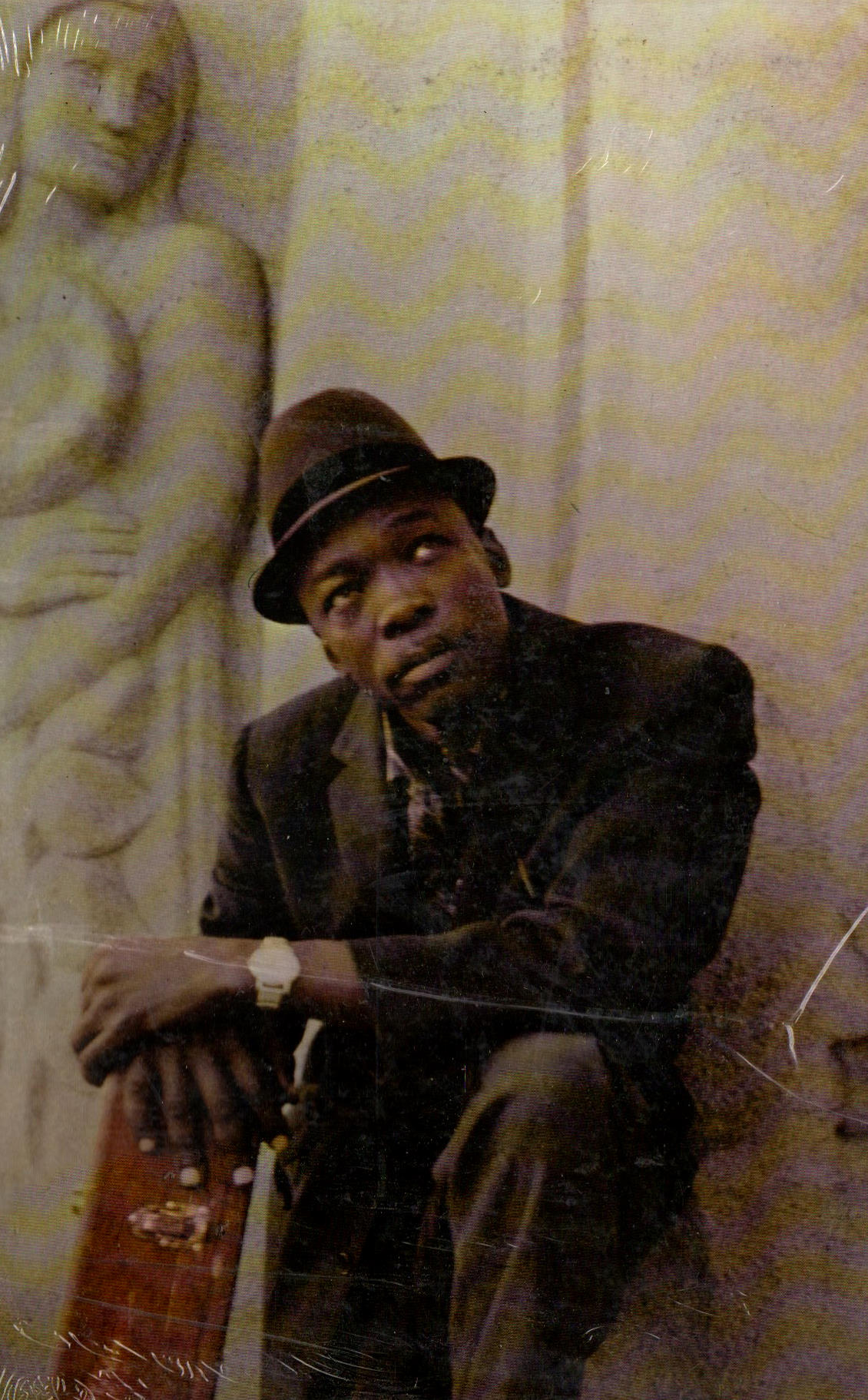

John Lee Hooker "Burnin'" Reissued by Craft Records in Stereo

Hooker meets the Motown Funk Brothers

In 1961, John Lee Hooker recorded "Burnin’", an album accompanied by an early version of Motown's legendary Funk Brothers band for Vee Jay Records in one session, probably four hours in length. Vee Jay was an independent label based in Chicago, owned by an African American married couple, Vivian Carter and James Bracken, which had achieved considerable success selling R&B, blues, gospel, and jazz records to Black audiences. Hooker had been recording for the label since 1955, and in 1958, one of his Vee Jay 45s made the top 30 on the R&B chart. In 1960, another one did even better and peaked at #21.

