When James Bond Met Two Beatles...

LaLa Land Records' Deluxe Reissue Revisits How Paul McCartney and George Martin Re-Invented the James Bond Sound

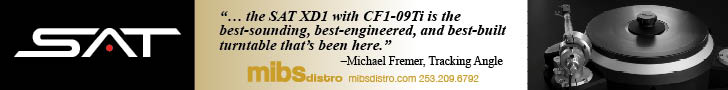

John Barry with his then wife Jane Birkin in their E-Type Jaguar, London 1960s

John Barry with his then wife Jane Birkin in their E-Type Jaguar, London 1960s

How Music Gave James Bond His Mojo

“Bond. James Bond.”

Are there any three words more iconic in the history of cinema? The scene in which we first hear them in Dr No (1962) takes place in an elite gambling club in London, and are spoken by Sean Connery in response to an unlucky-at-cards bombshell seated across from our hero at the gaming table. The lady in question is quickly finding her losing streak of less interest than the mysterious stranger dealing her the cards. And so, with one coyly raised eyebrow, she inquires after his name.

“Bond. James Bond,” comes the reply.

In this now almost mythic introduction to Connery’s OG screen incarnation of Ian Fleming’s already internationally popular spy hero, everything about how director Terence Young sets up the scene - revealing Bond first from behind, followed by his hands tapping out a cigarette from his bespoke silver case, then finally giving him the head-on medium shot as he lights up and meets the lady’s gaze - is perfectly gauged to establish both Bond’s casual, devil-may-care, dangerous attraction, and jump start the mythology of “James Bond”.

But, I would argue, nothing about the scene would have the impact it does without the quiet underscoring of John Barry’s iconic “James Bond” Theme (adapted from a tune by the film’s titular composer, Monty Norman) that steals in the moment we get our first view of Sean Connery - all smoldering danger, insouciance, and sexual allure in equal measure.

That “James Bond” Theme - now one of the most famous pieces of music ever written and recorded - was essentially an afterthought, added well into post-production by producers Albert Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, who realized their screen hero needed some extra musical “oomph” to make him leap off the screen. John Barry, already a well-established composer for the small and big screen, and a hitmaker with his jazz combo “The John Barry Seven”, was the perfect choice to arrange Norman’s not particularly distinctive theme, lifted from a stockpile of old manuscripts of unused material. Barry’s arrangement not only set the musical tone for the movies to follow (the majority of which he went on to score) but established the musical stylings which helped define the 60s sound every bit as much as did the records of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

The story of how the James Bond theme came into existence is actually very complicated, and resulted in a long-running legal action between Barry and Norman. Vic Flick, the guitarist on this seminal track (chosen because he had already worked with Barry on an earlier hit soundtrack, Beat Girl - 1960), summed it up this way: “I would say it’s part Monty Norman’s talent, John Barry’s and mine, all put together. When you hear it, you know it’s a James Bond movie.” I actually got to hear Flick play the theme live at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Goldwyn Theater here in Los Angeles in 2012, part of an evening celebrating Bond music.

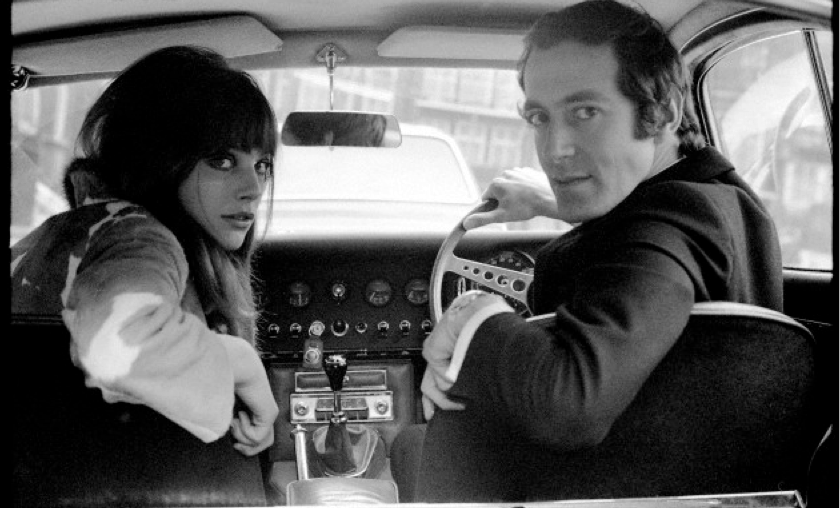

The host of that evening was Jon Burlingame, the indispensable film music critic and chronicler for Variety, and the author of the essential book, The Music of James Bond, in which the history of the Bond theme is covered in greater detail than is warranted here.

