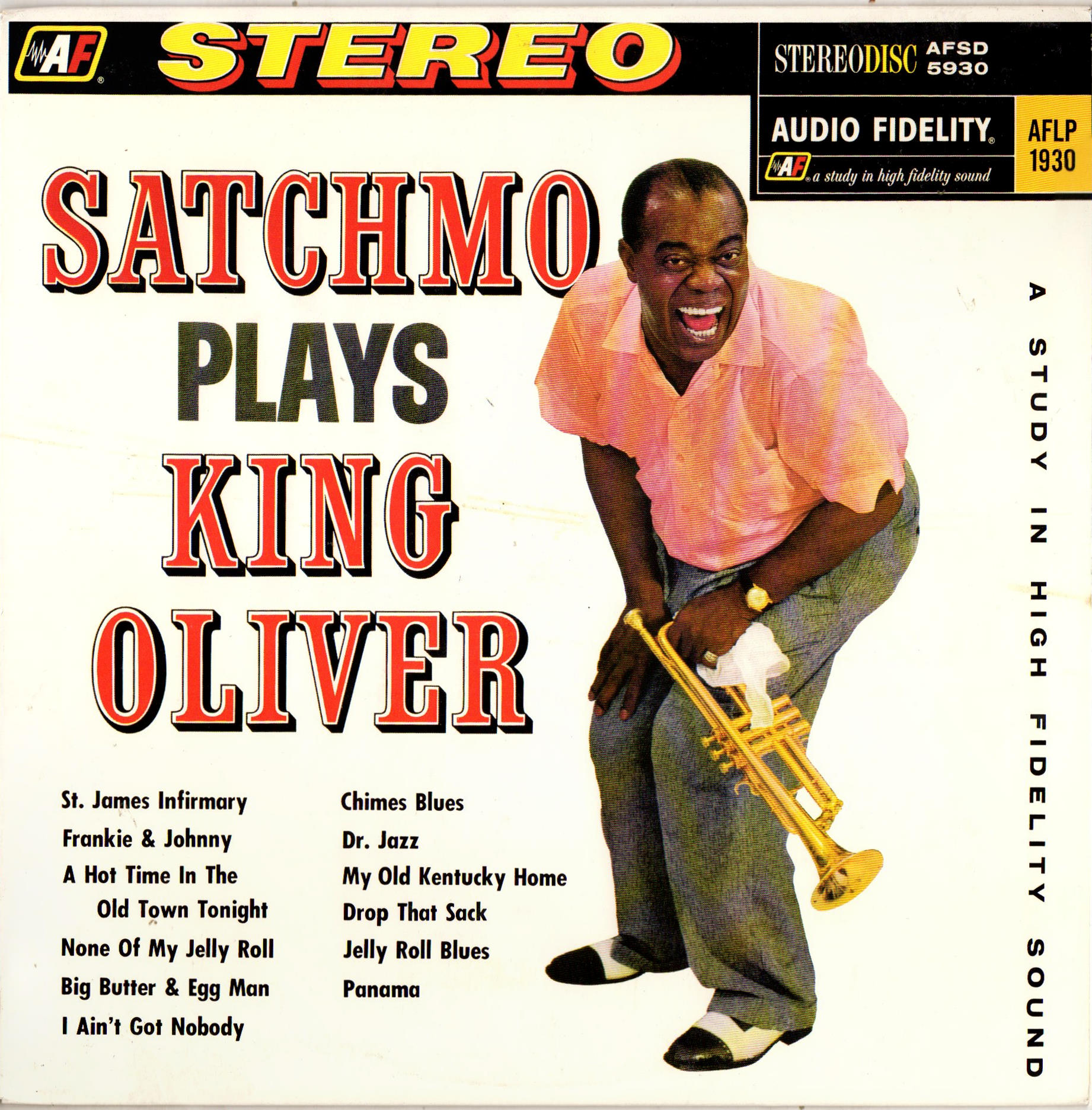

Satchmo Plays King Oliver---Louis Armstrong's Audiophile Classic LP

100th Anniversary Of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band April 5, 1923 Recordings---The First Black Jazz On Record

