POMP and CIRCUMSTANCE: Music Fit for Kings and Queens PART 1: CORONATION MUSIC

A Survey of British Royal Music from Henry Purcell to Michael Tippett

Part 1: Coronation Music

With the Coronation of King Charles III nearly upon us, the British monarchy is preparing to "put on a show” the likes of which only those who were around for Elizabeth II’s Coronation in 1953 will have seen before. Royal weddings are all very well, but the Coronation ceremony is on a whole other level of pomp and circumstance, to borrow the title of Elgar’s five glorious marches celebrating King and Empire. And music will play a major role in the day’s proceedings, as it has for centuries.

So I thought this would be the perfect time to write a survey of records (and a few CDs) of music written for Royal ceremonies and special occasions through the centuries, many of which are of bona-fide audiophile quality.

No allowances need be made for the ceremonial origins of most of these works: all of these composers are working at the top of their considerable game. Diving into this repertoire is a great way to sample major British composers (and one German one) across the centuries, some of whose work you may not be familiar with. For those of you who are already familiar with the works of Purcell, Handel, Elgar, Walton, Britten, Tippett et al, this is an opportunity to discover some of their music (and recordings) you may not already know.

And there is no better place to start than with the ceremony that elevates a mere mortal to the role of King or Queen: the Coronation.

An English Coronation: 1902 - 1953

Down through the centuries the Coronation has blended religious text and doctrine with music of the highest order to create a unique moment of ceremonial pomp and theatrical spectacle on a massive scale. (The British Sovereign’s position as the titular Head - actually Supreme Governor - of the Church of England is why the ceremony is a religious one. For a longer discussion of the history and nature of the relationship between Church and State in Britain, I refer you to my footnote at the end of Part 2).

.webp) The Procession for Queen Elizabeth II's Coronation, 1953

The Procession for Queen Elizabeth II's Coronation, 1953

Just look at the footage from Queen Elizabeth’s 1953 Coronation with its massed crowds along the processional route to Westminster Abbey, and then the television broadcast of the ceremony itself (which lasted several hours) and you get some sense of what a powerful statement was being made about the primacy - at that time - of the Monarchy in British life; and how willingly the country’s citizens embraced that sense of order and the transition of power from one generation to another. It’s no understatement to observe that in the wake of the hardships and privations of the Second World War and its aftermath (which were felt disproportionately harshly in Britain), the Coronation of a young Queen communicated a new sense of hope and optimism.

Of course, 70 years on, the Monarchy finds itself in a very different position, as do most of Britain's institutions. Whether enough people care sufficiently in this day and age to line the route in their thousands for Charles as they did for his mother remains an open question. Unlike Elizabeth II, the new King ascends the throne with a lifetime of baggage, much of it insalubrious, and the country is a long way from even its post-Empire days of national pride.

Paul McCreesh recording An English Coronation

Paul McCreesh recording An English Coronation

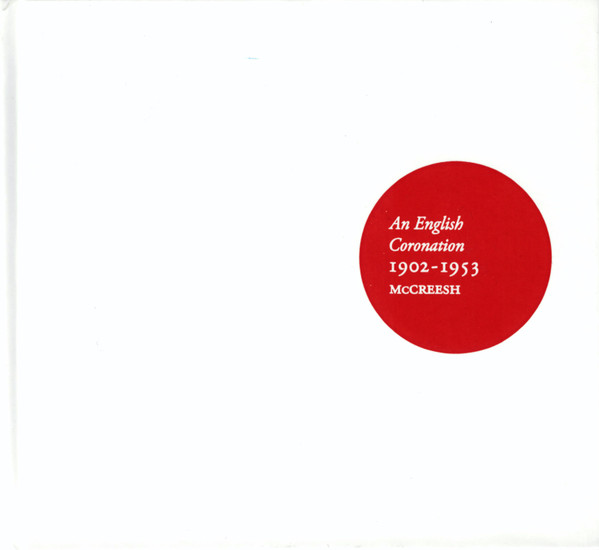

Still, the show must go on, and this recording project recreates and celebrates the Coronation ceremony of the 20th Century with the kind of imagination, scholarship and sheer verve that Paul McCreesh has brought to many similar undertakings. He burst onto the Early Music scene - and the record catalogue - in 1990 with A Venetian Coronation 1595 - Grand Ceremonial Music for the Coronation of Doge Marino Grimani. McCreesh and his fledgling ensemble of period instrument players and singers re-created a monumental ceremony - complete with interspersing plainchants - that took place in the Church of St. Mark’s, Venice with music composed by Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli. The Gabrielis - Uncle and nephew - were seminal figures in the development of Italian music during the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods.

Interior of St. Mark's, Venice (Rudolf von Alt, 1874)

Interior of St. Mark's, Venice (Rudolf von Alt, 1874)

The use of St. Mark’s cavernous interior to place antiphonal choirs of singers and instruments in different physical spaces, calling to and answering each other - so to speak - was a technique copied around Europe, and used in Westminster Abbey for numerous Coronations. Subsequent composers as varied as Verdi (in the Messa da Requiem), Benjamin Britten (in the War Requiem), and Karlheinz Stockhausen (in Gruppen) - continued to explore the possibilities of layering and moving music through physical space. (This recording - one of the first of its kind reproducing a specific historical occasion - was an early outing for the fledgling Virgin Classics label, and won the prestigious Gramophone award in the Early Music category).

McCreesh brings the same scholarship and performance élan to An English Coronation. He gathers together music from the four 20th century coronations: of Edward VII in 1902, George V in 1911, George VI in 1937, and Elizabeth II in 1953.

Coronation Procession of Edward VII in 1902

Coronation Procession of Edward VII in 1902

The music is presented within the context of the Order of Service from 1937, with the distinguished actor Simon Russell Beale (Penny Dreadful, My Week with Marilyn) reading the words that would have been spoken by the Archbishop of Canterbury. You can easily program the spoken sections out of your listening, but Beale’s performance is so on point, and the words are so evocative, that they lend not only context but also added impact to the music.

Where this recording gains is through the choice of recording venue - the splendid Ely Cathedral - and the recreation of the kind of forces that would have performed at the original services.

Recording An English Coronation in Ely Cathedral

Recording An English Coronation in Ely Cathedral

At the core we have McCreesh’s own performing groups: the Gabrieli Consort (choir), the Gabrieli Players (orchestra), supplemented by Chetham’s Symphonic Brass Ensemble.

Chetham's Symphonic Brass Ensemble

Chetham's Symphonic Brass Ensemble

Last, but far from least, is McCreesh’s secret weapon - the Gabrieli Roar. This consists of young choristers drawn from some dozen schools throughout England who partner with members of the Gabrieli Consort to receive vocal training and performance opportunities in a range of music. Their youthful enthusiasm shines through in every bar of their contributions.