Jon Burlingame, Film Music Critic for Variety, and author of the sleeve notes for the LaLaLand release of Live and Let Die

Jon Burlingame, Film Music Critic for Variety, and author of the sleeve notes for the LaLaLand release of Live and Let Die

That evening at the Academy, and watching any Bond film, is a vivid reminder that for all the brilliant conception, imagination and execution of the Bond films, they are one of the foremost examples of how important - nay, essential - music is in the creation of a compelling cinematic world that reaches far beyond the screen itself into the popular culture and imagination. I would argue (and many would agree) that without that iconic James Bond Theme (and the John Barry scores that followed), the film series would have had nowhere near the worldwide success and ongoing resonance it gained. That music defines a mood, a period, an attitude, a sense of danger and fun, that is so resonant we only have to hear a few bars to be transported into a world apart.

Of course, as the film series progressed, both Barry and his successors then had the enormous challenge of at least matching and hopefully surpassing the musical expectations of any Bond audience, and it’s fair to say that this challenge was unequally met in the films that began with Roger Moore’s assumption of the title role. One of the better examples of how a composer and song writer other than Barry met that challenge is under consideration here, in the score for that first Roger Moore film, Live and Let Die, composed by the fifth Beatle, Georg Martin. (And a later Barry score for Octopussy, also just given the LaLaLand Records’ deluxe treatment, will be covered in a separate review).

For all their many virtues, neither Live and Let Die (1973) nor Octopussy (1983) reside in the top tier of Bond scores (or Bond films, for that matter). However, that isn’t to say there aren’t many musical delights and surprises to be had from listening to these CDs, and I for one am very grateful that LaLaLand Records has given us these comprehensive overviews of these scores.

Fortunately, Jon Burlingame is on hand to provide the superb notes for this pair of releases. Once again, boutique film and TV music label LaLaLand Records proves it is the leader in the field of soundtrack reissues with these immaculately presented and annotated 2CD sets which will be essential purchases for Bond fans and film music completists alike, even if they have the original vinyl albums. (LaLaLand has already issued definitive expanded editions of several of the later David Arnold Bond scores, themselves amongst the very best non-John Barry Bond soundtracks). Yes, there are shortcomings in the music itself, and sometimes the sound, shortcomings I will go into during the course of my reviews, but these are largely intrinsic to the scores and their original recordings, and therefore beyond the control of LaLaLand to fix.

So without further ado, let’s dive into the Bond sound as it was reinvented for Roger Moore’s first outing in the title role, courtesy of George Martin and a certain Beatle……

Barry and Beyond: Re-Imagining the Bond Sound

Forgive me if I begin with some personal reminiscences here. The Bond movies, their music, and the soundtrack for Live and Let Die hold special resonance.