On April 5, 1923, one hundred years ago, in Richmond, Indiana, at the studio of Gennett Records, King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band made the first recordings by African American musicians that are indisputably jazz. They are also the first recordings of Louis Armstrong, who, during the next eleven years, would revolutionize jazz and popular music in America and the rest of the world. Mixing African vocal techniques and concepts of improvisation and rhythm with European notions of harmony, melody, and the virtuoso soloist, he would create the template for the music we've been listening to for the last century.

Joe "King" Oliver (1881?-1938) was a cornetist born in New Orleans who grew up in its unique musical culture. He was a great blues player and a master of the New Orleans polyphonic jazz style in which the horns collectively improvise over a strong, syncopated 2/4 rhythm. In 1922, King Oliver was living in Chicago, leading his Creole Jazz Band, and playing a long successful gig at the Lincoln Gardens, a dance hall in a Black neighborhood. Tragically, he suffered from a gum disease that would eventually end his music career, and it was beginning to affect his playing. Needing someone to bolster the sound of the band and lessen the load of playing four sets per night, he sent word to Armstrong, his former student in New Orleans, offering him the job of second cornet. Armstrong arrived in Chicago, two days before his twenty first birthday.

Oliver was an intelligent, innovative musician moving away from New Orleans traditional jazz by playing solos and lightening the rhythm to create a new forward momentum rocking groove. In the time-honored jazz tradition, Armstrong played second cornet, didn't upstage Oliver, listened, and learned while on the bandstand at the Lincoln Gardens.

In the spring of 1923, Oliver took the band on a tour of one nighters through the Midwest. In Richmond, Indiana, Gennett Records, a third-tier record company, owned by a piano manufacturer mainly recording local white dance bands, took the unprecedented step of recording a Black Jazz band. The company was also pressing records for the Ku Klux Klan, so we can assume that a commitment to racial equality was not its motivation.

Jazz records had already been made. The Original Dixieland Jazz Band, a quintet of white musicians from New Orleans, had recorded in 1917 and became a sensation, selling over a million copies of "Livery Stable Blues." They were certainly not "The Original" or even a particularly good "jazz band" by the standards of Black New Orleans. Still, their loud, brash playing, frenetic tempos, and pounding rhythms were unlike anything all but a very few white people had ever heard. Nick LaRocca, the cornetist for the group, claimed to be "the Columbus of jazz, the Sir Isaac Newton of the latest dance craze (!)." Many, if not most, of the people who bought the ODJB records believed him. The record companies, of course, jumped on the "jazz craze" and recorded many sound alike "five" groups, all composed of white musicians.

In 1920, Mamie Smith, a Black woman, recorded "Crazy Blues," which was a huge hit and proved that there was a large market for Black music made by Black people. Soon the record companies were recording dozens of Black female "vaudeville blues" singers, but recording a group of Black men playing jazz was a step too far until Gennett did it.

On April 5 and 6, 1923, King Oliver accompanied by Amstrong, second cornet, Johnny Dodds, clarinet, Honore Dutrey, trombone, Lil Hardin (soon to be Armstrong's second wife), piano, Bill Johnson banjo and Baby Dodds, percussion, recorded nine tracks. All except Lil Hardin and Bill Johnson were born in New Orleans. The recordings they made are the pinnacle of Black New Orleans traditional jazz and also the beginning of what would be called swing music. The band was starting to smooth out the chopping 2/4 rhythm and emphasize all four beats equally. Oliver made his "breaks" and solos a feature of the band and included pop tunes of the day in the repertoire but played them in Black New Orleans jazz style. Armstrong was to take all of these ideas and, with his genius, change music.

