith. McCormick knew that many of the musicians who had recorded in the '20s and '30 were still alive and those who had died were remembered by family, friends and other musicians. Country blues was virgin territory for research. McCormick became, in his words, "…a collector, a student, an investigator of the folklore at hand." He had found something important to do.

Using scraps of information circulating in the collector world, clues from records like the singer's accents, the names of towns mentioned, and his intuition, he began searching for information on blues singers. In those pre-internet days, his method was simple but effective. He talked to people and asked questions. Most of the people he spoke to were Black and understandably suspicious of a white man asking questions in their neighborhoods, but they gave McCormick information. Probably, they knew immediately from a lifetime of dealing with white authority figures that McCormick was not one of those, and his story about searching for blues singers was so bizarre it had to be true. One lead led to another, and soon he was traveling widely through Texas to towns where blues singers had lived or worked. He was tireless, obsessive and compulsive, and went door to door using a grid pattern, asking for any scrap of information about singers that had recorded, but also any singer that might have played on the corner or at picnics or just on his porch.

He was the right man in the right place and time and uncovered a vast quantity of information, all of which was summarized and detailed in notebooks, to be later typed up and cataloged. Amongst the tiny cadre of collectors and the even smaller group of blues researchers, he became the acknowledged expert on Texas blues and began collaborating on a book on the subject with the British author and researcher Paul Oliver, who had written extensively about blues for magazines. The book project spurred him to even greater effort, and McCormick documented the lives of dozens of blues singers and made some truly amazing discoveries---he located Blind Lemon Jefferson's younger sister and the second known photograph of him, he found relatives of Leadbelly and unearthed important biographical information, he found a relative of Henry "Ragtime Texas" Thomas whose "Bulldoze Blues" was lifted by Canned Heat for the melody of "Going Up The Country" and established that Thomas was born in 1874, making him one of the oldest recorded blues singers. He did all of this without any academic affiliation or subsidy while living in near poverty.

He broadened his scope beyond Texas to what he called "Greater Texas," which also included parts of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma, and during the 60s, did research in more than 700 counties. In the late 60s, his canvassing trips began to focus on musicians he was particularly interested in, and Robert Johnson, of whom almost nothing was known and already a legend, became what he probably viewed as the mystery that, if solved, would prove him to be the foremost blues researcher and provide the material for a book that could establish a successful writing career.

He made multiple trips to door knock in Mississippi and chase leads. In his words, "Very slowly and gradually, a few breakthroughs were made. Each one stands amid dozens of false starts and dead ends, but during the 1970-73 period I located former neighbors and friends who had known him as a youth. I also traced his children, two half-sisters, a widow and women who had known him closely if briefly….The work involved travel to Los Angeles, Chicago, St Louis , Maryland and other places where the people of Mississippi have scattered. These travels produced photographs of Robert Johnson, his family as well as related documents and memorabilia. It also produced two concise, confirmed eye witness accounts of his murder.”

McCormick had solved as much of the mystery that could or ever will be solved, and Johnson's half-sister, Carrie Thompson, signed an agreement to allow her words and the photographs to be used in a book by him. His Johnson research should have brought him acclaim, a career as a respected folklorist, a series of published books, guest lectures, and possibly an academic position, but his mental illness and personal failings made him throw it all away.

McCormick had a falling out with Carrie Thompson, and in 1973, she signed a contract with another blues researcher, allowing him to manage the estate of Robert Johnson. An agreement was made with Columbia Records to release the Complete Recordings. According to The Man At The Door booklet, "McCormick refused to return family photographs that she (Thompson) had lent him, created fraudulent documents that he claimed Thompson had signed, and stalled a major Columbia release of Johnson's recordings for fifteen years."

Probably not coincidentally, McCormick's mental illness worsened as his battle with Robert Johnson's estate and a resulting lawsuit against him dragged on. Robert Johnson---The Complete Recordings was finally released in 1990, without the involvement of or any mention of McCormick, to intense media interest and acclaim and the heretofore unimaginable, for country blues, sale of over one million copies. Johnson's improbable transformation from obscure bluesman to pop star and icon was not also the occasion for the world's recognition of McCormick's equally improbable transformation from troubled high school dropout to the world's foremost folklorist.

During the rest of his life, he became increasingly paranoid, intentionally feeding blues researchers false information and believing that they wanted to steal his archive. He wrote unsent letters threatening violence to those on an enemies list he created. His constant disputes with Paul Oliver ended their collaboration after years of work, leaving the Texas blues book incomplete. He could be generous and cooperative with writers and researchers who asked for his help and then turn on them with vicious, paranoid accusations. His daughter Susannah said, "My entire life I watched the cycle repeat, It didn't matter who he dealt with, he would alienate them, and they would alienate him. He couldn't make decisions; he got hung up on minor details. It was his illness, it was his personality, it was his age.”