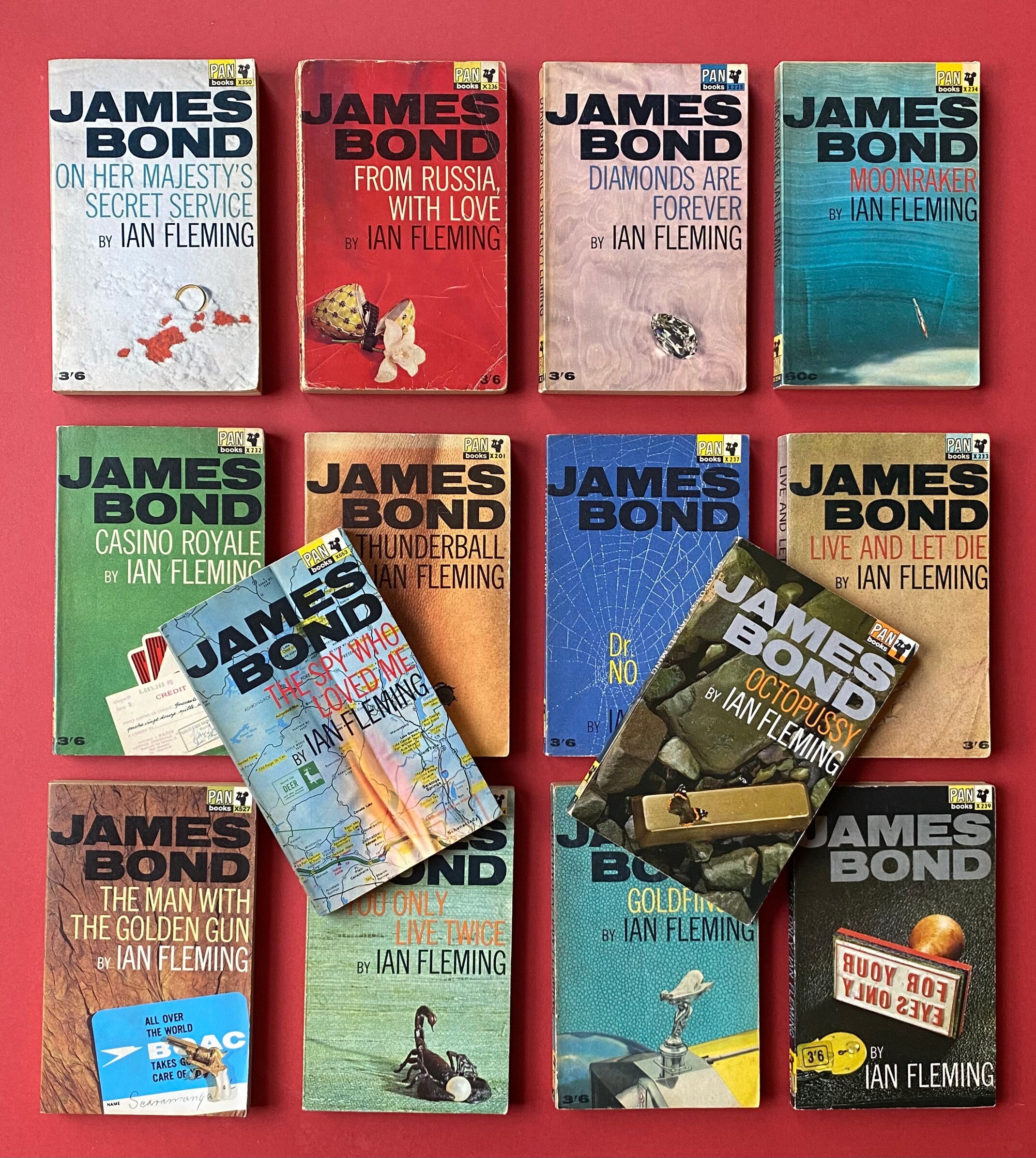

Like so many men of his post-WW2 generation, my father’s imaginative life was hugely colored by the emergence of Ian Fleming’s series of Bond novels that began with the publication of Casino Royale in 1953, when he was 28. Well-thumbed paperback copies not only adorned his bedside table for as long as I can remember, they accompanied him on all his own adventures to the Himalayas, the only books - as far as I know - he took with him. (These 1960s paperback editions were, in their own way, every bit as cool in their design as the artwork for the hardback first editions).

One of my favorite designs - note the bullet holes in the cover

One of my favorite designs - note the bullet holes in the cover

By day a very serious-minded surgeon in the East End of London (the world of Call the Midwife, where he also patched up victims of the notorious gangland Kray twins), he - like so many of his British male contemporaries - found in the world of Bond the perfect antidote to the grey strictures and privations of life in the profoundly economically depressed England after the war.

He was also a somewhat remote figure emotionally to his son, but one of the things we both loved and bonded over (forgive the pun) was Ian Fleming’s creation: the books and the films that followed (and I am guessing this is an experience shared by many sons and fathers of our generation).