In 1959, Armstrong, then the most famous and popular Black jazz musician and a pop star, did something very unusual and recorded a tribute to Oliver. He was not a man to forget his roots or a friend and had paid tribute to Oliver before beginning his 1957 Satchmo: A Musical Autobiography four record set for Verve, with three tunes he had recorded with Oliver and introduced them by saying, "My man in those days was ol' Papa Joe—my friend, teacher and inspiration and a great creator." Armstrong had recorded tributes to W.C. Handy and Fats Waller, both of whom were considered major composers and still very well known in 1959, but Oliver, whose last recording was in 1931 and had been dead for more than twenty years, was much more obscure, and remembered only by traditional jazz fans.

Armstrong probably wanted to do an entire album tribute, but he was recording for Audio Fidelity, a label that focused on novelty, exotica, popular classical, and the bottom line. Other than a few albums by Lionel Hampton, Al Hirt, and Pat Moran, the only jazz group on the label was the Dukes of Dixieland, a white septet specializing in commercial, "straw hats and old time outfits" New Orleans "tourist" jazz that had made a long series of very popular and very corny albums. Armstrong's first album for Audio Fidelity paired him with them and consisted of some of his '20s and early '30s hits.

When it came time for Armstrong to record with his own band, it's hard to believe that the idea of recording an album of long forgotten King Oliver compositions was greeted with much enthusiasm by Sid Frey, owner of Audio Fidelity, and probably at his insistence, Plays King Oliver is a misnomer. Of the twelve songs, Oliver recorded only four, and only two were his compositions. The album is mainly updated versions, with Armstrong's current band of some more of his classics from the twenties and a few well known songs of similar vintage that he had never recorded.

The style of Armstrong's sextet, The All Stars, was a hybrid of New Orleans traditional jazz and swing. The front line of Armstrong's trumpet with clarinet and trombone- played a modernized, streamlined version of the New Orleans polyphony that the King Oliver band perfected but was backed by a swing era style piano, bass, and drums rhythm section that swung hard. Unlike traditional jazz, there was soloing by all the instruments, and the band did not play with a two beat feel but a solid, aggressive, at times, almost rock 'n roll 4/4. In New Orleans, jazz was played for dancing, and the All Stars were a great dance band. No matter the personnel, they always swung hard and joyously.

The 1959 "All Stars" was not one of the best versions of the band but was still very good. Trummy Young (1912-1984) was the trombonist and occasionally sang. He was one of the premier swing era trombonists and had played in the big bands of Earl Hines and Jimmy Lunceford and recorded with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. The clarinetist, Peanuts Hucko (1918-2003), was an excellent Benny Goodman style soloist. Pianist Billy Kyle (1914-1966) had been a member of the John Kirby Sextet, one of the most popular small groups of the swing era and influenced Bud Powell. In the All Stars, he was a hard swinging accompanist who would sprinkle his solos with bop phrases. Mort Herbert (1925-1983) played no frills, "hit the root and keep swinging" bass. Danny Barcelona (1929-2007) was the solid groove, always feeling the beat, even on ballads style drummer that Armstrong favored.

Armstrong was 58 in September 1959 when Plays King Oliver was recorded. His playing had become more economical, melodic, and less daring since the mid-30s when he had begun to aim his music at a mainstream audience, but his gorgeous, huge trumpet sound and incomparable swing were intact. He was still the greatest male jazz singer, if not the greatest of all jazz singers.

Plays King Oliver begins with "St James Infirmary," a folk song of much debated origin, which was recorded by both Armstrong (1928) and Oliver (1930). The tempo here is much slower than Armstrong's 1928 version and Young and Hucko play a three note ominous dirge figure before Armstrong enters to play the melody, making it swing even at the funereal tempo. Armstrong's vocal is a soulful masterpiece of jazz phrasing and storytelling. "I went down to St. James Infirmary…Saw my baby there. She was stretched out on a long white table, so cold so sweet so fair." He lingers over the word "fair," emphasizing how profoundly sad this story is. Then he makes the listener feel the anguish of loss, "Let her go, let her GO, GOD…….BLESSSSS her…….wherehhhhver she may beeee." The band takes it out stomping and tight with Armstrong playing the melody and some beautiful variations, ending with three ascending high notes, the last one held and vibrant, like a great opera singer. Clearly, his chops are in great shape, though less than three months before, he had suffered a heart attack while on tour in Europe.