The cycle she spoke of doomed McCormick's Robert Johnson book. Initially, it was eagerly awaited, then became the focus of annoyance with what was perceived to be McCormick's procrastination, then anger with him for refusing to publish because of seeming egotism and selfishness. After years of promises but no publication, the book became a legend, and many believed it was a fantasy that had never existed except in McCormick's imagination. Actually, he wrote hundreds of pages, but whether because of contrariness or because his mental illness made him turn against the Robert Johnson that he had found and helped make an icon, McCormick denounced all the research he had done as a great mistake, claiming that the Robert Johnson in Mississippi was not the man who had made the records. The "real" Robert Johnson was instead a Texas musician. Evidence for this new theory was flimsy, possibly fabricated and the reasoning behind it preposterous. McCormick's Johnson book, entitled Biography of A Phantom was never completed by him.

Until his death, McCormick lived reclusively in a modest house in Houston that also housed his archive, which he referred to as "The Monster." He refused all access to it, and the file cabinets were chained and locked. McCormick, who suffered from severe writer's block, probably exacerbated by his bi-polar illness, dubbed himself "the king of unfinished manuscripts" and did not publish any significant writing after 1975, when his superb liner note essay appeared on the Herwin Records issue of the complete recordings of Henry Thomas, which critic, Greil Marcus said were "the best notes of their kind I have ever read." McCormick's interest in blues apparently waned. The study of Emily Dickinson and her poetry and writing plays, all unproduced and possibly never completed, occupied his time.

In 2014, the blues world was shocked when the New York Times Magazine published a cover article on L.V. Thomas, a female blues singer who, in March 1930, recorded with another female blues singer, Geeshie (sic) Wiley, at a session that produced three 78s. Neither woman ever recorded again, and nothing was known about them. The eerie, haunting quality of the music and the mystery of who the women were, where they came from, and what happened to them after that single recording session had inspired speculation among blues collectors for decades.

Mack McCormick had known the answer to these questions since 1961 when he interviewed L.V. Thomas at her home in Houston, but he never shared the information with anyone. That the answers were provided in a long article in the New York Times Magazine was solely due to actions, which might be viewed either as brave and intrepid historical preservation or as theft and a breach of journalistic ethics, by a young assistant hired to help organize McCormick's massive archive and who without permission photographed the notes of his interview of L.V. Thomas and by author, John Jeremiah Sullivan who quoted them extensively in his article. Sullivan defended their actions, "You're not allowed to sit on these things for half a century, not when the culture has decided they matter." McCormick's daughter, in a letter to the New York Observer wrote, "It would be impossible to overstate the damage this incident has done to my father's physical and mental health." It seems to me profoundly tragic and sad but not surprising that when fame finally came to McCormick and his work, it came against his will, and he gained not acclaim but a dubious notoriety.

McCormick died in 2015, and his daughter donated his archive, which consisted of 90 linear feet of field notes, interview transcripts and writings, over 4000 photographs, and approximately 290 tapes of interviews and music, to the Smithsonian Institution.

A large portion of the tapes were "field" recordings McCormick had made of musicians playing and singing in their homes, the streets, or in clubs after he began documenting "folklore" in 1958 with a borrowed tape recorder, a $150 grant from the Houston Folklore Society and a cache of blank tape donated by the Texas Folklore Society. A good field recordist needs the skills of a detective and a psychologist as well as those of a folklorist. McCormick was eminently qualified and proved to be an excellent recording engineer as well. He recorded bawdy songs and jokes which seemed to be one of his particular interests, white country music, gospel, folk ballads, zydeco, Welsh hymns, ranchera, and, of course, blues.