The Gabrieli Roar and Consort

The Gabrieli Roar and Consort

As Paul McCreesh recounts in his exemplary and fascinating booklet notes, all four Coronation services were presented on a massive scale. There were some 400 singers (including 200 choirboys drawn from across the country), with three sub-conductors, several orchestras supplemented by massed military trumpets and, of course, organ. The Gabrieli team may not quite match the full choral forces of the original services, but they come pretty close. As you can imagine, recording such an array of musicians is quite the challenge for the technical team, especially working in a vast resonant space like Ely Cathedral.

Producer Nicholas Parker and Engineer Neil Hutchinson acquit themselves with distinction, though my one regret is that this was not issued on dual-layer CD/SACD. I can just imagine the extra definition and impact DSD would have imparted to the final product.

The selection of music runs the range of old familiars like Handel’s Zadok the Priest (performed at every Coronation since it was first presented to George II in 1727) and Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 (with its instantly recognizable “big tune” that, with words added, became Land of Hope and Glory). Lesser known gems harken back centuries to Purcell, Byrd and Gibbons.

The inclusion of Elgar's Coronation March during the music that precedes the service is especially welcome. Composed in 1911 it is - as McCreesh notes - more like a symphonic movement than a mere March. He quotes Elgar's biographer, Michael Kennedy: "... (it is) the greatest of Elgar's laureate works... a march written for the Abbey, not the streets of London, sombre and stately, and suggesting in some of its sections heroic tragedy. The orchestration is brilliant, but the undertones are often melancholy... as if the dead King was being remembered while the new one was crowned".

Coronation March by Edward Elgar

Parry’s iconic anthem, I Was Glad, sung as the King and Queen enter the Abbey, gains extra frisson here by virtue of the interpolations of the “Vivat” shouts (originally performed by scholars from nearby Westminster School), and the processional and antiphonal effects shared between the main Gabrieli Consort Choir as it processes into the Abbey to be greeted by the Gabrieli Roar. (This was one of my favorite anthems to sing in my school Chapel choir, and on one occasion I did get to perform it with extra brass - as heard on this recording - and the experience was electrifying).

I Was Glad by Parry

The Ceremony ends with that most bombastic and celebratory setting of the Te Deum by William Walton, followed by his Crown Imperial March. Walton essentially inherited the mantle of Edward Elgar as the go-to composer for Royal pomp and spectacle. His setting of the Te Deum is all explosive bursts of choir, organ and orchestra - heavy on the brass - marvelously captured here, though surpassed in another recording I will be talking about later.

The end of the service also contains a surprise: a specially commissioned new setting of the National Anthem, with a Recessional Prelude that quotes music heard earlier in the service. The composer is David Matthews who, along with his brother Colin, has created a catalogue of new music of rare distinction. (I interviewed him and his brother some 40 years ago when he was working as an orchestrator for Carl Davis’s series of original scores for silent films: it was clear already both brothers had distinct compositional voices). This work takes its place as an outstanding addition to the Coronation repertoire.

Recessional and National Anthem by David Matthews

This 2-CD package in book format is class all the way. Along with McCreesh’s excellent notes, there are a series of reminiscences by choristers who performed at each of the Coronations, as well as members of Gabrieli Roar recalling the recording sessions; plus full texts, bios, and a plethora of historical and session photos. Those kids of the Gabrieli Roar are clearly having the time of their lives!

This is the closest you will come to actually being at any of these historic coronations, and since this set came out I have found myself unexpectedly moved by the experience of listening to these discs.

An English Coronation 1902 - 1953

Gabrieli Consort and Players, Gabrieli Roar, Simon Russell Beale

Conducted by Paul McCreesh

Recording Producer: Nicholas Parker

Balance Engineer: Neil Hutchinson

Editing: Nicholas Parker, Neil Hutchinson, Paul McCreesh

Recorded in Ely Cathedral; Royal Masonic School Chapel, Rickmansworth; Church of St. Silas the Martyr, Kentish Town in 2018

Signum Records SIGCD 569 (2-CD)

Music: 10 Sound: 8

Edward Elgar: Pomp and Circumstance Marches and William Walton: Crown Imperial etc.

This is the music which, whether you know who composed it or not, is most readily identified with the British monarchy, and lends its title to this article. It is actually a quote from Shakespeare’s Othello: “…. the neighing steed, and the shrill trump, the spirit-stirring drum, the ear-piercing fife, the royal banner, and all quality, pride, pomp, and circumstance of glorious war….”