"Big Butter And Egg Man," first recorded by Armstrong in 1926, is here performed in a modern, tricked up arrangement. Billy Kyle's introduction quotes Strayhorn's "Take The A Train." Then over an easy swing beat, Armstrong plays the melody while Young and Hucko play All Stars/New Orleans style. After solos by everyone, Armstrong scats and sings the melody while trading fours with the drums. Finally, on the out chorus, the fifty-eight year old Armstrong outdoes his twenty-five year old self, playing higher and with a bigger sound than he did on the 1926 recording.

"I Ain't Got Nobody," was first recorded by Armstrong in 1929 with a big band and featured one of his best '20s vocal performances and amazing trumpet. This version's vocal is a swinging, scatting masterpiece that plays masterfully with the beat, making his wildly creative phrasing seem totally natural. He tosses off the improvised line, "Won't some of you hot mamas, round here….sorttahhh….. jus' be mine?" and it's a moment of natural rhythmic genius. Billie Holiday said she learned how to sing by listening to him. Every other jazz singer did too. Armstrong's trumpet solo has his unique vocal, singing sound, staying close to the melody but subtly altering it and the rhythm.

"Panama" is a traditional jazz standard that dates back to 1912, though Armstrong didn't get around to recording it until 1950 with the first version of the All Stars. The band takes it a bit slower than the tune is usually performed and gets into a relaxed but rocking New Orleans groove. Armstrong's trumpet solo's first chorus has a semi-clam, but he digs in on the second and plays a tricky rhythmic figure that sounds more like Dizzy Gillespie than trad jazz. Everyone gets to solo, and they take it out with the other horns improvising around Armstrong's strong lead.

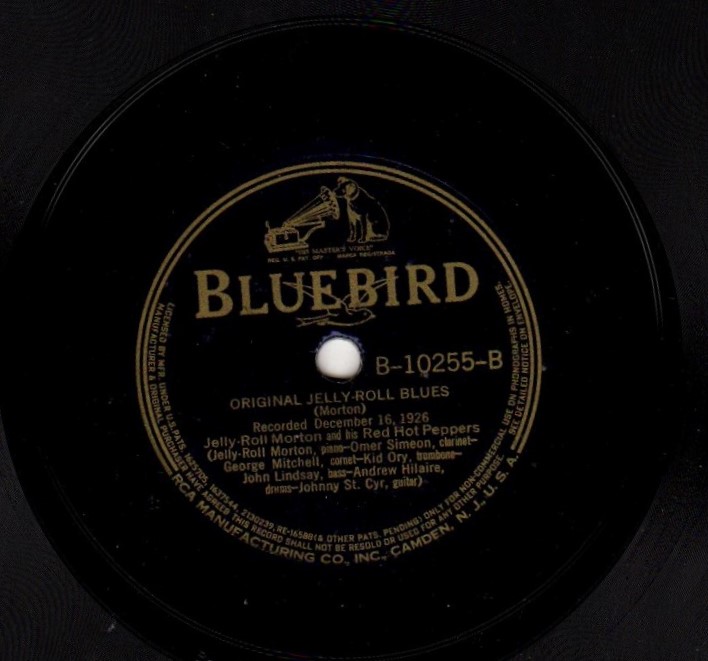

King Oliver composed "Doctor Jazz" and recorded it in 1927, but the track remained unissued until the LP era. Jelly Roll Morton beat him to the recording studio in 1926, and his blistering version is one of the greatest and most joyous jazz recordings. Armstrong had never recorded the tune before and elected to perform it at a mid-tempo 4/4 bounce which seems rather stodgy after you've heard Jelly Roll and his Red Hot Peppers' headlong, glorious, stomping 2/4. Sadly, he also decided to do the song as an instrumental, and we were denied the opportunity to hear Armstrong sing the lyrics that could have been written about him: "Oh, hello Central, give me Doctor Jazz! He's got what I need I say he has. When the world goes wrong and I got those blues He's the man that makes me get out of both my dancing shoes."