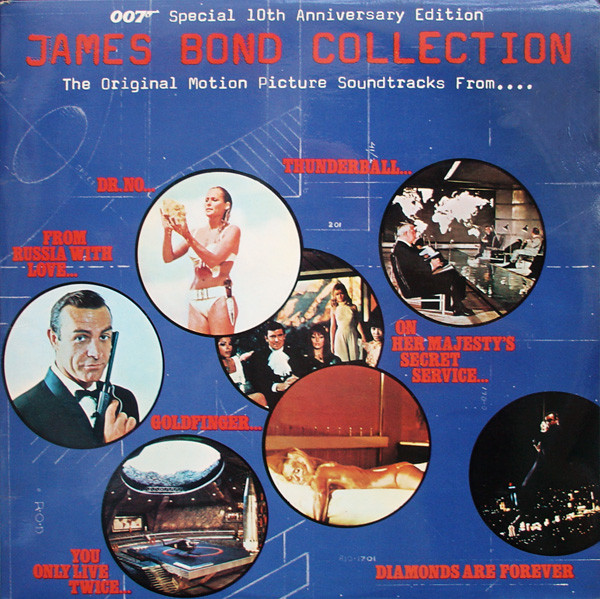

The films only brought the Bond world into sharper, more ebullient focus, and the moment he felt I was old enough he took me off to see You Only Live Twice at the Odeon Hammersmith (scene of David Bowie’s farewell to Ziggy Stardust, and numerous other classic rock shows; boy did I see some great shows there myself). I was sold, and we proceeded to catch every one of the older films in their regular revivals at second-run theaters and on TV at Christmas - a British ritual. I also became an instant, crazed John Barry fan (still am to this day), and picked up every soundtrack album and compilation I could lay my hands on. One of my favorite of these was a deluxe double LP set of highlights from all the film soundtracks up to and including Diamonds are Forever (1971), with extra photos all bound up in a “secret dossier”-style gatefold. (Seek out the UK pressing of this).

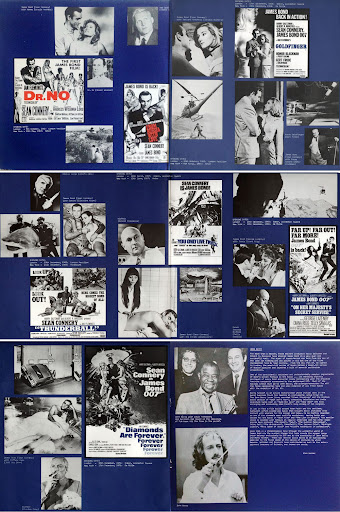

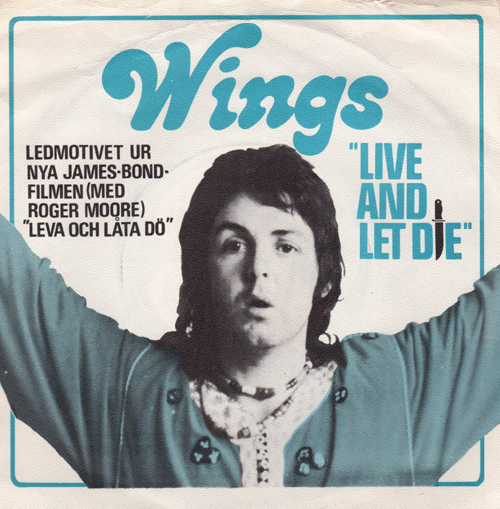

I’m telling you all this because, at the age of 13, the moment I heard Paul McCartney’s theme song for Live and Let Die - probably on the radio - I knew I had to have the soundtrack album (I was never much of a singles kid - always went for the full albums). This was even before seeing the film. Knowing I lacked enough pocket money savings to cover what was not a cheap record, I figured my best tactic was to get my father on board with the purchase. I dragged him to a little local music store and we promptly took up occupancy in one of those listening booths that were an intrinsic part of every record store in those days.

Record Listening Booths in the 1960s

Record Listening Booths in the 1960s

Down dropped the needle, and by the time the song launched into the first of its hyper-active bridges composed by George Martin to link the different verses and provide suitably Bondian action-music to follow on from the massive orchestral chords that greeted McCartney’s quoting of the film’s title - “Live and Let DIEEEEEEE!!” - I knew my father couldn’t resist. We went home with a copy clasped in my hot little hands ready to audition at full volume on my recently acquired stereo.

