A Truly "Accessible" Don Cherry Record Reissued In the "Verve By Request" Series

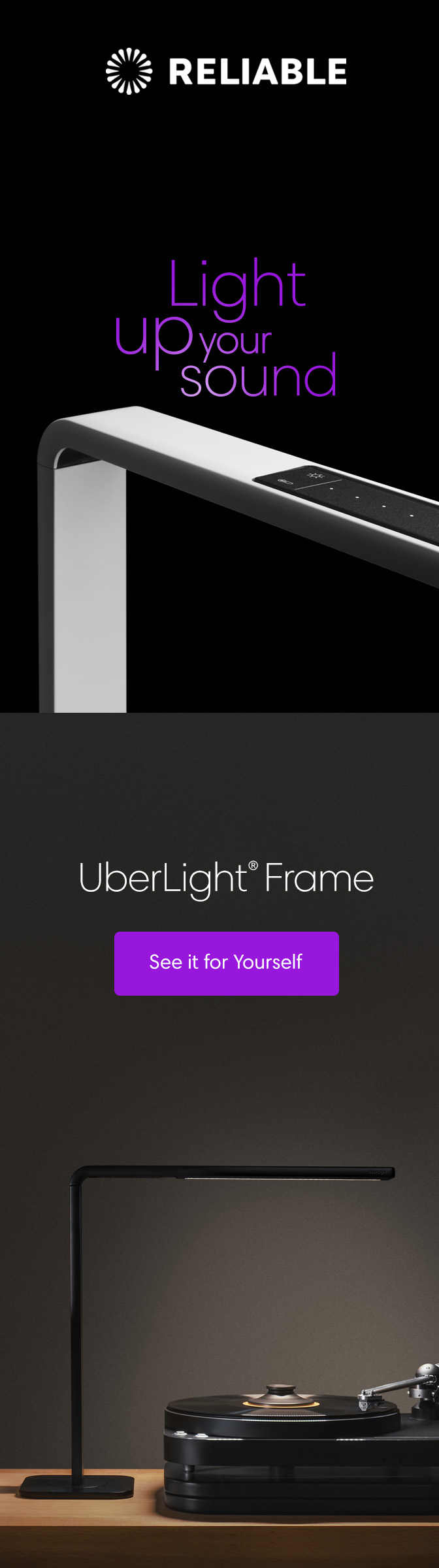

what's with those grooves?

In a recently published New York Times piece titled "The Worst Masterpiece: 'Rhapsody In Blue at 100" the pianist/composer Ethan Iverson pilloried the popular Gershwin piece as "naïve and corny"—and those were among the nicer things he wrote about it. The online comments are worth reading but one published letter is wroth quoting here: "By calling the work 'the best cheesecake,' Mr. Iverson aligns himself with a long line of critics who are quick to denigrate pleasure and valorize difficulty — truly a mode of thought that needs overhauling."