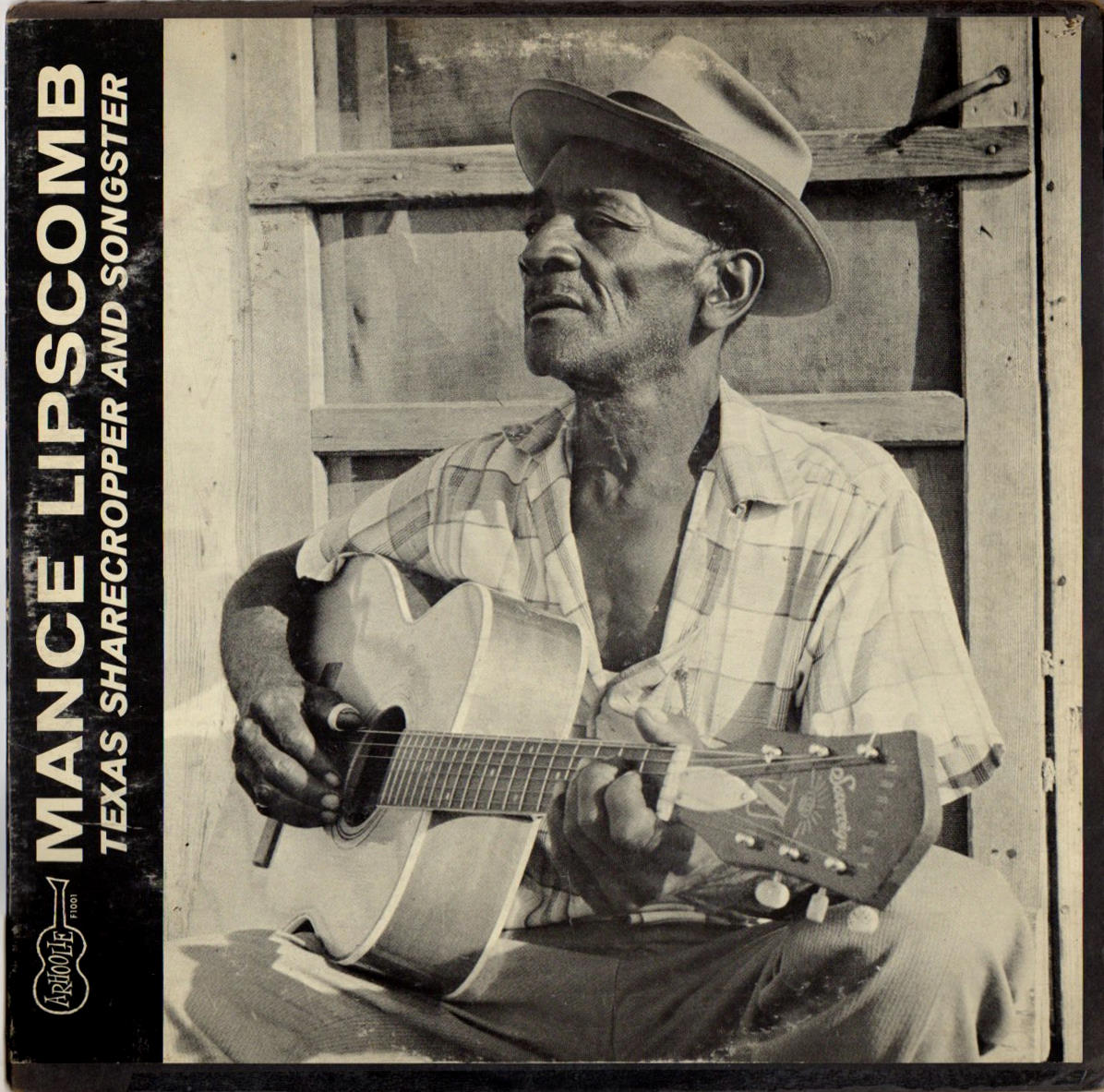

Many of McCormick's recordings were commercially issued. He recorded Lightning Hopkins at eight sessions in Houston in 1959, and four albums were released. In 1960, with Chris Strachwitz, he made recordings of Mance Lipscomb at his home in Navasota, Texas, which were issued as the very first Arhoolie album. McCormick wrote a long and brilliant essay for the album, of which Strachwitz said later, "I don't think anybody has achieved the feeling that Mack McCormick can put into his notes. “