This is without doubt one of the supreme Bond title songs, all the more remarkable for rising to the challenge of matching (and in some ways even exceeding) the classic theme songs for Goldfinger, From Russia with Love, Thunderball, You Only Live Twice, Diamonds are Forever, and, one of my personal favorites, the all-instrumental, Moog-driven theme to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

That McCartney’s Live and Let Die is an unequivocal success is demonstrated by the excellent cover versions out there, not least of which is the wailing, metal barnstormer by Gun ’n Roses. I myself am more partial to Chrissie Hynde’s rendering on David Arnold’s essential album of Bond covers, Shaken and Stirred, which desperately needs a vinyl release. (Chrissie Hynde had earlier penned and performed the greatest Bond song nobody knows, Where Has Everybody Gone, for Barry’s final outing - and one of his best - The Living Daylights (1987) - a score crying out for the LaLaLand deluxe treatment).

The story of how McCartney and his wife Linda came to write one of the definitive Bond songs (and, I would argue, one of Paul’s very best post-Beatles numbers) is told in depth in Jon Burlingame’s book and the sleeve notes that accompany this release.

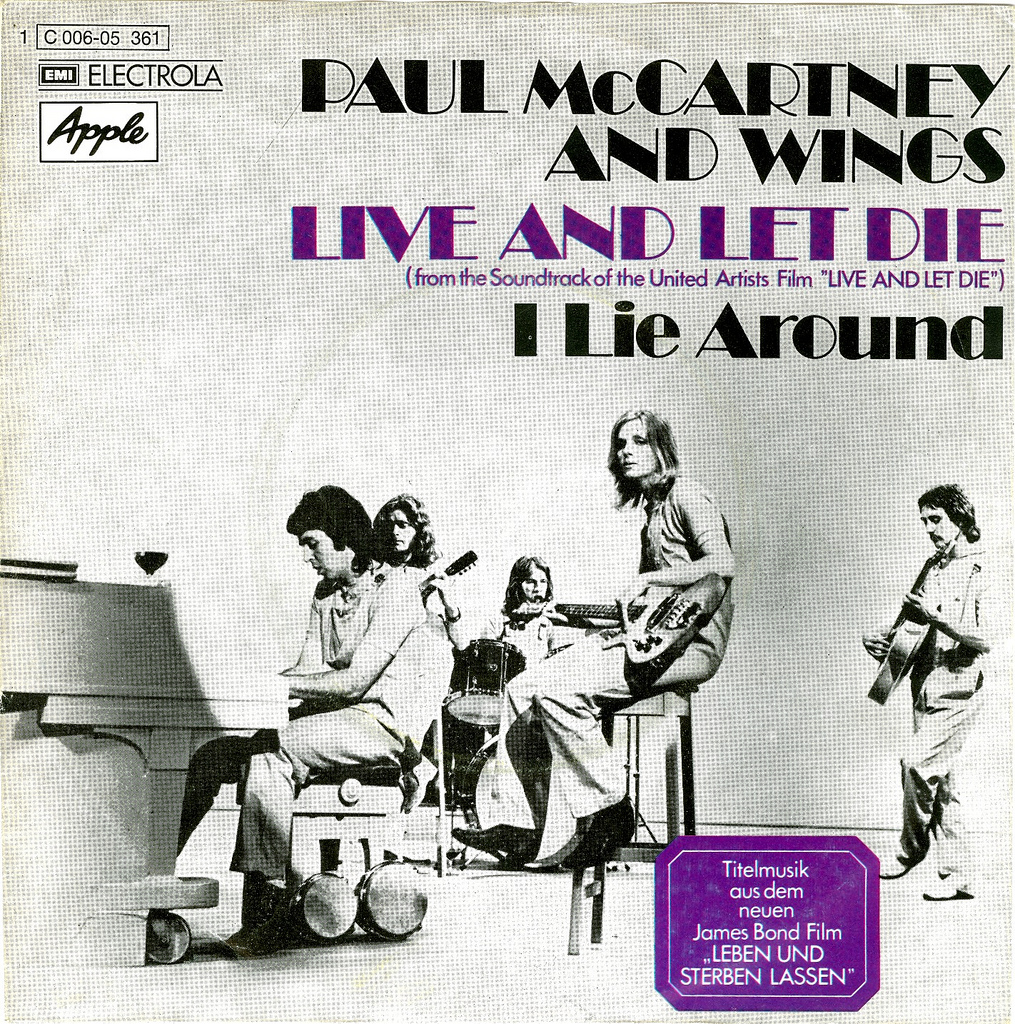

Barry, after a less than happy experience with Diamonds are Forever (including co-producer Harry Saltzman casting shade on his evocative theme song), was busy with other projects and not entirely in sync with the new lighter direction for Bond, which was already evident in Connery’s last outing. Ron Kass, a former executive at Apple, was now running Harry Saltzman’s non-Bond production company, and he contacted McCartney.

Burlingame takes up the story in his book:

“If you’re the kind of writer I am,” McCartney later said, “it’s always one of those little ambitions: do the Bond song”.

McCartney… got a copy of the Fleming novel and reportedly read it on a Saturday, probably in late September or early October 1972. “It’s a very fast read,” McCartney later told England’s "Mojo" magazine. “On the Sunday I sat down and thought, OK, the hardest thing to do here is to work in that title…. So I thought, ‘live and let die’, really what they mean is ‘live and let live’, and there’s the switch. So I came at it from the very obvious angle. I just thought, ‘when you were younger you used to say that, but now you say this.”

Linda McCartney contributed to the lyrics, and also came up with the midsection of the track, the reggae-inflected “what does it matter to you…”, a nod to the film’s Caribbean locations.

Crucially, McCartney contacted his old Beatles producer George Martin to help take the song to the next level, and it was the success of what they came up with that resulted in Martin writing the film score.

Burlingame continues:

“Paul contacted me to say he wanted to make a demo of a song he had in mind for a Bond film,” Martin later recalled. “I went to his house in St. John’s Wood and he played me his ideas on the piano, but when he described what he wanted it was obvious that a large orchestra would be necessary. In those days synthesizers and computer effects were in their infancy, and nothing would beat the sound of a large orchestra.”

At Martin’s AIR studios, “we started by using Paul’s band, and I used Paul, Linda and Eric Stewart to sing back-up vocals. I then went away and wrote the score for overlaying, using about 55 musicians. Some demo! That became the final version; I could not make it any better,” Martin said. He also double-tracked McCartney’s voice although, as Martin later said, “Paul does it so accurately that it almost sounds like a single voice, though it still gives a stronger and better sound.”

An interesting tidbit: percussionist Ray Cooper, best known for his long assocation with Elton John, provided some choice overdubbing during the sessions.

In one of the more mind-numbing revelations contained in Burlingame’s book but not repeated in the sleeve notes, once Harry Saltzman had heard the “demo” he summoned Martin to the set in Jamaica and declared:

“Very nice record… Like the score. Now tell me, who do you think we should get to sing it?”

Clearly as tone deaf on music issues here as he had been on Barry’s song for Diamonds are Forever, Saltzman had to be gently but firmly apprised by Martin and others of McCartney’s status and potential clout not only for the film’s box office but the single’s prospects in the charts

The success of the McCartney single resulted in Martin being offered the job to score the film, a job for which he was more than adequately equipped given his extensive classical training at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, and his previous film work.

In his book, Burlingame recounts how Martin... 'remembered calling his old EMI colleague John Barry “and kind of apologized for taking over. He was a good friend and had no problems. I heard about the row he had with Saltzman, and his advice to me was, "Just screw ‘em for me, would you?"'

John Barry (l.) and George Martin

John Barry (l.) and George Martin

Contrary to what the average listener might think, Burlingame reports, ‘the blaxploitation trend of the time, including the success of such soul-driven soundtracks as Shaft and Superfly, was not an influence. Martin said: “I just wanted to make as dynamic a sound as I could without losing the Bond feel. It was a long job, and I was given four weeks before I had to start recording. My speed of fitting and scoring for a large orchestra was about two minutes per day….” He conducted an orchestra of “around 55” at his own AIR studios in the late spring of 1973.’