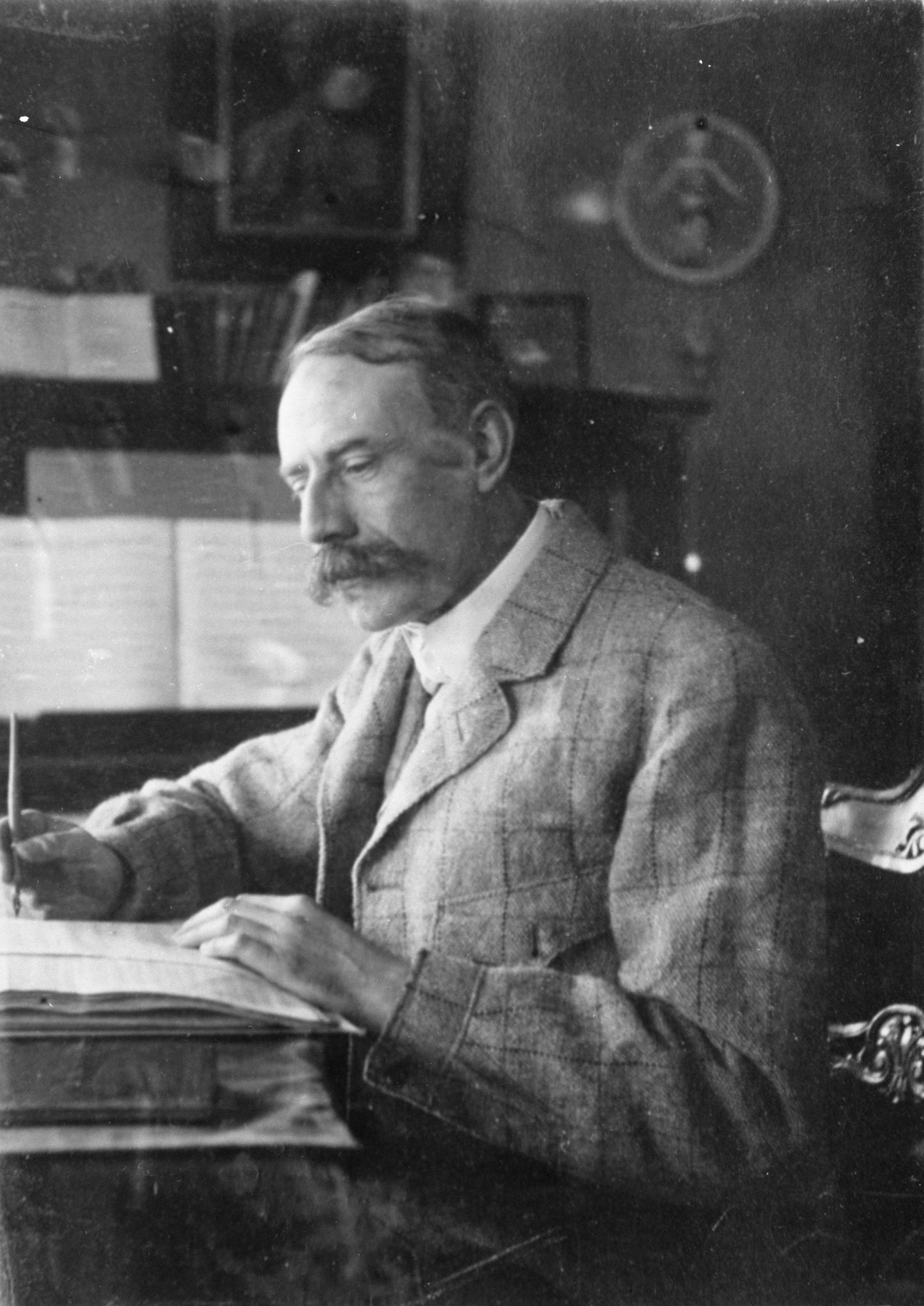

Edward Elgar

Edward Elgar

Long before he was officially appointed Master of the King’s Musicke in 1924, at the age of 68, Elgar had been recognized as England’s unofficial Music Laureate. His music then - and still to this day - embodied for many the ultimate sense of “Britishness”, of warmth and nobility, of benign rule over a vast Empire, at the head of which stood the monarch. At the time his music was written, this was how the majority of British citizens saw themselves, their King, and the place of their homeland in the world.

Of course this massively over-simplistic view had nothing to do with the reality of what Britain was actually all about during the heyday of its Empire and its international “influence”. Interestingly, if you listen beneath the surface of much of Elgar’s music (especially the First Symphony, whose first movement is built upon a slow theme ostensibly cast in the same mold as the trio sections of the Pomp and Circumstance marches) you will hear shadings that reveal a more nuanced and layered view of the Empire ideal. But what Elgar did buy into was the aspirational aspect of what King and Empire represented, at least for the British (if not all of their foreign subjects). And so this music, with its brilliant use of the march form, and its infinitely hummable melodies, became more or less instantly the de facto musical embodiment of Royalty and Britishness. The reason for its longevity lies in what Elgar’s biographer Michael Kennedy notes in his sleeve notes for the Boult recording: “Elgar’s complex genius enabled him to reflect this historical period in music which is certainly glittering and opulent also, but has a poetic vision reaching beyond the topical event. In all Elgar’s ceremonial music there comes a moment when we can hear a Kiplingesque warning: For frantic boast and foolish word - thy mercy on thy people, Lord.”

When it comes to memorable melodies, the first of these marches contains an absolute corker - and Elgar knew it. Early on in the work’s composition he wrote to his friend A.J Jaeger (“Nimrod” in the Enigma Variations) at his publisher, Novello’s: “Gosh! man I’ve got a tune in my head.” A few months later he told another friend: “I’ve got a tune that will knock ‘em - knock ‘em flat.” At the first London performance in October 1901 the audience was rapturous, demanding two repeat performances on the spot. When King Edward VII heard the work he advised Elgar to add words, which he subsequently did when it was integrated into the Coronation Ode, composed for Edward’s Coronation in 1902. As the King had prophesied, the tune went around the world. Today it is one of the essential barnstormers that brings down the house at every Last Night of the Proms at the Royal Albert Hall.

Sakari Oramo conducting Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 at the Last Night of the Proms

The other four marches in the set are no less memorable, each very different in character, though No.4 remains closer to No.1 in its essential character, and is my favorite. The melody in the trio section comes very close to unseating the similar tune in No.1. It is a huge testament to Elgar’s genius that the five marches can be performed and listened to as a sequence without outstaying their welcome.

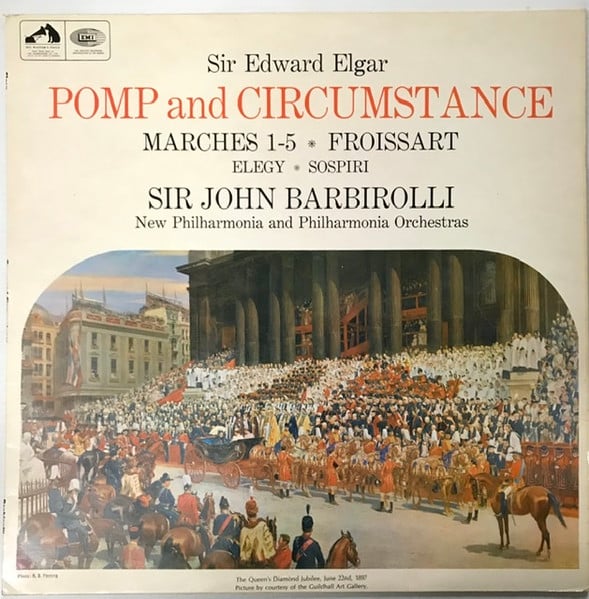

Needless to say there are many fine recordings of the marches, especially No.1, but I think it is safe to say there are three especially fine versions of all five marches which will make anyone happy. The first of these is on EMI and dates from 1966 and is by the great British conductor, John Barbirolli, with the Philharmonia Orchestra.