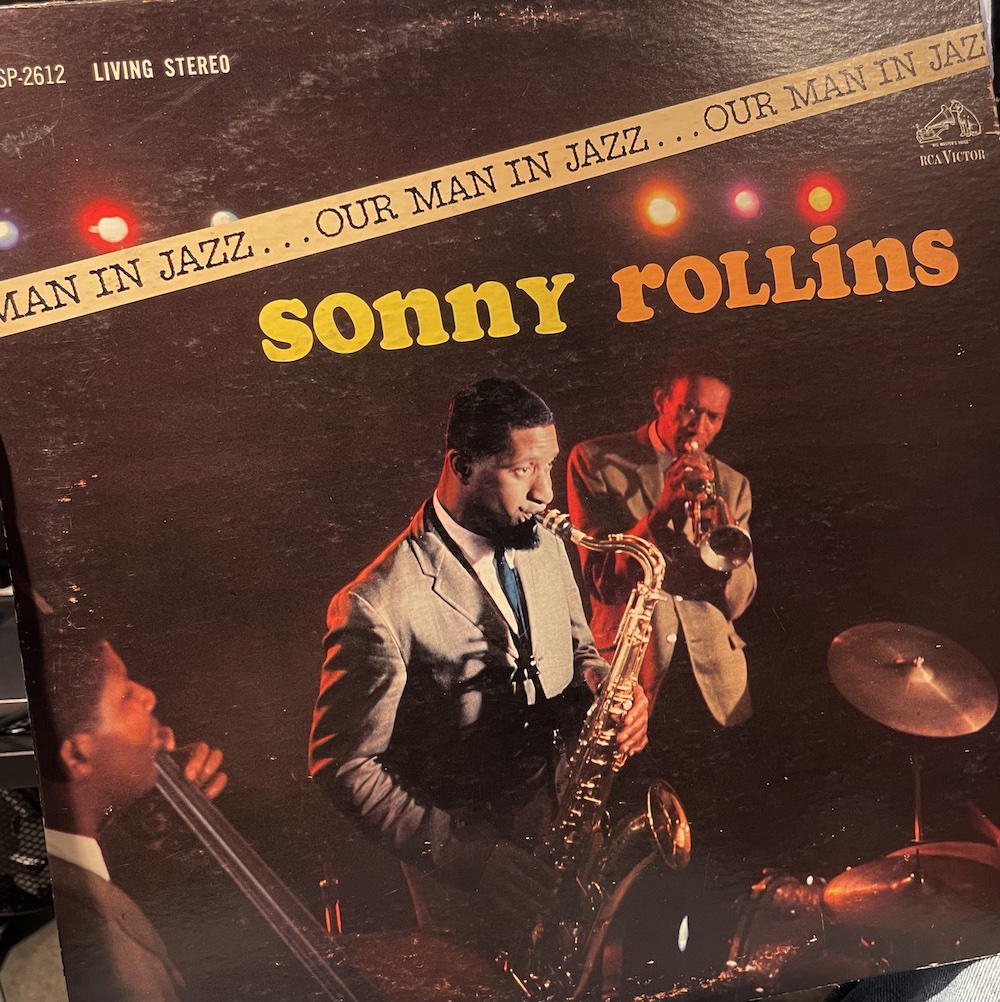

You could say some of Don Cherry's more difficult "free" jazz recordings "valorize difficulty", though they are worth sorting out in one's musical mind. At seventeen he was playing with Ornette Coleman and later after some difficulties including losing his cabaret card, which meant he couldn't work in New York, Sonny Rollins recruited Cherry to play on the sonically and musically spectacular live album Our Man In Jazz (RCA LSP-2612). The album kind of sounds as the cover looks.

This 1989 A&M release—part of the label's "Modern Masters Jazz Series"— features Cherry backed by a trio he'd worked with on some of the greatest jazz albums ever, including Ornette Coleman's Change of the Century and all of the others in the essential Atlantic Coleman catalog, plus one.

Cherry brought along to this session his high school friend James Clay a more "straight ahead" player for whom great things were in the cards, and who in mid '50s Los Angeles also played with Coleman. He was called back to Dallas, the liner notes explain, to deal with "family problems", which somewhat short-circuited his career, though in the long run, playing Coleman's "free jazz" style was never going to work for him. The liner notes include short pieces by Haden, Higgins and Clay (and a poem by Cherry). Clay writes, "Texas tenor players are known for playing in a raunchy, straight-forward manor, with lots of emotion and few frills". He also comments on his first trip to RVG's Englewood Cliffs studio and the sound the engineer produced here.

Clay's playing fits well in this quartet's "straight ahead" set that includes standards like "Body and Soul" and "Bemsha Swing" (at this point Monk's tune can be considered one) and from "My Fair Lady" "I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face." No surprise that the group covers Ornette's "Compute", "The Blessing" and "When Will the Blues Leave?" as well as a pair from Cherry and one each from Higgins and Haden.

This is not an "easy listening" set dumbed down for commercial purposes by a mainstream rock label aiming to enter the jazz record world! Herb Alpert was (is) too much of a jazz fan to try that move. Let's just say this is a much neglected, accessible musical gem deserving of a reissue.

It also deserved a much better sounding reissue than this curiously underwhelming mastering job by Kevin Reeves. This is a direct to two-track Sony 3402 (Dash) Van Gelder recording. The Dash format featured a stationary head and was featured 16 bit resolution at either 44.1K or 48K sampling rates recorded to 1/4" tape. The machines had a "Dolby-like" pre-emphasis/de-emphasis to deal with noise produced by early converters.

The sound of the original A&M release listened to today is in some ways sonically spectacular, with "crystal clear" cymbal hits, deep, powerful bass, and muscular dynamic range. First heard in 1989, the unfamiliar sound assault hit the ears in a most unpleasant way making it sound artificial and almost "synthesized" as opposed to the "organic" way recorded analog sound had conditioned listeners to expect. Yet nothing about it then sounded "bright", "harsh" or "grainy". In retrospect, this record played back on modern gear will delight and excite more than it will offend.

Bass is deep, tight and robust. The drum sound is powerful, with precise cymbal hits that ring true. Cherry's pocket trumpet sounds great as does Clay's saxophone. I'm sure RVG was thrilled with the results. You might be too, or you'll hear it as "synthesized fun".

I hadn't played this one in decades and enjoyed the sound far more now than my last recollection of it (there are no disc mastering credits to be found in the lead out grooves or even on Discogs so I'm not sure who cut it). In fact after the first play of the original I played it again!

The reissue is another story. Now did Kevin Reeves have a functioning Sony Dash machine to play back the tape? Or was the source a CD or a digital file transferred by who knows whom? I don't know.

What I do know is that when I pulled the record out of the sleeve it appears the grooves were cut with a fixed pitch! In other worlds a computer was not used to adjust groove spacing. The only way to get away with that, especially on a long, almost hour long set like this, is to cut at a really low level and that's how Reeves cut it. You have to turn it way up and when you get it to an acceptable level you hear a lot of groove rumble and noise (though the pressing itself is reasonably quiet—in other words had this been cut at a normal level, you'd say this was a good pressing.

Here's the original:

Here's the reissue:

Here's the reissue:

Trust me here: this is not a lighting trick. The sound of this reissue is unacceptably mediocre. It sounds just like the original! But played at low SPLs in the next room with the door closed.

Why does something like this get released? Damn shame. A needle drop would sound way better! Perhaps Reeves has an explanation. I'll try to find out.