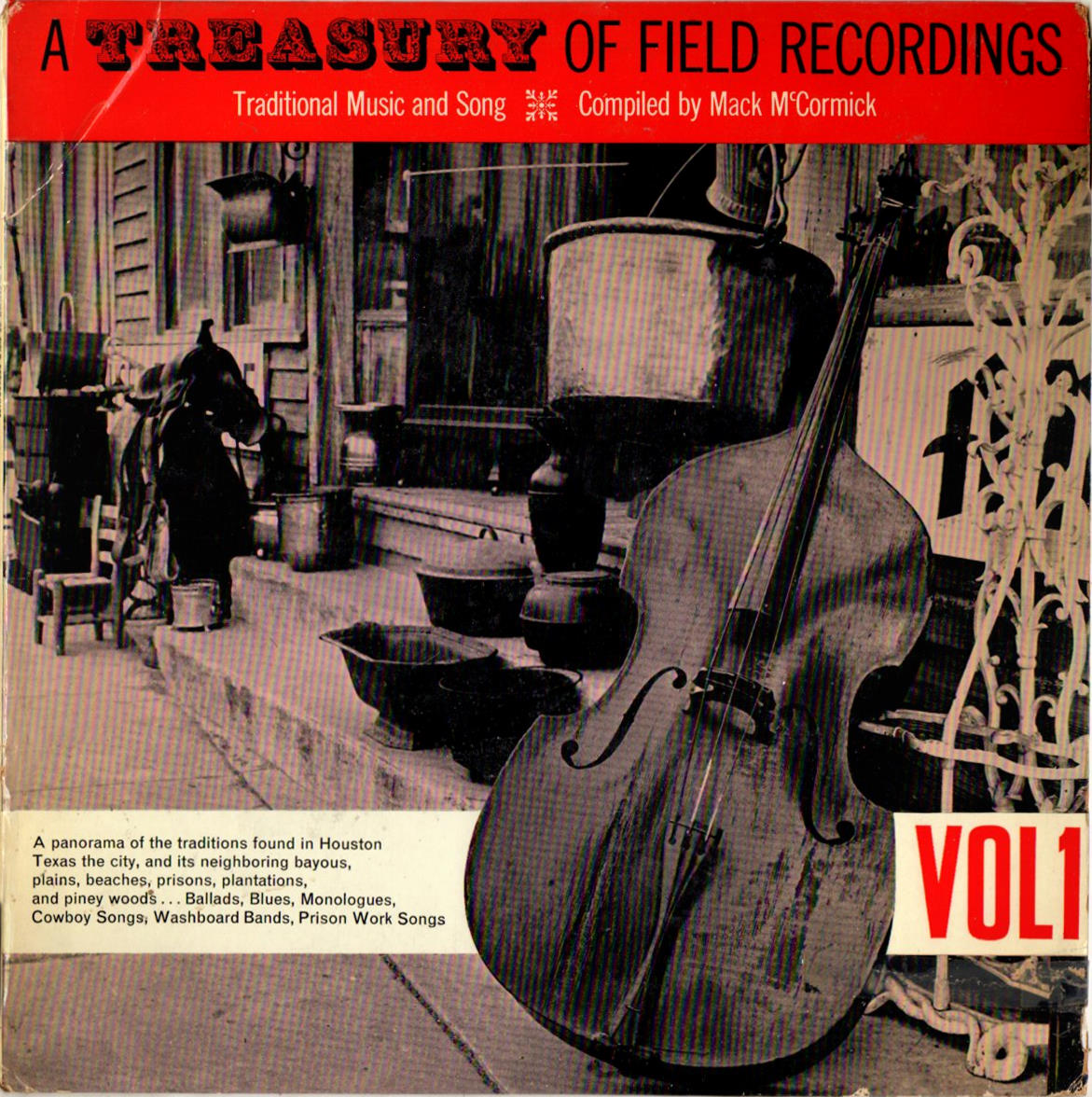

In 1960, he compiled and wrote booklets of scholarly notes for two albums entitled A Treasury Of Field Recordings Volumes 1 and 2, released by 77 Records in the U.K. It was testament to his determination and work ethic that the majority of the music was recorded by him.