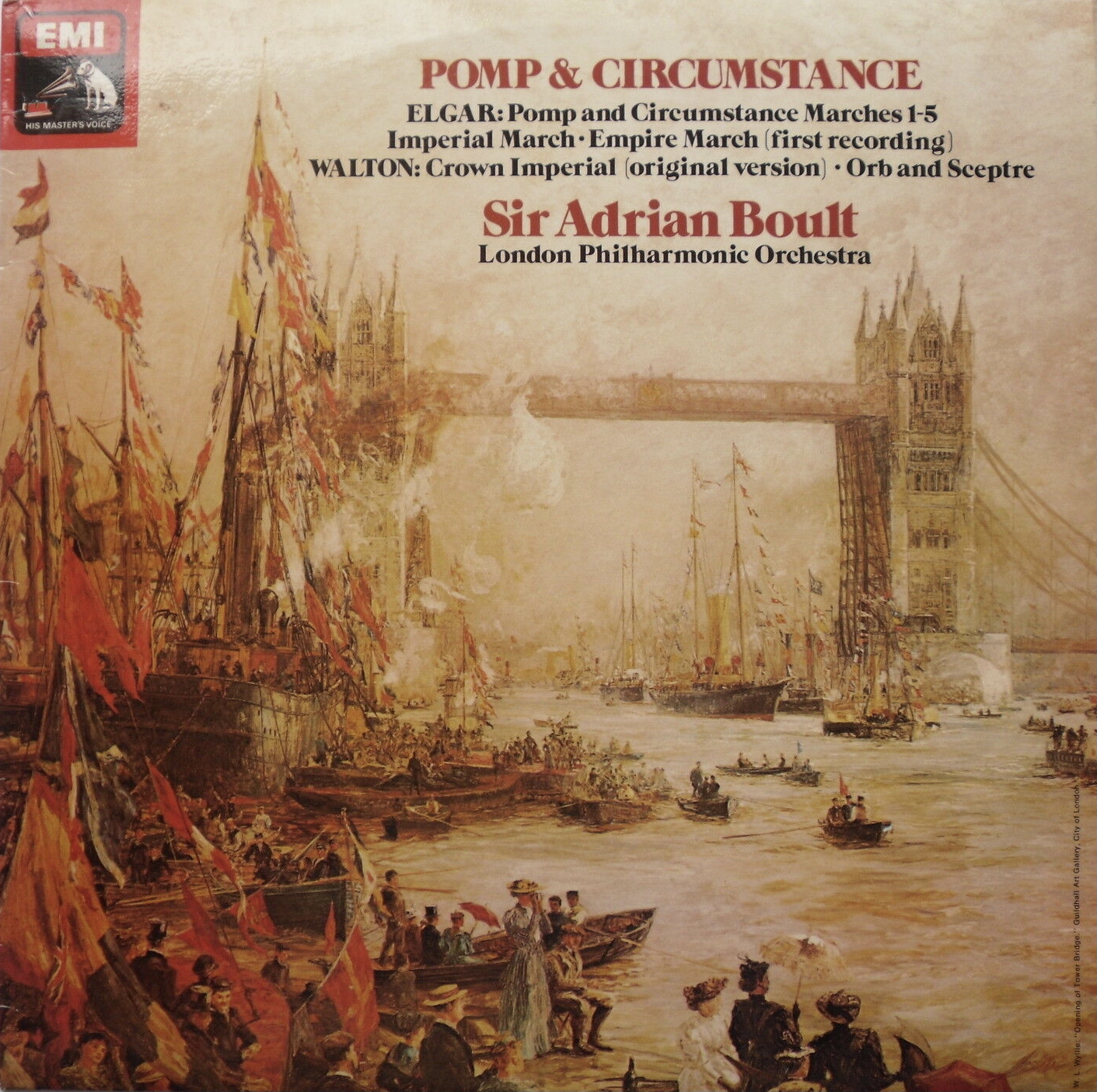

Then, in 1977 two versions were recorded with the same orchestra, the London Philharmonic: one with Georg Solti on Decca, the other on EMI by that other great British conductor of his generation, Adrian Boult. All three versions were recorded in Kingsway Hall - the scene for many audiophile classics - and all sound splendid in their various vinyl incarnations. Audiophiles with an ear for the details can directly compare Solti (engineered by the legendary Kenneth Wilkinson) with Boult (engineered by, as far as I am concerned, the equally great team of Christopher Bishop and Christopher Parker). Both sets must have been recorded within months of each other, so direct comparisons reveal much about the interpreters and the recording approach. EMI in general tended to favour a more mid-Hall perspective over Decca’s front row, conductor’s perspective, but here Wilkinson adheres more to EMI’s approach. As to performances, this was a time when Solti was immersing himself in Elgar, recording fine performances of the first two symphonies that really helped the works’ developing international reputation. In true Solti fashion it is a very tight, well-drilled account; Boult and Barbirolli are a little more laid-back.

Cards on the table: the London Philharmonic remains my favorite of the five main London orchestras (yes, five!!), and their rich sound is perfect for Elgar. Forced to choose, for me it’s Boult all the way, and the conductor’s series of 70s Elgar recordings were adorned with beautiful cover art reproducing quintessential paintings of London in its Empire heyday by William Logsdail (1859 - 1944), plus excellent sleeve notes by Michael Kennedy.

In the early-to-mid 70s, I heard Boult conduct the Elgar ‘Cello concerto with Paul Tortelier and the LPO in one of the state rooms at Windsor Castle. (Their 1973 recording is a fine alternative to the Jacqueline du Pré classic, and also includes a superb account of Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro and the Serenade for Strings). Boult, with his magnificent handlebar mustache, every inch the Edwardian gentleman, conducted almost without moving his body, all his considerable energy and will focused into the precise movements of the longest baton I have ever seen. The performance was riveting, glowing in suitably Autumnal colors. In his youth, while studying in Leipzig, Boult was strongly influenced by the great Arthur Nikisch, who in 1913 had made one of the earliest recordings of a complete symphony, Beethoven’s 5th, with the Berlin Philharmonic. Nikisch employed an intricate baton technique that Boult emulated.

In his recording of the five Pomp and Circumstance marches, Boult’s couplings are some rarer Elgar marches and Walton’s two superb contributions to the genre, Crown Imperial (1937) and Orb and Sceptre (1953).

Solti pairs his with the colorful Cockaigne Overture - a musical portrait of London - and Elgar’s fine arrangement of the National Anthem. Barbirolli gives you the Elegy, the lesser-known gem Sospiri, and the Froissart Overture.

Hell, just buy them all!

Elgar: Pomp and Circumstance Marches; Elegy; Sospiri; Overture "Froissart"

New Philharmonia and Philharmonia Orchestras conducted by John Barbirolli

Recording Producers: Christopher Bishop, Victor Olof

Balance Engineers: Christopher Parker, Harold Davidson

Recorded in Kingsway Hall in 1962 and 1966

HMV/EMI LP ASD 2292 (1966)

Music: 10 Sound: 9

Elgar: Pomp and Circumstance Marches; Overture "Cockaigne" (In London Town); The National Anthem

London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Georg Solti

Recording Engineer: Kenneth Wilkinson

Recorded in Kingsway Hall 1976 and 1977

Decca LP SXL 6848

Music: 10 Sound: 9

Elgar: Pomp and Circumstance Marches; Imperial March; Empire March

Walton: Crown Imperial (Original Version); Orb and Sceptre

London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Adrian Boult

Recording Producer: Christopher Bishop

Recording Engineer: Christopher Parker

Recorded in Kingsway Hall, 1977

EMI LP ASD 3388

Music: 10 Sound: 9

Elgar: Coronation Ode

Staying with Elgar we come to the earliest recordings of his Coronation Ode, commissioned by the Grand Opera Syndicate - the management of Covent Garden Opera House - for a gala concert that was supposed to take place on the day before the coronation of Edward VII in 1902 (owing to the King's poor health, the date was pushed back a few months). This was a secular work with texts fashioned by A.C. Benson, the son of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and at the time of the coronation a housemaster at Eton College - across the river from Windsor Castle, a school with long historic ties to royalty. Benson had already fashioned the words for “Land of Hope and Glory” (whose tune was derived from the first Pomp and Circumstance March, as recounted above). Elgar decided to integrate this into the Ode, so it made sense to ask Benson to fashion the rest of the libretto.