"Hot Time In The Old Town Tonight," a song that dates back to 1896, is not particularly suited to jazz treatment. Jazz versions are scarce, the most notable being Bessie Smith's in 1927. Armstrong had never recorded the tune before, and I suspect its presence on Plays King Oliver was at the request of Sid Frey, who wanted some Dukes of Dixieland type material. They recorded the song for Audio Fidelity in 1956. The arrangement with three drum solos is hokey, and Trummy Young's solo borders on mockery. Armstrong, though, never played less than his best, and his trumpet, especially in the last two choruses, is hot and swinging.

Another ancient song, "Frankie and Johnny" which tells the tale of a 19th Century love triangle killing was recorded by Oliver in 1929 as an instrumental, but Armstrong had never recorded the tune. "Honky tonk piano" albums of old barroom songs were a fad during the late fifties and early sixties. Though the liner notes claim that it was Armstrong's idea to record the song, accompanied only by an out of tune tack piano, I would hope that Sid Frey was to blame for such a failure of taste. Armstrong's vocal, for him, seems rather dispassionate and lacks his typical improvisatory flourishes. It was also a mistake to use the insipid Guy Lombardo lyrics that transport the cheating lovers from a barroom to "sipping soda" in a drugstore.

Armstrong had recorded "I Aint Gonna Give Nobody None Of This Jelly Roll" once before, and that was only two months earlier with the Dukes of Dixieland for Audio Fidelity's The Definitive Album By Louis Armstrong. This version is a little faster, and the All Stars are swinging in 4/4, unlike the Dukes' two beat. Armstrong's vocal is the highlight of the track. He sings two lines of the lyrics and then starts riffing with "I said Jelly, Jelly Roll," before going off on an amazing scat excursion for eight bars and improvising the rest of the lyrics. The swinging way he sings the off-the-cuff lines, "When you see me walking down the street, down where the cats all meet," is wonderful. In 1964, Audio Fidelity reissued Plays King Oliver under the title Aint Gonna Give Nobody None Of My Jelly Roll. Apparently, the ever vigilant guardians of public morality believed that Armstrong had a sweet tooth and was especially stingy with his pastries, and no complaints or consternation ensued.

"Drop That Sack" was recorded by Armstrong in 1926, in a group under the leadership of his wife Lil and featured some of his most aggressive playing of the '20s. This version is played much slower and lacks the raw energy of the original recording until Armstrong's solo, when he blows forcefully and plays a beautiful paraphrase of the melody. He plays a solo break, goes for a high note and misses it. Not to worry, on the out chorus, he hits it.

"Jelly Roll Blues" was written by Jelly Roll Morton about 1905 but not recorded by him until 1924. The song on the Plays King Oliver album called "Jelly Roll Blues" credited to Morton, is not the Morton song. Armstrong plays a basic slow blues in E flat, while Morton's classic 1926 band version of "Jelly Roll Blues" is in B flat, has an entirely different melody and a more complex chord pattern. Probably, Armstrong just told the band, "Play the blues in E flat" and the performance was improvised. The All Stars play a slow but swinging groove while Armstrong plays a solo with all the vocal inflections of the great blues singer that he was. Peanuts Hucko, who was not popular with many Armstrong fans who considered his playing "too modern," plays a relaxed solo with a warm New Orleans clarinet tone. On the last chorus, Armstrong soars over the band playing some thrilling high notes with his big vibrant sound.