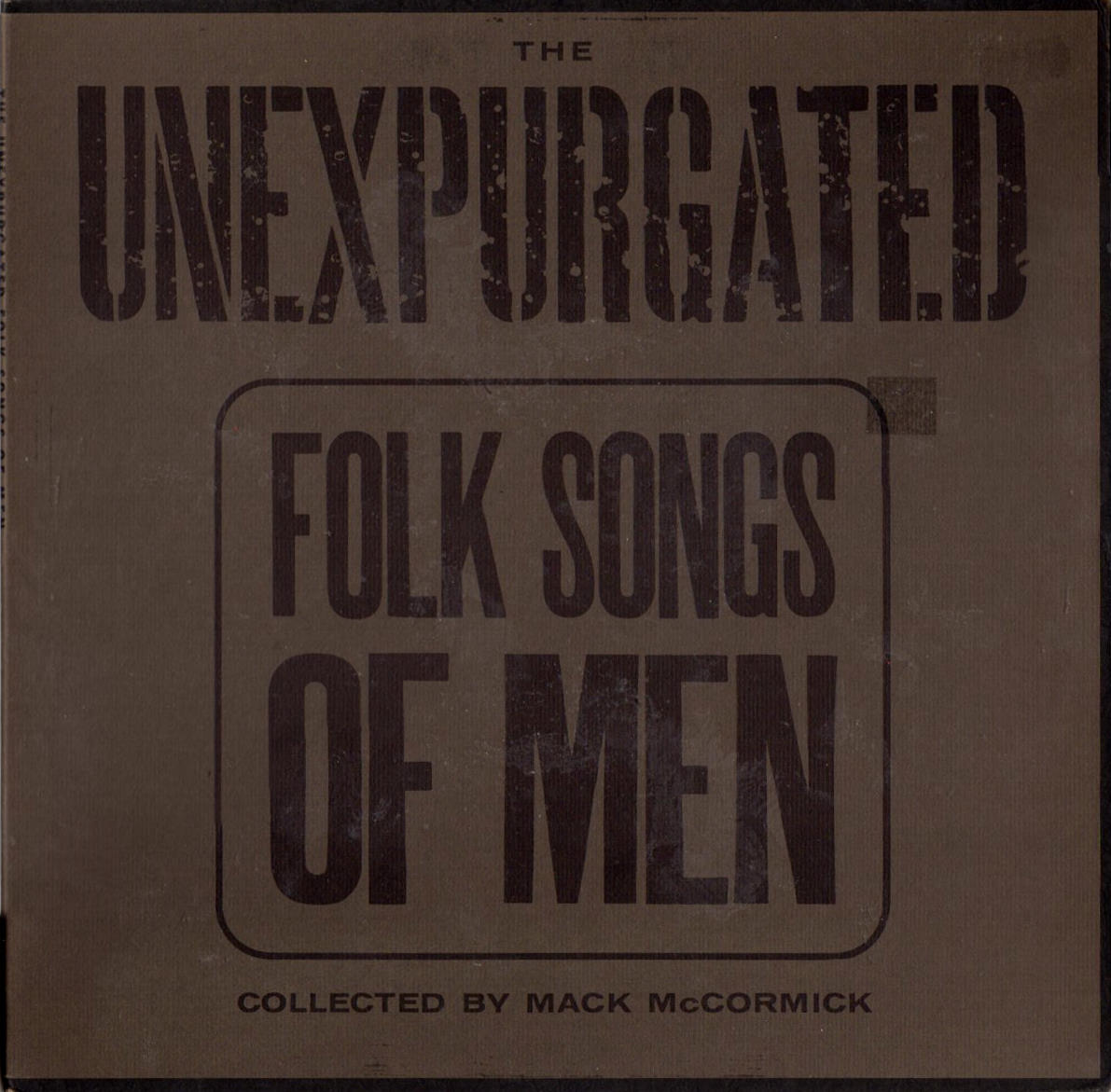

Also apparently, though information is scanty, McCormick's truly odd album, with the Monty Python-esque title, The Unexpurgated Folk Songs Of Men was issued in 1960 with no artist names and no record label name or address listed, though "Collected By Mack McCormick" is prominent on the front cover. The album included Lightning Hopkins, Mance Lipscomb, and recordings of McCormick, Paul Oliver, John A Lomax, Jr, and several other men in a state of extreme inebriation telling dirty jokes and singing bawdy songs horrendously out of tune. McCormick's sixteen pages of notes are an astonishing work of eccentric scholarship and ultra- serious, academic discussion of songs with titles like "No Balls All." His recounting of the history of the song "The Dirty Dozens" referencing blues songs, Richard Wright's Black Boy, the Bible, Roman law, Passover chants, and British folk songs before finding its origin in a poem used in the 19th century to teach Biblical facts to children, is masterful and could have been published in a folklore journal.

In 1961, He recorded Mance Lipscomb, and the recordings were released on the Reprise album Trouble In Mind with McCormick's poetic and evocative liner notes. When Lipscomb sang “Motherless Children,” McCormick, whose mother was dying in a hospital a few blocks away, began to weep. Lipscomb broke down and cried too, and the take was ruined.

McCormick started his own record label, Almanac, in 1966 and issued an album of his recordings of pianist Robert Shaw, one of the last living exponents of the Texas blues piano style. Included was a five page essay by McCormick, which was a wide ranging history of barrelhouse piano in Texas that offhandedly scattered enough revelations and brilliant insights to fill a book. Listed in the booklet as "To be released" were fourteen albums, including "Juneteenth," "The Sacred Harp," "Legacy Of Blind Lemon Jefferson," "The Negro Cowboy," "Zydeco, Gumbo & Cajun," "Folklorico Mexicano," and "Truck Drivers: Songs, Lore and Hero Tales." Unfortunately, none of these albums were ever released, and probably were never recorded. The list may have been the product of a manic episode. McCormick never released any of his recordings again.

In August 2023, Smithsonian Folkways issued Playing For The Man At The Door; 66 tracks of McCormick field recordings in a 3 CD or 6LP box set. Eighteen of the tracks had been previously issued on Treasury of Field Recordings Volumes 1 and 2, and the Robert Shaw Almanac album, all of which had been out of print for decades. The other 48 tracks include some previously unknown gems and other selections whose inclusion is puzzling.

Lightning Hopkins was the most well known and successful artist McCormick recorded and appropriately appears on nine tracks, more than any other artist on the set. Hopkins (1912-1982) became a wandering guitarist/ blues singer in his early teens, playing on street corners, in bars, and at parties. In 1946, he made his first recordings in Los Angeles, playing the same unadulterated Texas blues style he had been playing for two decades. Hopkins made dozens of 78s, many becoming jukebox hits in bars in Black neighborhoods. In Houston, his home base, he became a local celebrity and star attraction in the clubs and taverns of the Fourth Ward.