The text is no bland series of encomiums to the King and Country; it is full of prescient warnings of the vulnerability of the country in the modern world. It warns of what might follow should England become involved in a new war:

Under the drifting smoke, and the scream of the flying shell

When the hillside hisses with death…..

…. and never a foe in sight

This is a remarkable premonition of the nature of the military conflict in the First World War which broke out twelve years later.

In another section, a paean to the Arts, Benson celebrates the power of music:

Fiery secrets, winged by art,

Light the lonely listening soul….

Written at the end of the bloody Boer War in South Africa, itself a harbinger of the horrors of WWI, the Ode, while extolling King and Empire, is remarkable in its sense of the fragility of the moment. It yearns for a peaceful future, acknowledging the fact the Britain is enjoying a rare moment of security:

As the golden days increase

Crown your victories with Peace!

…..Tho’ thy way be darkened, still in splendour drest

As the star that trembles o’er the liquid West.

But ultimately the work ends with the assurance of Elgar’s magnificent Pomp and Circumstance tune to the words:

Hearts in hope uplifted, loyal lips that sing;

Strong in faith and freedom, we have crowned our King!

Elgar was clearly inspired by his text, and wrote the music on the grandest scale. The Ode was composed for four soloists, mixed chorus (Elgar wanted 44 sopranos, 34 contraltos, 42 tenors, and 40 basses), organ, a very large orchestra, with optional parts for an additional 36-piece military band.

There are two fine recording of the work that came out on LP. The first, its premiere recording, came out on RCA in 1977, and was one of the earliest done by Chandos, which subsequently became one of the most prominent and successful independent classical labels. It is coupled with another exceptional and rare Elgar work also receiving its premiere recording, The Spirit of England, composed during WWI between 1915 and 1917. Here Elgar plunges into the darkness of the times to find much needed hope and solace. A fine group of soloists and the Scottish National Orchestra and Chorus are conducted by the ever inspiring Alexander Gibson. My first UK pressing boasts quiet surfaces and excellent sonics (not always a given in RCA pressings of this vintage), and would be a first choice for the Coronation Ode were it not for the existence of a stunning audiophile classic that came out in the same year.

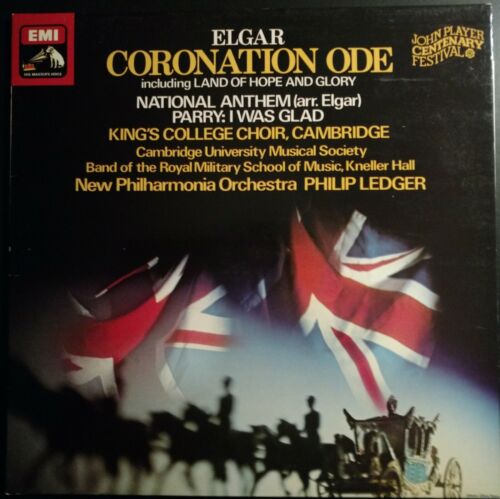

This record, which partners the Ode with Parry’s evergreen Coronation anthem I was Glad and Elgar’s stirring arrangement of the National Anthem, is one of the supreme gems in the 70s EMI catalogue, courtesy of its crack technical team of Producer Christopher Bishop and Balance Engineer Christopher Parker.

The arrayed forces captured on this recording are formidable: The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge (with boy trebles and altos), the Cambridge University Musical Society (with girl sopranos and altos), the New Philharmonia Orchestra, plus the Band of the Royal Military School of Music, Kneller Hall, all conducted by the then Organist and Music Director of King’s, Philip Ledger.

What makes the technical achievement of this record all the more remarkable is the fact that it was recorded in the cavernous acoustic of King’s College Chapel, a space that has proved to be challenging and treacherous to even the most seasoned engineers.

Just compare this version of Parry’s anthem to the one on the Paul McCreesh recording I discussed earlier. Whereas McCreesh’s version, for all its fine qualities, somewhat disappears into the resonant acoustic of Ely Cathedral, the EMI version somehow manages to articulate all the necessary detail (including the stunning brass fanfares and rumbling organ) while also keeping that vast echo present. It’s a remarkable feat. (Forgive this rough digital transfer - the LP sounds infinitely better).

Parry: I Was Glad with King's College Choir, University Singers etc.

As to the differences in the versions by Gibson and Ledger of the Ode, the former comes across as a more conventional large-scale choral affair, albeit excellently done, while the Ledger version has this wonderful layering between the more intimate Chapel choir and the larger Chorus, all infused with the energy of youth. In addition you have the thrilling overlay of the Military trumpets (considered one of the finest such ensembles in England). When the trumpets sound, the drums thump, and the organ interjects with its wall of massive chords, all while the choirs and soloists give their all, well it’s simply thrilling and raises the hairs on my neck every time. Just listen to the opening movement and you will get the general idea.

Elgar: Coronation Ode 1. "Crown the King!"

And when “Land of Hope and Glory” kicks in at the end, I defy anyone to carp at this overt declaration of patriotic pride.

I own the Alto AAA reissue and, if you love this music, it is definitely worth the extra money you will have to pay to acquire a copy. I must confess never to have heard a regular OG pressing (as with all EMI releases, go for UK pressings, NEVER American ones). For the few years it was operating, Alto produced some of the best sounding records in my collection. and it also focused on unusual repertoire. (Their reissue of Shostakovich’s 13th Symphony on EMI with Andre Previn and the LSO is another essential acquisition for any serious classical collector).