Opinions have varied on Martin’s score over the years, but when I dusted off my trusty OG UK pressing a few years ago, I was newly impressed by how well Martin captures the unique atmosphere of the film, very different from previous Bonds. This film draws much of its energy from its juxtaposition of an urban black America of the early 70s with the exotic locations of Jamaica and New Orleans, overlaid with voodoo superstition and magic. Anyone seeing the film might be surprised to learn it’s one of Fleming’s stronger, grittier novels, but that edge survives mainly in the rockier feel of the soundtrack. This successfully blends McCartney’s song with a reinvention of the Barry “sound” in more modern, poppier and unusual instrumental colors. This is a Bond soundtrack living in a new era, an edgier sonic milieu than the Barry scores which had already begun to reflect their composer’s move towards a more Romantic, classical idiom than his earlier jazz-inflected music.

If only the film itself fully lived in that grittier, earthier milieu. Rather it tries to have it both ways by leavening the grit with the light sophistication of Moore’s portrayal and all the glamour and internationalism that increasingly defined the franchise. In many ways, viewed some 50 years after its release, the music is one of the more successful and least problematic elements of the film.

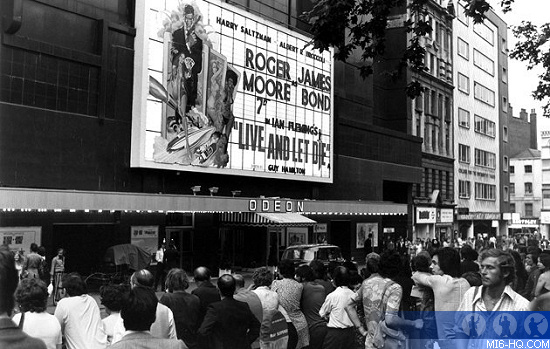

Premiere of Live and Let Die at the Odeon Leicester Square, London - Home to Bond Premieres for many Decades

Premiere of Live and Let Die at the Odeon Leicester Square, London - Home to Bond Premieres for many Decades

Of all the Bond movies, Live and Let Die has aged the least well. It’s a film you can’t suffer more lightly by taking it as a complete joke, like Moonraker. This is a film that fully plays into what today we see as troubling stereotypes of its time. The fact that they are presented both with a degree of seriousness for dramatic purposes, but also levity for commercial purposes (and to match Moore’s portrayal), only makes matters worse. The problems with Live and Let Die are hard to ignore - even for someone like me heavily disinclined to trash older films for not complying with current notions of what’s PC. From the black gangster Mr. Big (imbued with a presence and menace that defies the script and his surroundings by the incomparable Yaphet Kotto in an early starring role) imprisoning his virginal white goddess, Solitaire (played in her screen debut by Jane Seymour), who must be deflowered and rescued by the British knight in shining armour (!!!), to the admittedly hugely entertaining caricature of a white-trash sheriff who gives fruitless chase to Bond across the Louisiana bayou, this is a Bond film that can be uniquely uncomfortable to watch for even the most avid Bond fan.

Four German Posters from the Original Release

Four German Posters from the Original Release

Also problematic is the shift in tone of the series, as Roger Moore assumes the title role in a lighter vein that is perfectly matched to the increasing reliance on chases, stunts and gadgets. Director Guy Hamilton, who had also helmed Goldfinger and Diamonds are Forever, pushed strongly for taking Bond in this new, lighter direction. The narrative devolves into a more episodic structure built around endless attempts to unsuccessfully knock off our invincible hero. Moore is charming, engaging, and adept at the Bondian quip, but his insouciance isn’t enough to rescue the film from feeling so light it might float away.

Roger Moore

Roger Moore

One yearns constantly for the bite and menace Connery would have brought to this thing - not that he would have touched it with a 10ft. barge pole, even with an increase in the one million dollar payday he had received for Diamonds are Forever

The only thing working against all these negatives is Martin’s rockier score, which lends real atmosphere to the proceedings. It’s a good listen, full of imaginative touches. However, the music can nevertheless sometimes sound like it is devolving into vamping to match the episodic nature of the narrative. There is rarely a sense of the through-composed score. For all the rocky, funky gyrations of London’s top session musicians on fine form, the score rarely coalesces into the greatness of say, Goldfinger, From Russia with Love, Thunderball, You Only Live Twice (massively underrated in my opinion), and Barry’s Bond masterpiece, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

However, this is not to say there aren’t numerous pleasures to be had along the way, most of which are featured on the original soundtrack album (included on the second CD of this set). Martin fully exploits musically all the travelogue and dramatic prompts offered by the film.