A John Lee Hooker record on the R&B chart in 1960, more than eleven years after his first appearance there, was surprising, if not amazing. His music sounded nothing like the proto-soul of Jackie Wilson, Jerry Butler and Hank Ballard, etc., dominating the chart at the time. Hooker (1912?-2001) was probably close to fifty years old, had been recording since 1948, and was, with the possible exception of Lightnin' Hopkins, the most musically archaic "down home" blues artist to be commercially successful with the Black audience after the 1930s. It was a testament to the production acumen and marketing skills of Vee Jay that he could sell records and be on the charts at the same time as the Everly Brothers' "Cathy's Clown" (yes, it was an R&B #1 hit in June 1960) and the Drifters' "Save The Last Dance For Me."

Hooker's music was blues and not pop or R&B or jazz or soul influenced, but rooted in the earliest blues and pre-blues field hollers. It was extremely basic but also free. His songs used the simplest of blues structures--frequently one chord vamps. Often, he would not follow the I-IV-V blues form of the tune but would repeat or omit a chord. His vocal melodies were cliched and rudimentary-- two or three notes or, sometimes, one. "Talking blues” was almost an accurate description of his style. He pitched his voice in the area of one note, and then it was just blues sprechstimme and grooving guitar. His sense of meter was wayward. A twelve-bar chorus would be followed by one of ten bars and then one of eleven. His guitar would go off on rhythmic tangents.

Hooker's "free blues" style was not about songs as much as it was about "Hooker being Hooker" and expressing himself. If the words he wanted to sing didn't fit into twelve bars, he'd play fourteen. If he played a lick on the guitar and it didn't fit the underlying chord change but felt "right," it was "right.” Needless to say, he was extremely difficult to accompany, and until 1955, he almost always recorded alone or in duo with the great guitarist Eddie Kirkland. Hooker said, "Back when I was younger coming up, I was playing more hard blues by myself. I could play more guitar and do more by myself. I had no band to interfere. I could do what I wanted to do when I wanted to do it."

Hooker told stories, complained, or spoke about whatever was on his mind over a dance beat the way today's rappers do. Like Patton, House, and other early bluesmen, he could play "songs" in juke joints for an hour or more by singing stock or spur of the moment lyrics while keeping the groove rocking. His art was improvisatory. He did not use the usual two repeating lines followed by the third rhyming "punch line" structure. His lyrics lacked discernible meter and rhymes were accidental. Most of his songs were not really "songs" at all but were musical and lyrical improvisations on a theme or mood. He would sing a line that stated the theme and then follow it with stream-of-consciousness variations that could even include snatches of other songs. When a song became a hit, he would repeat it at shows more or less like the record.

Such a minimalistic style should have been boring, and Hooker could have spent his life playing and singing on his porch after a hard day working in the fields, but he possessed one of the greatest blues voices. It was deep, menacing, limited in range, and almost tuneless but had a unique, immediately identifiable sound that compelled one to listen. He was also a rhythmic genius who created the "John Lee Hooker boogie." Hooker could hear a rhythmic pulse in his mind or feel it in his body and beat it out with his stomping foot, while superimposing, with his guitar, other rhythms over it, creating complex but danceable polyrhythms. But unlike the pre-war Mississippi blues greats, Hooker used an electric guitar cranked to the point of distortion. The sustain and volume offered by amplification allowed Hooker to play, with slashing ferocity and his own Delta blues feel, heavy, pile driving, boogie rhythms like the ones of Louis Jordan and the big bands of Basie and Hampton.

In 1948, Hooker recorded, accompanied only by his guitar, "Boogie Chillen," a hard rocking dance tune that is really just a groove over which Hooker raps and semi-sings about one of the great rock 'n roll themes-- the right to party. It was to be the template for all of his music and the beginning of a more than fifty year career. "Boogie Chillen" made #1 on the R&B charts in January 1949. He had two more records that went to #8 and #11 the same year, which repeated the voice and boogieing guitar formula.

