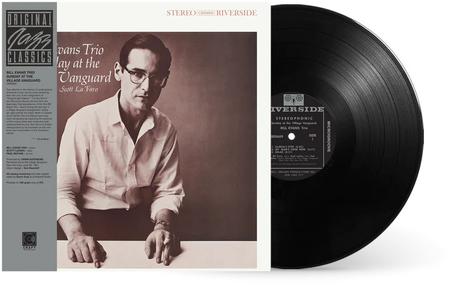

Bill Evans' Sunday at the Village Vanguard Gets a New Vinyl Shine

Another great-sounding (but not the best-sounding) Evans LP from Craft

This past summer, I raved in this space about Craft Recordings’ vinyl reissue of the Bill Evans trio’s 1961 classic Waltz for Debby, hailing it as the best-sounding of all the album’s many pressings. Now Craft has released an LP of the companion recording, Sunday at the Village Vanguard, as, once again, part of the label's Original Jazz Classics series. It too is a great album, and the Craft reissue is very much worth getting; but this time around, comparisons with previous pressings aren't quite so clear-cut.

Both albums were recorded live at the Village Vanguard on the same day, Sunday, June 25, 1961, over five sets—two in the afternoon, three in the evening. (This used to be the storied New York jazz club’s normal Sunday schedule, and there were three evening sets every day; now there are no matinees and just two evening sets.)

Eleven days after the session, the trio’s spectacularly innovative bassist, Scott LaFaro, who was just 25 years old, died in a car crash. Evans and Riverside Records’ proprietor, Orrin Keepnews, decided that, as a memorial, the album they released should include the takes with the best bass solos. They called it Sunday at the Village Vanguard. However, taking another listen to all the tapes, they realized that most of the best music was still in the cans. So, six months later, they issued Waltz for Debby. Jazz fans, critics, and historians properly consider the albums as two halves of the same concert, but most (also properly) treat Waltz as the better half.

(The notes from a three-CD boxed set, The Complete Village Vanguard Recordings 1961, released in 2005, reveal that Waltz consists of one track from the 1st afternoon set, two from the 2nd afternoon set, one from the 2nd evening set, and two from the 3rd evening set. Sunday consists of one from the 2nd afternoon set, three from the 1st evening set, and one each from the 2nd and 3rd evening sets. An additional 10 tracks, scattered throughout the five sets, weren’t released on either of the two albums.)

Both albums were revolutionary in their day—and remain enthralling more than 60 years later. The material wasn’t so adventurous: a mix of standards (Gershwin, Porter, Bernstein, Rodgers & Hart), originals (one by Evans, two by LaFaro), and two pieces by Miles Davis (whose band Evans had recently left). It was what they did with the tunes—the arrangements, spark, and edge—that was striking. This was a true trio—not a pianist backed by a bassist and drummer, but rather three distinct musicians carving an equilateral triangle, each asserting his prominence. Evans, who was classically trained, infused the melodies with Ravelian colors and chords. LaFaro adventurously veered between keeping time, plucking counterpoint, and laying down patterns that reinvented the concept of what a jazz bass can do. Paul Motian, coaxed off-center polyrhythms from the drumkit, swirling with sticks, slamming with brushes. Yet somehow their individual styles and crisscrossing paths bolstered and boldly underscored their group cohesiveness.

Both albums are among the best-sounding live jazz recordings. The bass and drums are particularly detailed and percussive; the ambience is alive (for better and for worse: audiences at the Vanguard, it seems, were way more talkative back in “the good old days” than they are today). I should note that the distinctions I’m about to draw are fairly subtle, even a bit audiophile-wonky. But this being an audiophile-wonky publication, the distinctions must be drawn.

I closely compared the Craft reissue of Sunday to the edition that I considered the best up to this point—Mobile Fidelity’s one-step plating mastered at 45rpm. The MoFi’s piano is warmer, though no less detailed or dynamic. I hear the lowest bass notes more clearly on the Craft, though the transient pluckings come through a bit more snappily on the MoFi. The MoFi also reveals a bit more air around the cymbals. Otherwise, the sound is much the same, and even the differences aren’t huge.

The bottom line is this: If you already own a MoFi pressing of Sunday—or, for that matter, the one in Analogue Productions’ QRP boxed-set of Evans’ Riverside albums, also in 45rpm—there is no reason to buy the Craft. At the same time, it’s worth noting that the MoFi is out of print, and the QRP is available only as part of a boxed set (i.e., it’s expensive). So, if you don’t have either of those earlier pressings, you can buy the Craft, knowing that you’re not missing a lot.

This isn’t true of Craft’s Waltz for Debby, which, I wrote at the time (and still believe), is worth buying even if you do have either of the earlier Analogue Productions pressings (the 45rpm or a 33-1/3 rpm HQ-180 edition mastered in 1992 by Doug Sax). I should add, even the best Sunday doesn’t sound quite as good as the Craft Waltz. It’s a mystery why this should be. It’s not as if the engineer, Dave Jones, changed the set-up from one album to the next; as noted above, the tracks from both albums come from the same live sessions. Kevin Gray, who re-mastered Waltz and Sunday for Craft, tells me that the tapes for both albums were stored together and seemed to be in roughly the same condition. Gray also told me that, for Sunday, about the only tweak he made was to boost the deep bass by “a couple of dB.” (This may explain the greater clarity of the lowest notes.)

The differences, then, may stem from the mastering. Krieg Wunderlich, who mastered the MoFi version, told me, when I reviewed it for Stereophile a few years ago, that he recalled “setting the machines up asymmetrically”—the left channel was different from the right—“in order to get the image to focus.” On both albums, the drums and bass are in the left channel, the piano in the right. The different ways that Gray and Wunderlich handled the left channel may explain the differences in the bass. Chad Kassem of Analogue Productions told me that he remembered Doug Sax spending many hours tweaking the Waltz tapes as well.

I don’t have access to the original tapes, nor was I present at their creation (I wasn’t quite seven years old at the time and lived more than 1,000 miles away from Greenwich Village), so the mysteries must remain unsolved in this space. Meanwhile, whichever vinyl slab of this music that you spin on your turntable, enjoy!