In 1959, Hopkins's life and career were to change dramatically in what must have seemed to him a strange, inexplicable, and unsettling way. Music writer and producer Sam Charters came to Houston and, probably with the help of McCormick, found Hopkins, recorded him, and in a chapter of his groundbreaking book, The Country Blues, referred to him as "the last singer in the grand style." This was completely, absurdly untrue, but it was great publicity. Before long, Hopkins, the heavily amplified electric guitar he had been using since the early fifties abandoned for an acoustic, was performing "folk blues" for white people.

Four of the Hopkins tracks were recorded by McCormick in 1962 at a Houston Folklore Group concert. Hopkins shows that he has learned well what appeals to the "folk blues" audience. He makes jokes, tap dances, and performs the corny, sentimental "Mr. Charlie," a long story about an orphan with a speech impediment who finds a home. He hasn't completely abandoned the blues and plays "Mojo Hand," with one of the irresistibly grooving boogie rhythms, he perfected during decades spent playing for dancers, and "World's In A Tangle," a topical slow blues with a mournful vocal and some dexterous guitar playing.

"Tom Moore's Farm," recorded in 1959, is one of the few blues that is explicitly a protest song. It's a powerful indictment of the sharecropping system and, specifically, Tom Moore, a real person who owned a 20,000 acres farm and used enforced prison labor. According to McCormick, Hopkins was extremely reluctant to record the song because he had been told by Moore never to sing it again. Hopkins had recorded the song before in 1948, but this version is longer, with an impassioned vocal sung over a repeating, ominous guitar riff. It's one of the greatest Hopkins performances and possibly the best track on the set.

"Blues Jumped A Rabbit," recorded immediately after "Tom Moore's Farm," has never been issued before, and it's hard to understand why. Hopkins's vocal is relaxed and bluesy, with a hint of humor sung over his near free form but still grooving guitar. "Corrine Corrina" is a very old song. Hopkins said, "It's older me twice." It's not his usual type of material and was probably sung in response to a McCormick request, but he sings it soulfully with insistently rhythmic guitar. The other two Hopkins tracks, "The Slop" and "Natural Born Lover," are negligible "Lightning's been drinking" throwaways. Hopkins was one of the most recorded musicians in blues history and made dozens of classic recordings. Of the tracks here, only “Tom Moore's Farm” and "Blues Jumped A Rabbit" are among them.

Mance Lipscomb (1895-1976) was probably McCormick's greatest blues talent discovery. In June 1960, he and Chris Strachwitz while knocking on doors, looking for Lightning Hopkins were told several times about a good blues singer in Navasota Texas. The Man At The Door booklet claims that Tom Moore told them to visit Lipscomb, which may also be true.

They found Lipscomb living in a two room cabin. He was sixty-five years old and had been a sharecropper for forty years until he took a job cutting grass on state highways. From age fifteen, he had played music on weekends at parties, bars, and dances, frequently for white people. His memory was phenomenal and his repertoire huge. Country music, gospel, pop music, dance tunes, the earliest blues to R&B tunes on the charts, like "The Night Time Is The Right Time," he played whatever people wanted to hear.

McCormick and Strachwitz recorded him immediately, focusing on the blues part of his repertoire. In a marathon session, Lipscomb performed twenty-three songs, thirteen of which made up his first Arhoolie album, Texas Sharecropper and Songster. McCormick retained the tapes of the other ten songs. Lipscomb's version of "Tom Moore's Farm," while using some stock verses, is still a powerful indictment of Moore with a pulsing, accusatory rhythm and he insisted that the song be issued anonymously on A Treasury Of Field Recordings because "… if he (Moore) knew I put out a song like that I couldn't live here no more…He got people out there that'd come in and set this house afire." "Casey Jones," never issued before, is a beautiful example of the breadth of Lipscomb's repertoire. It's his very personal version of a 1909 vaudeville song that Johnny Cash and many others have recorded. Though the lyrics tell a tragic tale, Lipscomb’s vocal is ironic, almost jivey while he plays a dance beat with his thumb on the bass strings while he picks swinging melodic variations with his fingers.

McCormick recorded Lipscomb at least three more times, apparently concentrating on the non-blues part of his repertoire. "God Moves On The Water," a gospel song about the sinking of the Titanic, was recorded by Blind Willie Johnson in 1929. Lipscomb uses the same melody and guitar part as Johnson but makes up his own seemingly improvised lyrics. Did he perform the song to satisfy a McCormick request? "Tall Angel At The Bar" is another gospel song that Lipscomb introduces by saying he learned it as a child, but it seems like an improvisation composed of snatches of various songs. "So Different Blues" is a Lipscomb original that features stunning guitar playing with a beautiful thumb picked bass line. Lipscomb recorded extensively for Arhoolie, but these tracks, especially “Casey Jones” and “So Different Blues,” are an important addition to his legacy.