Elgar: Coronation Ode; the National Anthem; Parry: I Was Glad

Felicity Lott, Alfreda Hodgson, Richard Morton, Stephen Roberts

Cambridge University Musical Society, Choir of King's College Cambridge, New Philharmonia Orchestra, Band of the Royal Military School of Music, Kneller Hall

Conducted by Philip Ledger

Recording Producer: Christopher Bishop

Recording Engineer: Christopher Parker

Recorded in the Chapel of King's College, Cambridge

EMI (Alto Reissue) LP ASD 2245 (1977)

Music: 10 Sound: 10

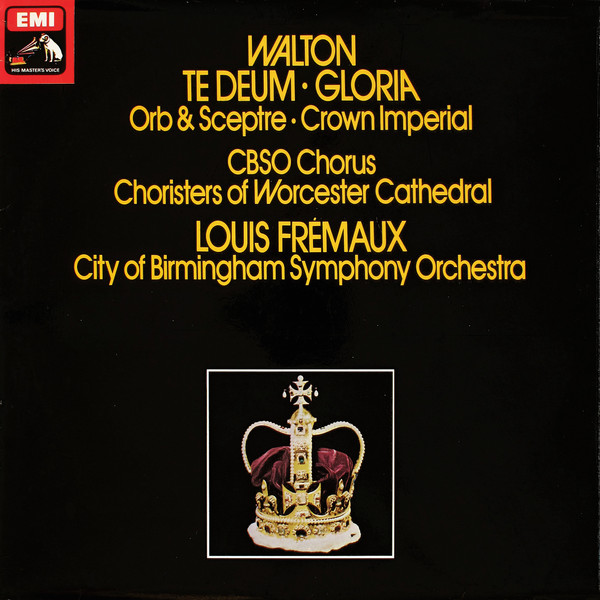

Walton: Coronation Te Deum; Gloria; Orb and Sceptre; Crown Imperial

And so to another exceptional record both sonically and musically, with performances as good as you can get. In 1969, in an unusual but inspired move, the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra appointed Louis Frémaux as its Principal Conductor. During his nine years at the helm he molded the orchestra into one of the best in England, and, as his successor Simon Rattle acknowledged in his famous remark, “the best French orchestra in the world.”

Throughout this time Frémaux and the orchestra made a series of superb recordings that benefitted from the very best of EMI engineering in the last years of analogue. Several of these records ended up on Harry Pierson TAS list of best-sounding records, but not, strangely, this one.

William Walton inherited the mantle of Elgar’s unofficial (later official) position as the go-to composer for Royal Ceremonial spectacles. Considered in his youth a modernist, Walton actually began his musical life more traditionally in 1912 as a chorister in Oxford’s renowned Christ Church Cathedral Choir. No doubt this is where he gained such an understanding of how to write so well for choral forces. He became an undergraduate at the University at the precociously young age of 16. His tutor pointed him in the direction of composers like Stravinsky and Debussy, and he inhaled all the modern music he could find in the Bodleian Library, to the detriment of the Greek and algebra knowledge he needed to graduate.

William Walton

William Walton

Oxford’s loss was London’s gain. Sent down without a degree, Walton fell in with the Sitwell family who took him in at their fashionable Chelsea abode. The eclectic Sitwells were the toast of London’s literary and creative society, and through them Walton met the greatest musicians of the age from Stravinsky to Schoenberg, Gershwin to conductor Ernest Ansermet. He also embarked on writing the music for a strange entertainment built around Edith Sitwell’s poetry, Façade (1923). This work gained both success and notoriety in equal measure for its curious blend of surrealism and whimsy, with the poems being spoken from behind a curtain through a megaphone while the musicians played Walton’s effervescent music. (Walton’s arrangement of two orchestral suites from Façade feature on another highly recommendable Frémaux/CBSO record).

Walton’s star began to rise in the 30s, and a particular landmark was the oratorio-cantata Belshazzar’s Feast (1931). For anyone used to the relatively sedate 2-hour-plus choral works of Bach, Handel, Mendelssohn and Elgar, this 35-minute evocation of violent, sexual paganism and divine retribution, requiring a massive choir and orchestra, with nods to jazz in its overtly modernist (albeit tonal) musical idiom, must have felt like they had been dunked in the ice floes of the Arctic Ocean.

The work was a grand success, and an early champion, Sir Malcolm Sargent, conducted it around the world. Even as incongruous a supporter as the great German conductor Herbert von Karajan conducted it, declaring it to be “the best choral music that’s been written in the last 50 years.”

So it can hardly have been a surprise when Walton was asked to write a March for the Coronation of George VI in 1937. He complied with Crown Imperial, a splendid updating of Elgar’s various Royal marches, with grand tunes aplenty, but cast in Walton’s immediately identifiable, more contemporary idiom.

When it came time for George’s daughter Elizabeth to ascend the throne in 1953, Walton provided another march for the Recessional, Orb and Sceptre, and the Coronation Te Deum.

The Te Deum immediately conjures up Belshazzar’s Feast in its use of antiphonal choirs, plus brass and organ interjections (also a product of Walton’s imaginative use of the massive space of Westminster Abbey). There have been many fine settings of the Te Deum for coronations, but the Walton is, for many, simply the most regal and joyful. The exuberance is off the charts. It is a favorite of King Charles III) and will be performed at his coronation.

Characteristically, Frémaux is at pains to get the detail of the colorful orchestral writing fully across, and the tricky choral work is exemplary (you can actually hear the text!). And he keeps the momentum going. The recording, by Producer David Mottley and Engineer Neville Boyling, is without fault, balancing the huge forces to perfection.

Walton: Coronation Te Deum

Along with the two marches, we are treated to another fine later choral work, the Gloria, written in 1961 to celebrate the 125th anniversary of the Huddersfield Choral Society and Sir Malcolm Sargent’s 30th year as its conductor. Again, the work is characterized by colorful use of a huge orchestra, brilliant choral writing and rhythmic bite that couldn’t be more removed from the standard choral tradition. It all makes for a thrilling listen at home and will put your system through its paces. (UK pressings only).

If you are not CD-averse, track down the superb Frémaux/CBSO box set on Warner - it is worth every penny.

![]()

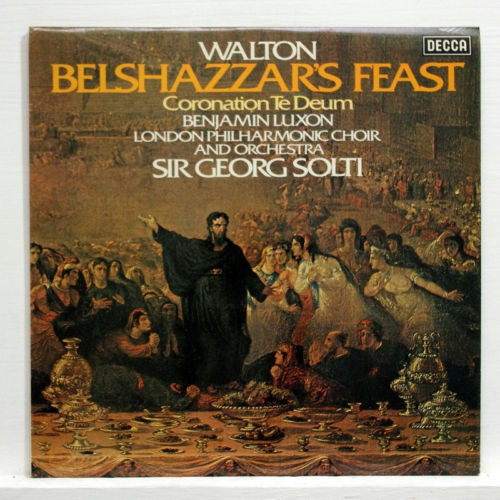

There is another fine recording of the Coronation Te Deum on Decca, with Georg Solti conducting the massed forces of the The London Philharmonic Choir and Orchestra, and the choirs of Salisbury, Winchester and Chichester Cathedrals.