"(My)Old Kentucky Home" is the Stephen Foster song composed nearly a hundred years before, and Sid Frey had to be responsible for its inclusion. He favored recording public domain, no royalty payments due songs and usually, somehow, he, a non-musician, managed to snag half of the arranging credit as he did here. The song is completely unsuited to jazz interpretation, and Armstrong had never recorded it before. Jazz versions were rare, but perhaps not surprisingly, the Dukes of Dixieland recorded it for Audio Fidelity in 1957 with co-composer credit to Frey. Armstrong sings his own lyrics except for the chorus, a good thing, and substantially alters the melody, also a good thing. His vocal is swinging, he even scats a bit, and there isn't the slightest hint of parody. The group sing along on the second chorus is a corny idea, but the three ultra hip jazz musicians make it through without snickering. On the out chorus, magic happens, and Armstrong plays a fantastic trumpet solo. Part of Armstrong's genius was that he could make great jazz out of the most unlikely material. He did it many, many times during his career. This is one instance.

"Chimes Blues," composed by Oliver, is the only song on Plays King Oliver that the King Oliver Creole Jazz Band recorded. It was the fifth tune recorded on April 5, 1923, and features the first recorded solo by Louis Armstrong. It was a two chorus blues solo, and his rhythmic assurance and swing were far beyond what anyone else was capable of in 1923. Clearly, he had rehearsed the solo at the Lincoln Gardens and was playing from memory, but for the last eight bars he played a clever variation on the theme that was seemingly improvised. Even the primitive recording method captured his full, brilliant cornet sound. At twenty-one, he sounded like Louis Armstrong.

Here, Armstrong plays the tune much slower with a shuffle feel. He probably couldn't remember the entire melody from thirty-six years before because he plays the catchy three note figure, but the rest is different. Trummy Young and Peanuts Hucko play melodic, two chorus solos that are maybe a bit too relaxed. Did they think this wasn't going to be the take? For Armstrong, every take was the take, and his solo is fiery and exciting as he seems to push against the slow tempo. In his first chorus, he hits a high F, but he's not done, and in the second plays a beautiful, soulful, even higher B flat before playing a descending figure to finish.

"Snake Rag" and "New Orleans Stomp," two songs recorded by the King Oliver Creole Jazz band in 1923, were recorded at the Plays King Oliver sessions but were not released on the Audio Fidelity album. They would have made welcome and appropriate additions to the album, replacing "Old Kentucky Home" and "Hot Time In The Old Town Tonight," but I suspect Armstrong vetoed them. The band had to be taught the tunes by Armstrong and seems tentative. He only remembered part of the tune of "New Orleans Stomp" and forgot the correct chord changes for one strain of "Snake Rag." Even so, their inclusion would have improved the album. "New Orleans Stomp" was a particularly unfortunate loss because Armstrong's on the spot arrangement is very pretty, and his vocal with improvised humorous lyrics extolling the beauties of New Orleans is outstanding.

Audio Fidelity was, in its heyday, an audiophile label that released in March 1958 the first stereo records available for purchase. The company's roster of artists was far inferior to the major labels, so eye catching covers, frequently of the cheesecake variety, and stereo sound were the selling points. Covers had "STEREO" emblazoned in large, bright letters at the top and promised "A study in High fidelity sound." The back covers usually had "Technical Data" listing the microphones used and diagramming their setup. Audio Fidelity was not above bragging. Several of the Dukes of Dixieland LPs, including the second one with Armstrong, proclaimed, "YOU HAVE TO HEAR IT TO BELIEVE IT!" Hyperbole was not necessary, for recording quality was generally very good, and sometimes outstanding, in the early stereo era live in the studio, natural style.