He also successfully re-invigorates the familiar Barry tropes, like the Bond theme itself, with colorful instrumental additions, including extra percussion and rhythm guitar.

Recorded in Martin’s state-of-the-art AIR studios in the heart of London’s West End, the score is beautifully captured by staff AIR engineer, Bill Price, who would go on to record a number of key rock albums, including The Clash’s London Calling.

George Martin (l.) and Bill Price

George Martin (l.) and Bill Price

The advantage of this LaLaLand complete edition is that on CD 1 you get to hear every cue in the order in which it appears in the film, and by reading along with Burlingame’s excellent breakdown, you get a truer sense of the soundtrack as a whole. Highlights include the voodoo scenes, the funkier action cues (which make ample use of killer rhythm guitar), and the music for Solitaire. Note the prominent use of the harpsichord, an instrument Barry himself favored quite often.

Another delicious cue accompanies the scene where a poisonous snake slinks into Bond's shower and is only despatched by a creative use of the hero's M-modified after-shave. Martin has a blast with his use of slinky string figurations to capture the snake's movements and menace.

Ancillary pleasures include the immaculately executed funeral music that accompanies a funeral on the streets of New Orleans. This is the work of New Orleans jazz man Milton Batiste (same family as Jon Batiste), and his Olympia Brass Band does the honors here. The music shifts into more jubilant mood after the murder of a watching MI-6 agent.

The scorching “Filet of Soul” cover version of the theme song by B.J. Arnau, which accompanies Bond's excursion into a New Orleans club, almost steals the show. Arnau had made her name on the London stage in productions of Kenneth Tynan's controversial Oh Calcutta! (which featured extensive on-stage nudity and sexual content) and the rock musical of Two Gentlemen of Verona.

The song arrangement is purely Martin’s work (McCartney had no hand in it), and I defy anyone to suggest it could be bettered.

Some of the extra source music cues on CD 2 - such as Sacrifice - reveal Martin’s encyclopedic knowledge and ability to write in all genres of music, skills he put to great use not only on the Beatles records, but throughout his incredibly eclectic recording career.

As to sound, here there might be some differences of opinion from listener to listener. The score itself was remixed by Chris Malone (except for the New Orleans funeral music and the B.J. Arnau cover of the title song). Unlike the LaLaLand John Williams set of the Harry Potter scores I reviewed here, which breathed fresh life into the music, here the remixing and remastering - while revealing new details in the scoring - leans towards a tell-tale CD brightness which can become fatiguing over time. Popping on my original UK pressing of the original soundtrack album presented a far more organic and inviting sonic experience. It also underlined the fact that perhaps George Martin’s score is best experienced in foreshortened form, with various cues elided together, and thus less repetition of the same musical material. The original soundtrack album gets you all the best bits, including that incredible title song, its fierce soul cover version by B.J. Arnau, the authentic New Orleans funeral music and second line, plus all of George Martin’s best work in a very digestible 40 minutes or so.

Listening to the original LP, I experience the Live and Let Die soundtrack almost as a time capsule of cool Easy Listening circa 1973. For the diehard James Bond completists, the LaLaLand deluxe limited edition is a mandatory purchase and will yield many pleasures, not least those extra photos and comprehensive Jon Burlingame notes and commentary. Just be aware, when these limited editions are gone they’re gone, but don’t be put off if the website shows the CDs are currently sold out - LaLaLand represses regularly and gives advanced warning of when a limited edition is nearing the end of its run.

However, for the more casual fan and the listener for whom the best sound is a priority, pick up an original UK pressing. It’s a slice of early 70s easy listening heaven with a kick-ass Bond song, groovy vamping by London’s top session musicians, a snapshot of authentic New Orleans second line c. 1972, and plenty of ear candy to keep you interested in-between. It’s probably the best of the non-John Barry Bond scores before David Arnold came onboard.

George Martin demo-ing Home Hi-Fi, c. 1964

George Martin demo-ing Home Hi-Fi, c. 1964