Recorded (again) in Kingsway Hall in 1977 by Decca’s crack team of engineers Kenneth Wilkinson and James Lock, the sound has enormous impact and Solti’s characteristic drive and precision. For some the coupling of a fine Belshazzar’s Feast will be very attractive, though this performance lacks the lustre, jazziness and sheer sense of fun of Andre Previn’s classic EMI account, still my favorite.

Walton: Te Deum, Gloria, Orb and Sceptre, Crown Imperial

Barbara Robotham (mezzo-soprano), Anthony Rolfe Johnson (tenor), Brian Rayner Cook (baritone)

CBSO Chorus, Choristers of Worcester Cathedral

City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra conducted by Louis Frémaux

Recording Producer: David Mottley

Balance Engineer: Neville Boyling

Recorded in the Town Hall, Birmingham

EMI ASD 3348 (1977)

Music: 10 Sound 10

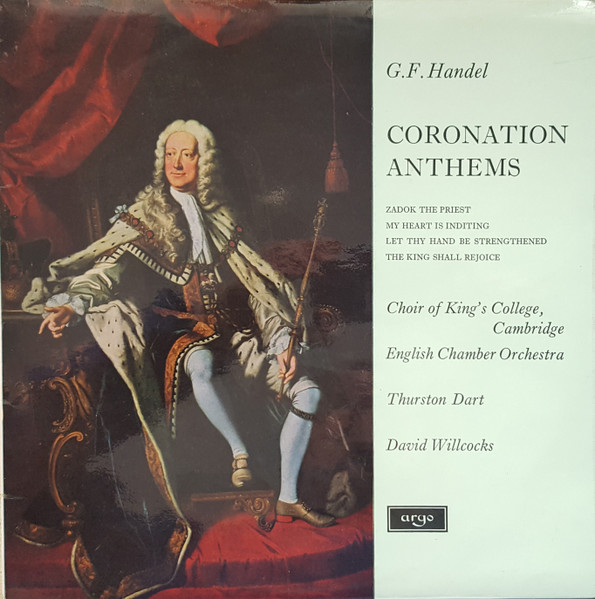

Handel: The Four Coronations Anthems, including Zadok the Priest

Next to Elgar, the composer most closely identified with music composed for the celebration of the pomp and splendor of Royal occasions was, in fact, a German (as is the House of Windsor itself, renamed from its original Saxe-Coburg-Gotha appellation in 1917 owing to anti-German sentiment during World War I).

George Frederick Handel made England his home in 1712 at the age of 27, and owing to his mastery of the newly popular operatic form (which he had studied in Italy), became famous and commercially successful of an order rarely seen by composers of the time.

So when it came to the coronation of George II in 1727 it was only natural that Handel would receive the Royal commission for four anthems to be performed during the service in Westminster Abbey. The first of these, Zadok the Priest, was so successful that it has been performed at the coronation of every monarch since that time. With its slowly-building introduction in the orchestra that erupts into a magnificent fortissimo with the entrance of the choir, brass and drums, Zadok the Priest has come to be closely identified with the essence of Kingship. It is a fantastic piece to sing, and made an indelible impression on me as a young chorister aged around 11 when I sang it in St. Paul’s Cathedral with a huge assembly of other choirs.

The extreme popularity of Zadok has meant that the other three anthems have been somewhat overshadowed, which is a shame since they are no less fine, with Handel applying his dramatic skills learned in the opera house to great effect. Fortunately, most recordings of Zadok also include the other three Coronation Anthems.

As you can imagine, fine recordings of this music abound, with British choirs of every size and make-up eager to bequeath their rendition to posterity. But I think most music lovers and record collectors would agree that the “ground zero” recording, as it were, is that of the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge, directed by its celebrated choirmaster, David Willcocks, recorded by Argo in the King’s College Chapel in 1963.

For generations, the King’s Choir has been considered the gold standard of Britain’s collegiate choirs: that is, choirs which are part of a University or Church institution, using all boys’ and men’s voices. When people talk about the quintessential English choral sound, this is what they are referring to. The presence of boy trebles on the top line, and of male countertenors on the second, alto line, lends a distinct sonority to the choir. The “King’s sound” is also partly defined by the vast space of the Chapel itself, which has a rolling reverberation of such length to prove immensely challenging to generations of recording engineers. (Certain King’s recordings, especially those with orchestra, have been recorded elsewhere for precisely this reason).