Now Hooker was one of the biggest stars in Black music, and despite his records being immediately identifiable, or maybe because of it, he began recording for many labels under pseudonyms, some not so pseudo. He was; "John Lee Cooker," "John Lee Booker," "John Lee," "Johnny Williams," "Delta John," "Texas Slim," "The Boogie Man," most fantastically, "Birmingham Sam and His Magic Guitar" and most bizarrely, "Little Pork Chops." Between 1949 and 1959, he recorded close to 400 songs.

His records were mainstays on jukeboxes in Black neighborhoods, and he worked in clubs with names like "Henry's Swing Club," "Huddy Color Bar," "Club Carribe," and "Harlem Inn." The main audience for Hooker and "down home" bluesmen in the late forties was Black people who had come north in "The Great Migration" and wanted to hear the rural music they had grown up with. By the mid-fifties, the blues audience was shrinking. Young Black people associated blues music, especially solo country blues, with the life of Jim Crow oppression in the Deep South that they had escaped from and wanted to forget.

In 1955, Hooker, always ambitious and a canny businessman, knew that if he wanted to continue to have a career in music, he would have to reinvent himself or at least seem to. The companies he had recorded for in the fifties were all owned by white people and aimed his records at middle aged and older Black people. Vivian Carter, the "V" in Vee Jay, and her brother Calvin, who were the main creative forces of the company, were Black and 34 and 30 years old, respectively. They knew how to sell records to young urban Blacks and had made Vee Jay a presence on the charts with R&B hits by vocal groups. In 1955, they recorded another Mississippi bluesman, Jimmy Reed, doing up tempo, danceable blues tunes, and the result was more than a dozen R&B hits in the next six years. Hooker wanted that type of success and began recording for Vee Jay.

In 1958, Vee Jay got Hooker back on the charts by putting an R&B styled band behind him and recording a pop inflected tune called "I Love You Honey", not written by Hooker. The cliched, rhyming lyrics, the unimaginative melody, and the conventional accompaniment made the wild and often weird Hooker seem almost bland. Almost but not quite, because despite making his best effort to not sound like John Lee Hooker, his voice is still dark and ominous. Saccharine love songs were not his forte.

In 1960, he had another chart record for Vee Jay, "No Shoes," which had to be one of the more unlikely R&B hits of the era. It's a 12 bar blues with a 12/8 feel accompanied by a band. This is not a love song, and Hooker is back to his incorrigible self. That means "John Lee's time is the right time," and he throws in a few extra beats. The band sounds confused and it's easy to imagine their eyes meeting nervously. "What's he doing next?" It's a typical Hooker improvisation reined into shouting distance of conventionality by the presence of a band. With lyrics like, "No shoes on my feet, and no food to go on my table. Oh, no, too sad. Children crying for bread," it's hard to imagine the record got much jukebox play on Saturday nights. Somehow, the record became a minor hit. Vee Jay's promo people must have been extremely charming.

In 1960, Hooker appeared at the second Newport Folk Festival. Soon he was playing clubs with names like "The Golden Vanity," "The Second Fret," "The Fifth Peg," and "Gerde's Folk City." Later that year, Vee Jay and Hooker released an album deceptively entitled, The Folk Lore of John Lee Hooker. There were no folk songs on the record. It featured two songs recorded live at his Newport appearance and was a clear attempt to market him to the collegiate folk audience. The other ten songs, recorded before Newport, were Hooker playing no compromise Hooker style blues. One would suspect that the reactions of adventurous Kingston Trio fans who bought the record ranged from perplexity to outrage.

At this point, it would have been commercially sensible to build on his "folk" momentum and rush out an album of Hooker singing actual folk songs while eliminating or at least toning down his Hook-centricities. But Hooker was not that type of artist, and Vee Jay was not the type of label. Instead, he recorded Burnin', which was, if not totally unadulterated Hooker, still a blues album. It included "Boom Boom," his biggest hit for Vee Jay and probably his most famous song.

The circumstances of the recording of Burnin' are mysterious. Neither the liner notes nor the Blues Records 1943-1970 discography lists any recording or musician information. However, online sources show a November 1961 recording date in Chicago and an early edition of Motown legends, The Funk Brothers, as the backup band.

The Funk Brothers were an odd choice to back Hooker. They were all technically accomplished musicians from a jazz background, between thirteen and twenty-eight years younger than him, that were doing studio work by day at Motown, reading charts and playing them to perfection, while playing hip modern jazz at night. They had never recorded with anyone like Hooker.