R.T. Williams (1903-1996), aka The Grey Ghost, was a Texas blues pianist who began playing in the 1920s, traveled widely by freight train, playing the jukes, turpentine camps, and parties, arriving suddenly as if from nowhere and then vanishing. "…Just like a ghost. I come up out of the ground and then I go back in it,'" he told people. Grey Ghost never recorded in the 78 era, and the only other recordings of him were made in 1965, plus 4 tracks on a 1988 compilation and a 1992 CD. McCormick recorded him in 1964, and the two tracks included here are superb and an exciting surprise. "One Room Country Shack" is his version of Mercy Dee's hit record, which he follows closely but with his own eccentric time feel. "Little Red Rooster" has a great, sly vocal and lots of his unique right hand runs. The Smithsonian should issue the rest of McCormick's Grey Ghost recordings.

CeDell Davis (1926-2017) contracted polio as a child, severely limiting the mobility of his left hand and affecting his right. As a result, he developed a unique guitar style, playing with a knife in his left hand pressed on the strings. A few tracks of his playing and singing were issued on various country blues compilations in the 1980s, but a complete CD was not issued until 1994. McCormick recorded him in 1969, and the three tracks included on Man At The Door are downhome, juke blues classics with Davis's plain spoken vocals and knife slide playing over a boogie-ing second guitar. Rough, crude, and glorious blues. Smithsonian---give us more!

Hop Wilson (1921-1975) had an extensive recording career before McCormick recorded him live, accompanied only by drums in a Houston club in 1966. He played a double neck steel guitar with no country influence, just straight up blues, sounding a bit like Elmore James. "3 O' Clock Blues" is patterned after BB King's hit, with Wilson's rough, mournful vocal and a wild guitar solo. "Broke And Hungry" is a deep, hopeless blues. Wilson's vocal is soulful storytelling with another beautiful guitar solo. The bar room is raucous. People yell encouragement and appreciation at Wilson's best licks. This is a great live blues recording, and if there is more, it should be released.

Robert Shaw (1908-1985) was one of the great Texas blues pianists. In McCormick's words, "He was one of the Santa Fe group who rambled between Fort Bend County's Brazos River bottoms and next door Houston's Fourth Ward, singing these blues, playing these stomps and belly rubs for sweaty crowds who moved in response to his fingers, soaked up by the hard blues a workingman likes to hear." When McCormick recorded him in 1963, Shaw had not lost any of his technique or modernized his style. "Someday Baby" is a masterpiece of blues piano, and that it remained unheard for sixty years was a loss we are now fortunate to know we suffered. "Put Me In The Alley" and "The Clinton" are also great blues playing, but the piano is dreadfully out of tune.

Buster Pickens (1916-1964) was another Texas blues pianist who worked the same circuit as The Grey Ghost and Robert Shaw. In 1960 and 1961, McCormick recorded him playing and singing in his deep, melancholy voice. The three tracks included on this set are previously unreleased and great examples of Texas barrelhouse piano in the 30s, and "Shorty George" is particularly moving.

Andrew Everett (1892-1967) was born a year after Charlie Patton and a year before Blind Lemon Jefferson, which puts him in the first generation of blues singers. On "Hello Central," his style is archaic, proto blues; droning vocal, one chord vamp, non-rhyming stock verses, flexible meter with a hypnotic rhythm. "K.C. Ain't Nothing But A Rag" isn't a rag but a probably improvised instrumental that has a flowing dance groove with some surprising counter rhythms. Everett sounds like Patton and Jefferson might have sounded before they got modern and sophisticated.

R.C. Forest and Gozy Kilpatrick were a guitar/harmonica duo that played on the streets. Forest was a limited but very effective singer and a serviceable guitarist with a strong rhythm. Kilpatrick was a fair harmonica player in the Sonny Boy Williamson #1 style. "Crying Won't Make Me Stay," propelled by the "Catfish" rhythm, has a dark, ominous feel. Forest does a solo street corner, Lightning Hopkins style cover of Lowell Fulson's "Black Widow Spider" and forgets the last verse. "Tin Can Alley Blues," despite the booklet notes, is not a version of Lonnie Johnson's song but apparently an original song with dark, morbid lyrics and a despairing vocal to match. All the Forest and Kilpatrick songs are slow to medium blues with sad lyrics. It's hard to believe they could earn money on the streets with such depressing fare, but it's a powerful listening experience.

Dudley Alexander and His Washboard Band was a zydeco group and a very rough, downhome one that sounded much more rural than Clifton Chenier, who was taking zydeco to the R&B charts at the time. Their version of "St James Infirmary" bears little resemblance musically or lyrically to the jazz standard and has intonation issues. Still, the 2/4 dance rhythm is strong, and it's a glorious, "2 am and everyone in the place is drunk" mess.