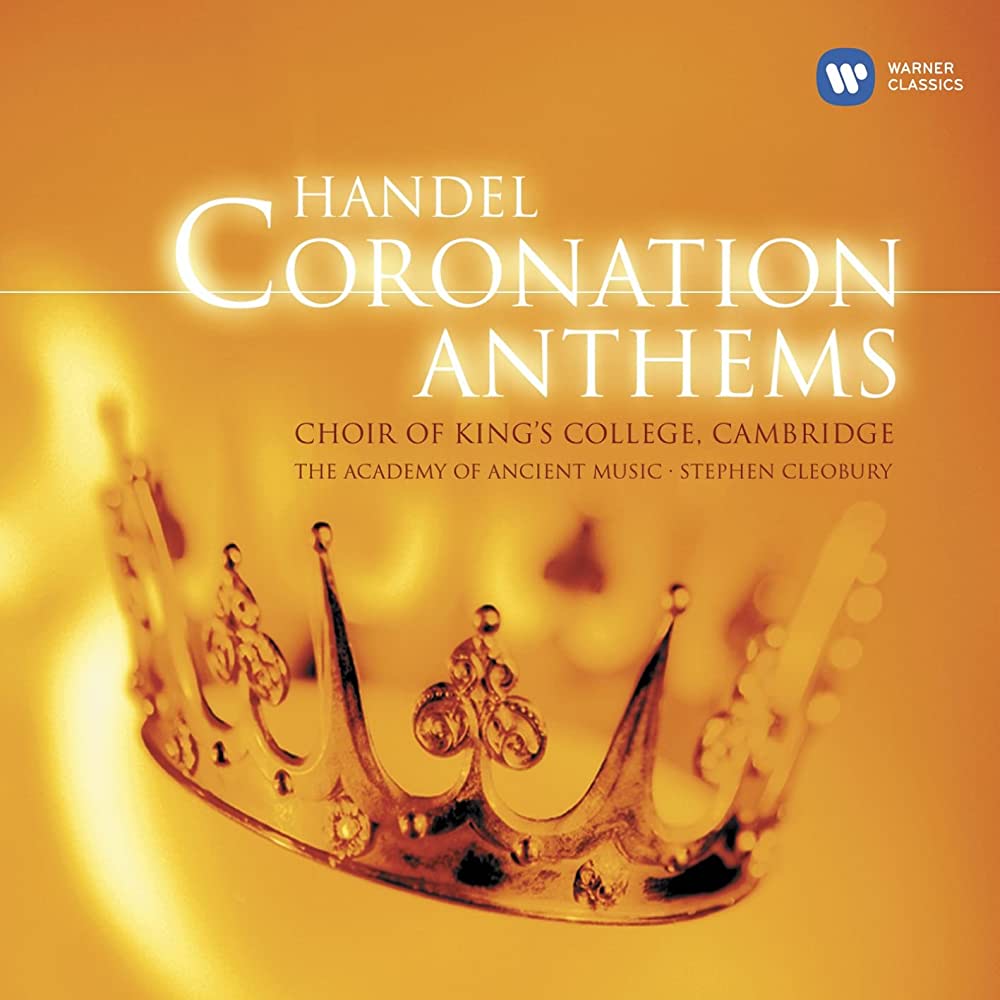

King’s has recorded the anthems at least twice, and the 1963 version is an acknowledged classic of the gramophone (UK or later Dutch pressings only). However, do not ignore the 2001 version under Stephen Cleobury (CD only): it has many felicities, and was recently selected as the benchmark version on BBC Radio 3’s Record Review. It is very fine indeed.

At Cambridge, the foremost rival to King’s is the Choir of St. John’s College which sings in a much smaller space. (Alas, to my knowledge the choir has never recorded these anthems). Historically, choirmasters here have nurtured a less “pure” sound than King’s, encouraging the boy trebles to adopt vibrato to enrich the sound. Interestingly, St. John’s recently announced that it was going to introduce girl sopranos into the choir, a development which some purists have greeted with appalled outrage. Given the fact that in recent generations boys’ voices have been tending to “break” at earlier ages, I can quite understand this decision. Of note: the long-time recent choirmaster at St. John’s, Andrew Nethsingha, whose series of excellent recent recordings on Signum Classics have shown the choir to be in fine fettle, recently took up the post of Organist and Choirmaster at Westminster Abbey, and as such will be leading the musical proceeedings at the Coronation Ceremony (along with Sir Antonio Pappano).

At Oxford, the main rivals to King’s and St. John’s are the choirs of New College and Christ Church. The recording of the Coronation Anthems on Hyperion by New College from 1989, available only on CD, has long been a top recommendation, paired with an equally splendid account of Handel’s Royal Fireworks Music (more of which in Part 2 of this survey).

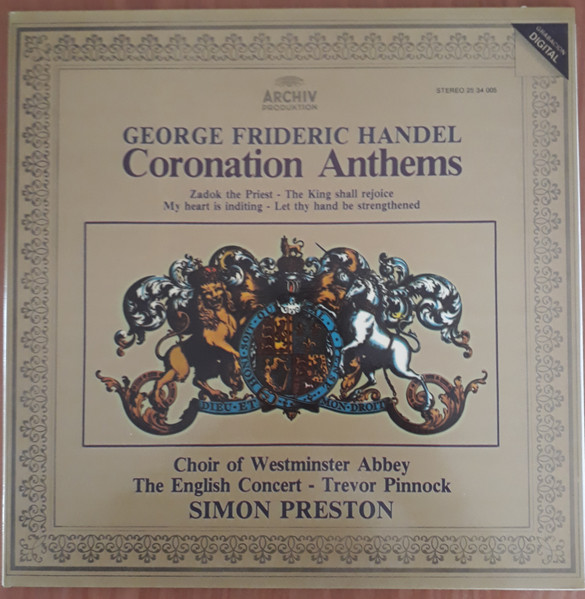

If you want to get a flavor of this music performed by the choir it was written for, look no further than Simon Preston’s recording with the Choir of Westminster Abbey on DG Archiv, issued on vinyl in 1982.

It was not recorded in the Abbey itself (another challenging recording space), but Henry Wood Hall provides a warm acoustic, and you get the period instrument stylings of the English Concert (Trevor Pinnock’s band), maybe the first recording of this music with such HIP forces. I have become more and more of a fan of the various period instrument recordings done by DG with the English Concert in Henry Wood Hall, even the early digital ones. In this case the smaller acoustic allows more of the choral and instrumental detail to emerge, and Preston (who trained the Christ Church Cathedral Choir for Christopher Hogwood’s seminal recording of Handel’s Messiah), demonstrates why he was one of the best choir directors of his time. There are no soloists, just select choir members used in solo passages. The performance is perfectly paced, with great affection shown in the more subdued My Heart is Inditing (honoring the Queen). It is definitely a more chamber-scaled rendition even than Willcocks’ King’s version, but never lacks for grandeur in the big climaxes. It is my overall preference for a version on vinyl.

Handel: Coronation Anthems

Choir of Westminster Abbey, The English Concert

Leader and Organ: Trevor Pinnock, Simon Preston

Production: Dr. Gerd Ploebsch

Recording Engineer: Hans-Peter Schweigmann

Editing: Reinhold Schmidt

Editor: Roswitz Cervone

Recorded in Henry Wood Hall, 1981

DGG Archiv Produktion Digital LP 2534 005

Music: 10 Sound: 8

Coronation Music for King James II

In this fascinating but lesser-known recording of music for the coronation of one of England’s few Catholic kings, Simon Preston leads the Choir of Westminster Abbey in a series of fine anthems by John Blow and Henry Purcell, and by lesser-known composers like Henry Lawes, William Child and William Turner. It offers an opportunity to hear alternative settings to the texts used by Handel for his set of Coronation Anthems: Zadok the Priest, My Heart is Inditing, Let Thy Hand be Strengthened and The King shall Rejoice.

Excellent notes by musicologist Bruce Wood (who also writes the notes for Martin Neary’s fine disc of Purcell featured in Part 2) set the scene for this lesser-known ceremony and its music. James II, being a Catholic, was at great pains to minimize the liturgical aspects of the ceremony, refusing to take communion in a service led by Church of England clergy. The Archbishop of Canterbury, in turn, attempted to sneak in that liturgy in the form of extra anthems!

Simon Preston leads the choir and period instrumentalists with all his customary aplomb. The recording, only ever issued on CD, is typical of the DG Archiv sound of the period. Not an essential acquisition, but of interest to Coronation completists.

Coronation Music for King James II

Choir and Orchestra of Westminster Abbey conducted by Simon Preston

Production: Dr. Andreas Holschneider, Charlotte Kriesch

Recording Supervision: Dr. Gerd Ploebsch

Recording Engineer: Hans-Peter Schweigmann

Editing: Reinhold Schmidt

Recorded in St. John’s Smith Square in 1986

DG Archiv CD 419 613-2 (1987)

Music: 9 Sound: 7

Continued in Part 2: Occasional and Ceremonial Music