It was also odd that six musicians from Detroit would be hired to do a blues session in Chicago, where there were hundreds of blues musicians. The only reasonable explanation seems to be that Hooker, who moved to Detroit in 1943 and reportedly lived there until 1970, personally chose them to slick up his sound, get some new dance beats, and maybe some radio play.

The album starts with the all time classic "Boom Boom." It went to #16 R&B for Hooker and broke into the Billboard Hot 100. A few years later, the Animals had an even bigger hit with the song. It was a rock cover band standard throughout the 60s. Hooker sang it in probably the greatest blues performance in a Hollywood movie-- the Maxwell Street scene in The Blues Brothers. It's been covered by artists as diverse as Donald Byrd, the Oak Ridge Boys, and Mae West. The song is a perennial entry on the Rolling Stone 500 Greatest Songs list.

It's a song, and that's what's special about it in the Hooker canon. The lyrics, while not rhyming, are coherent and scan. Hooker keeps strictly to the I-IV-V form, making it a lot easier for the band to relax, dig in, play tight and rock the way they did at Motown.

The song is propelled by a great guitar riff and the rhythm is one of the greatest "shake your butt while waving a beer bottle” grooves of all time. Here, maybe the best bass-drums team ever, the funkiest of the Funk Brothers--Jimmy Jamerson and Benny Benjamin-- do what they do and get into that pocket that few others could get into and then play hip, swinging, and, yes, funky. Hooker's music had never sounded so sophisticated and danceable before. The arrangement with the stop time and the boogie section is brilliant and unusually complex for a Hooker song. Did the Funk Brothers work it up in the studio? Hooker's vocal is a superb mixture of his usual menace and a dash of humor. "Boom Boom" is the new 1962 model John Lee Hooker, an up to date, urban, Jimmy Reed style bluesman.

With "Process," the old Hooker is back, complaining about a woman spending all her money on hair straightening products. -------------------That was an uncomfortable silence. Hmmmmm. Let’s move on. The words seem improvised. Hooker can’t seem to decide how the melody goes. The band seems like they are just vamping and trying to follow Hooker. At one point, he breaks the I-IV-V form and hangs on the I. The Funk Brothers seem discombobulated, the piano seems to go to IV momentarily, but they stay with Hooker.

"Lost A Good Girl" is a medium tempo boogie, and the band, riding on Jamerson and Benjamin's solid groove, seems more comfortable. It's not much of a song, though.

On" A New Leaf," Hooker tries, not very successfully, to improvise a song about reforming and abandoning his bad habits. When he stays on the IV, and they go to the V, the band seems completely at sea. At this point, the Funk Brothers had to be realizing that studio work under the direction of the perfectionist Berry Gordy, was no preparation for a Hooker session.

"Blues Before Sunrise" is Hooker's version of Leroy Carr's 1934 song. This is the type of deep blues he excelled at, and his vocal is impassioned. There's a prepared arrangement with some nice backup riffs by the saxes and a very good T-Bone Walker style guitar solo by Larry Veeder. It's an excellent performance by all and probably, after "Boom Boom," the best thing on the album.

"Let's Make It" is another of Hooker's "Boogie Chillen" rapping dance pieces. Accompanied only by his guitar, Hooker could always play his funky boogie rhythms and jive talk to create an entertaining jukebox record. But here with the Funk Brothers, who can't seem to find a groove, he seems ill at ease. The plodding rhythm makes the repetitive lyric and monotonous melody all too obvious.

"I Got A Letter" is another Hooker improvisation over the band vamping cautiously with a 12/8 feel. Their caution was well advised. Near the end of the song, what was apparently intended to be a 12 bar instrumental interlude turns into a train wreck. Veeder, the other guitarist, begins a solo, but Hooker begins to solo also. Veeder stops, and then Hooker does as well. The pianist, unsure what is happening, begins to solo. Hooker comes in early and begins to sing another chorus. The engineer mercifully fades the track before the inevitable second musical train wreck.

On "Thelma," the Funk Brothers decide that the way to deal with Hooker is to ignore him and his hijinks and just play the form doggedly over and over. The result is a bit like blues karaoke, but it's an effective tactic. Hooker's vocal is shouting and passionate.

"Drug Store Woman" is Hooker complaining about a woman again. This time the unfortunate lady's habit of spending her money on "lipstick and powder, all that kind of stuff" at the drug store has aroused his, all too frequent, ire. For a guy who earned his living in bars playing songs about partying and casual sex, Hooker (at least in his songs) espoused exceedingly puritanical standards for female behavior. But I'm a music writer, not a psychologist, so I will confine myself to observing that Hooker begins the song by playing blues guitar cliché lick #1, and musically things don't get better.