Satchmo Plays King Oliver was possibly the best Audio Fidelity recording and is one of the great early stereo LPs. Sid Frey may not have had great taste in music and songs, but he knew about good sound and how to record it. At a time when many of his competitors, including some labels that are iconic today, were recording in "ping-pong" or "hole in the middle" stereo, Frey knew better. "I like a broad panorama of sound so that each of the musicians is placed---and heard---according to where he'd actually be standing in performance. Also, we record with very little reverberation. There's already enough in the room. And we get all the presence, intimacy and warmth of the sound we can so the listener can identify himself with what's going on. Louis, for example leaves me emotionally exhausted; but it seems to me that until we recorded him, no one else had been able to capture his full impact."

That's a superb explanation of how to make an aesthetically and emotionally great recording, and Plays King Oliver is one. The musicians are spread out in front of the listener the way they would be on stage with the horns in front. Imaging is as good as it gets, "close your eyes and point at the bell of Armstrong's horn and watch him raise it to hit a high note" good. Low level detail is astonishing. You can hear that they are playing in a room and hear the overtones of the instruments in your room. Dynamic range is very wide and very close to live music quick. The drums sound tuneful, and the cymbals are sweet and musical without annoying high end sizzle. Bass is not ultra deep but melodic and you can hear the strings being plucked and then the decay. When Mort Herbert solos, you can hear his tapping foot and it is at the bottom of the soundstage. Most importantly, the recording of Armstrong's voice and trumpet is wonderful. When he sings, the low notes reverberate in his chest and the high notes in his head. The trumpet sound is thick, vibrant, and no other word for it, soulful. I have not heard another recording that captures the unique dynamic attack and pulsing sustain of Armstrong's trumpet sound that is so fundamental to its emotional impact. Plays King Oliver is one of the most lifelike and natural recordings I have ever heard. It's an audiophile classic.

Original Audio Fidelity stereo issues of Plays King Oliver were pressed on high quality vinyl and play very well, better than most other LPs of similar vintage. Later pressings, when Audio Fidelity had descended to the depths of budget label status, vary from horrendous to acceptable.

In 1999, Classic Records reissued the album on 200 gram vinyl in a near facsimile sleeve with mastering by Bernie Grundman. The front cover is well done, but the colors are slightly washed out on the photo of Armstrong. The pressing and vinyl quality is superb. The sound is warm and smooth with a slightly more extended treble than the original. The midrange is noticeably accentuated with a more extended dynamic range that emphasizes Armstrong's voice and trumpet. The soundstage is a bit wider, and there is more room air.

I thought the Classics version's presentation of Armstrong was superior to the original, and he is the main if not only reason to buy the album. The Classics LP also played much better than a clean Audio Fidelity original.

In 2017, Analogue Productions reissued a Bernie Grundman mastering of Plays King Oliver. I have not heard it. Possibly, it was pressed from the Classic Records plates.

The Analogue Productions LP is on The Absolute Sound Super Disc List, and the Classic version was included on our editor Michael Fremer's "157 In-Print LPs You Should Own!"

___________________________________

1. King Oliver's cornet playing became erratic as his gum disease progressed, and by the late '20s, he was not playing on many of his records. During the depression, he kept working with his band but frequently lost money on poorly attended shows. Band members usually made less than $4 per night and frequently nothing. In 1938, he was living in Savannah, Georgia, working in a pool hall. The owner said later, "He used to hang around the pool room. Then one day he asked if I could give him a job, something to help out. Well, there was no job, so I told him, go ahead and do what you can, sweep up now and then, and I'll give you what I can….Well, he closed up the grill one Saturday night. He was not in on Monday. Then someone told me, 'King Oliver died.' I gave his salary to the undertaker. It was a small amount." Oliver died of arteriosclerosis. He had stopped taking his blood pressure medication because of lack of money.

2. If you are able to help musicians in need: Jazz Foundation of America

3. A film was discovered in 2012 of Armstrong and the All Stars in the studio recording Plays King Oliver. The Louis Armstrong House Museum has posted on youtube "I Ain't Got Nobody," which is the album take and an outtake of "Aint Gonna Give Nobody None Of Me Jelly Roll.

Copyright 2023 and all rights reserved by Joseph W. Washek.