Joel Hopkins was Lightning's older, less talented, charismatic, and funny brother. His voice was rough and his guitar playing less fluid and rhythmically cruder. He plays "Matchbox Blues" and "Good Times Here" at the limit of his ability, continually on the edge of musical disaster. They're exciting performances.

Blues Wallace was a guitar, harmonica, and drums one man band who worked in San Antonio. His take on Bobby Bland's "It's My Life Baby," recorded live in a club in 1966, is an impassioned performance, vocally sounding a bit like John Lee Hooker with some exciting Freddie King style electric guitar.

Most of the rest of the tracks on the set are by lesser talents and range through various gradations of mediocrity---moderately enjoyable one time, interesting historically, but not very good, OK but generic, good but have heard it done much better. The compilers did make some missteps. Three pieces by "Bongo Joe" George Coleman, including one that is nine minutes long, is too much, and what was slightly amusing becomes "stop with that damn oil barrel” tedium. Jimmy Womack was a white country/folk singer for whom McCormick had an unaccountable admiration, apparently shared by the compilers. His tracks, "Talking Blues" and "Atomic Energy," are competently performed but not particularly distinctive and not as charming or amusing as both Womack and McCormick seemed to think they were. Hardy Gray's "Come And Go With Me To That Land" is marred by his wandering pitch and is difficult listening at over five minutes long. "Runaway," a nondescript 12 bar blues in D, is a bit better, but he never impresses as much more than a front porch singer. Not every blues singer that McCormick recorded is worthy of a deluxe box set issue. The recording of Joe Patterson playing the quills is only of historical value or maybe only curiosity value. Two pieces, a recording of a medicine show pitch and one of an auctioneer, are not music and boring, but thankfully short.

Both the Playing For The Man At The Door CD and LP sets include a 128 page 12 ½ "x 12 ½" booklet with short bios of all the artists and notes on the individual tracks and many nicely reproduced black and white photos, most never published before. There's also a painfully honest remembrance of McCormick by his daughter and four articles; an informative historical overview entitled "African Americans And The Blues In Texas" by Mark Puryea, a biographical essay "The Man At The Door" by Jeff Place and John W Troutman, and another one on McCormick's research methods and the importance of his archive "The Collection" also by Place and Troutman, and finally, "Thoughts On Mack's Collection" by Don Flemons.

The booklet articles on McCormick by Troutman and Place discuss in detail his mental illness, difficult personality, and misdeeds, but are notably lacking in the just and balancing praise due for the accomplishments of a man who grew up in difficult circumstances, never graduating high school, but managed, because of his near unbelievable dedication and hard work, while suffering from serious mental illness and without significant financial assistance from academic or government institutions, to discover and document just about all we know about some of the most important artists of African American music in the twentieth century. That McCormick was a talented writer and self-educated folklorist whose album liner notes display an original, wide ranging, and brilliant intellect is unmentioned. That he was a great record producer with the can't-be-learned ability to bring out the best in artists and recognize talent is also unmentioned.

The Playing For The Man At The Door LP box is sturdy. The LPs come in printed outer jackets and quality poly lined inner sleeves. My LPs were glossy and unmarked, but all slightly warped. They played well, without skipping. The pressings were quiet.

The booklet provides no information on McCormick's recording equipment, but the notes to his Almanac Robert Shaw LP state that an Ampex 354 and Telefunken microphones were used. The recordings are all mono, and with a very few, not so bad, exceptions, are excellent sonically. McCormick had a good ear and cared about sound quality. Voices are especially well recorded, and the balance is always good. The Hopkins live recordings are audiophile quality.

Ronnie Simpkins at the Smithsonian is credited in the notes for analog to digital transfers and the magic words “all analog mastering” are missing, so we can assume that the LPs were cut from digital files. There is also a credit for "audio restoration," which probably means tape de-hissing. The sound quality was quite good, non-fatiguing digital. Dynamics were realistic and uncompressed. Treble was extended but not harsh. Some "air" and analog smoothness were missing, but not so much as to be an irritant. I have not heard the CD version of Playing For The Man At The Door.

Playing For The Man At The Door includes some of the greatest blues music recorded in the last 60 plus years and is the most important release of vintage blues in a very long time. This box set is highly recommended to anyone with an interest in blues, American roots music, or whose mind is open and ready to travel to a time and a culture that is thankfully long past, and to sit and listen with humility and gratitude to the music of the people who lived there.

________________________________

Some of the quotes above were taken from Michael Hall's excellent article, "Hellhounds on his Trail: Mack McCormick's Long, Tortured Quest to Find the Real Robert Johnson, " published in Texas Monthly in May 2023 which is an invaluable source of information on McCormick's later years.

Copyright 2023 and all right reserved by Joseph W. Washek