The riff from the Champs' song "Tequila" is the basis of "Keep Your Hands To Yourself." The Funk Brothers seem overjoyed to be playing a song with a definite melodic structure and tear it up. Benny Benjamin's Latin/funk beat on this track is joyously danceable. Hooker does one of his free form, melody free raps but seems to get stuck for words after two choruses and lets the band play. That's a good thing.

"What Do You Say" is powered by Jamerson's bass playing the hypnotic Mississippi Hill Country blues rhythm figure from the song "Shake' Em On Down." The band sounds tentative, like this is their first try at the song. They lay down a static and a bit square dance groove, and we're back to blues karaoke. Hooker improvises some incoherent lyrics and, by the end, is telling us "To do the twist."

Burnin' is mostly a musically poor album redeemed by a few good tracks and one song that is an unqualified success and a near masterpiece—"Boom Boom." The Funk Brothers were talented jazz and studio musicians who excelled at playing songs creatively, but their talents were hemmed in by Hooker and his by them. He gave the Funk Brothers little to work with. His improvisational "songs" were so harmonically and melodically simplistic that the ideal and maybe only effective way to perform them was Hooker alone with his guitar, which allowed free rein to his rhythmic genius.

Possibly, if there had been some rehearsals and gigs, the band might have become more accustomed to Hooker's eccentricities and put together some arrangements. But that was not to be. Burnin' was recorded in one day, probably at a standard four hour studio session. Most of the album documents the uncomfortable attempt by Hooker and the Funk Brothers to find a way to play music together. They never really succeeded except for "Boom Boom."

Craft Records recently reissued Burnin’, "Newly remastered from the original analog tapes by Kevin Gray at Cohearent Audio, pressed on 180-gram vinyl and housed in a tip-on jacket." The records were pressed at Memphis Records Pressing.

My copy of the record is flat and plays very quietly. It came out of the archival quality sleeve, bright, lustrous, and unmarked. It is an excellent pressing. Thank you to Craft for the archival sleeve. We record collectors appreciate nice sleeves.

Mastering, as we have come to expect from Kevin Gray, is excellent. The sound is warm and well balanced with a full, almost tactile midrange. Hooker's voice is nicely reproduced, especially the bottom end, which has an attractive resonance. Benny Benjamin's drums have impact and power. It's an intelligent and tasteful remaster.

But the mastering is in stereo, and that is a major problem. The stereo separation is completely artificial with the dreaded "hole in the middle." For most of the album, the horns, Veeder's guitar, and the drums are clustered in one channel, with bass and piano slightly toward the middle and Hooker's voice and guitar in the other. The soundstage layout varies throughout the LP, and Hooker's voice and guitar are sometimes in different channels. The overtones and reverberation of a band playing in a room are missing as is the excitement of listening to a great band play together. The sound is disjointed and made me frustrated. I would not say the album is unlistenable, but now that my obligation to Tracking Angle's readers has been satisfied, I doubt I'll ever play it again.

I have never heard an original stereo copy of Burnin'. I have no doubt that the Craft LP accurately reproduces the separation of the stereo tape, which was probably recorded two track. I wonder if anyone at Craft listened to the stereo tape before deciding to use it for the LP reissue.

I own an original mono copy of Burnin'. In comparison to the reissue, the mono sounds a bit congested and slightly muffled. I think Kevin Gray's remastering has a smoother, more natural tonal balance. The original's midrange is slightly thin, and its treble a bit harsh. The remaster has a more extended dynamic range and the instruments sound clearer and more defined.

All that is true but all less important than the fact that Hooker's voice sounded bigger and wider, center stage, between the speakers in mono. That is as it should be, his voice is the focus of the recording. Behind him, the instruments in mono sounded natural, like a band in a club. I preferred the mono mix even with its shortcomings to the badly flawed stereo mix of the reissue by a wide margin.

There are many better Hooker albums than Burnin'. Almost all the ones which feature him playing electric guitar solo are better. As much as it pains me to do so, I would advise anyone who wants to acquire Burnin' whose budget does not extend to a pricey mono original, to buy the expanded digital edition, which includes the mono mix.

Copyright 2023 and all rights reserved by Joseph W. Washek.