Perfect Masters Thrive On Disasters: Brian Eno’s “Rock” Albums

From the archives: Michael Fremer explores Brian Eno’s four pioneering 70s “rock” albums.

(This feature originally appeared in Issue 7, Spring 1996.)

He didn’t play an instrument and he didn’t sing, but Brian Eno was in the band, and the band was Roxy Music. So what exactly did Eno (full name Brian Peter George St. John de Baptiste de la Salle Eno—wouldn’t you shorten it?) do for Roxy Music, which he co-founded in London with Bryan Ferry back in 1972? Listen to Stranded, the first Eno-free Roxy album and you’ll hear something missing. Or, listen to the pre-Eno U2 albums, and then to The Unforgettable Fire, the first Eno-produced U2 album, and you’ll hear something added.

Whether wearing eyeshadow, sequins and feathered boa or looking more like your mild mannered Uncle Fred (unless your uncle is a transvestite), first and foremost this former art student functions as a collaborator, a background manipulator, a theoretician, and a co-conspirator.

Snipping and pasting tape, looping circuitry, and prodding others, Eno has probably had a greater influence on the popular (and unpopular) music of the 1970s and beyond than many better known big name string benders, keyboard plunkers and loud mouthpieces. While the combined sales of the four “rock” albums Eno created between 1973 and 1977 probably totalled under 100,000 copies, the musical paths he cleared set wheels into motion that are still spinning.

How did this self proclaimed “non-musician” so profoundly affect three decades of music? As a British art student in the 60s, Eno became aware of the power of imagery and image manipulation. At the same time he was introduced to the works of minimalist and avant-garde composers like John Cage.

At a time when the image of the rock musician was straight-jacketed in the uniform of the long haired, bearded, flannel shirted, introspective intellectual—arguably a creation of John Lennon, another, older art student—Eno and Ferry were conspiring to turn the whole thing on its head.

In America, the war in Vietnam was raging, Nixon was President, and much of rock music had gotten serious and perhaps self-absorbed on both sides of the Atlantic. Even though the spirit of the late 60s “hippie” subculture had pretty much died out after Woodstock, the image lingered on, on the faces and bodies of a generation.

In those pre-MTV days, image was album art frozen in time and space. When Roxy Music appeared on the scene, it was an outrage, a sacrilege. These guys, with their makeup, slicked back 50s hair, and Halloween costumes were Sha Na Na, not serious musicians. Of course, in mocking the establishment, they knew just what they were doing.

Frontman Bryan Ferry, looked like Conrad Birdie, Eno, Carmen Miranda, saxophonist Andy Mackay some kind of jazz hipster, guitarist Phil Manzanera a cross between a rock musician and Vincent Price in The Fly. Only the rhythm section looked conventional, but the rhythm section was never at the heart of Roxy Music. It was mutable and disposable—so much so that the original British and American LPs of Roxy Music’s debut pictured different bass players.

Roxy Music was the first “art rock” band (or the second if you count Roxy’s inspiration, The Velvet Underground), whatever that meant, with retro-50s looks, and send-up messages about obscure dances (“Do The Strand”), love songs to blow-up dolls (“In Every Dream Home A Heartache”) and a return to an old-fashioned romanticism all but abandoned by the counterculture. Though much of the imagery and some of the music were rooted in nostalgia, the band, helped to a great degree by Eno’s experimental synth and tape recorder treatments, pointed toward the future—taking much of popular music there, even though Roxy’s own popularity was fleeting.

After the release of For Your Pleasure, Roxy’s second album, Eno and Ferry had a falling out. What had started out as art school humor turned too serious for Eno as Ferry got rock stardom of the brain (who can blame him?). Eno wanted no part of it, but he still wanted to experiment with music and with the electronic canvas, technology was rapidly making it available. Not being a musician, he sought the help of others on his first solo venture, including former bandmates Manzanera, Mackay and drummer Paul Thompson as well as King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp.

A month before beginning Here Come The Warm Jets, Eno and Fripp collaborated on (No Pussyfooting) (UK Island HELP 16, later UK Polydor Special 2343 095), an album of tape loop manipulations fed by a Gibson Les Paul, Fripp-designed effects pedals, Eno’s EMS VCS 3 synthesizer (which he’d used on the Roxy albums), a digital sequencer (remember this is 1973), and modified Revox A-77 reel-to-reel tape recorders. That album is best discussed in context of Eno’s other instrumental and “ambient” recordings.

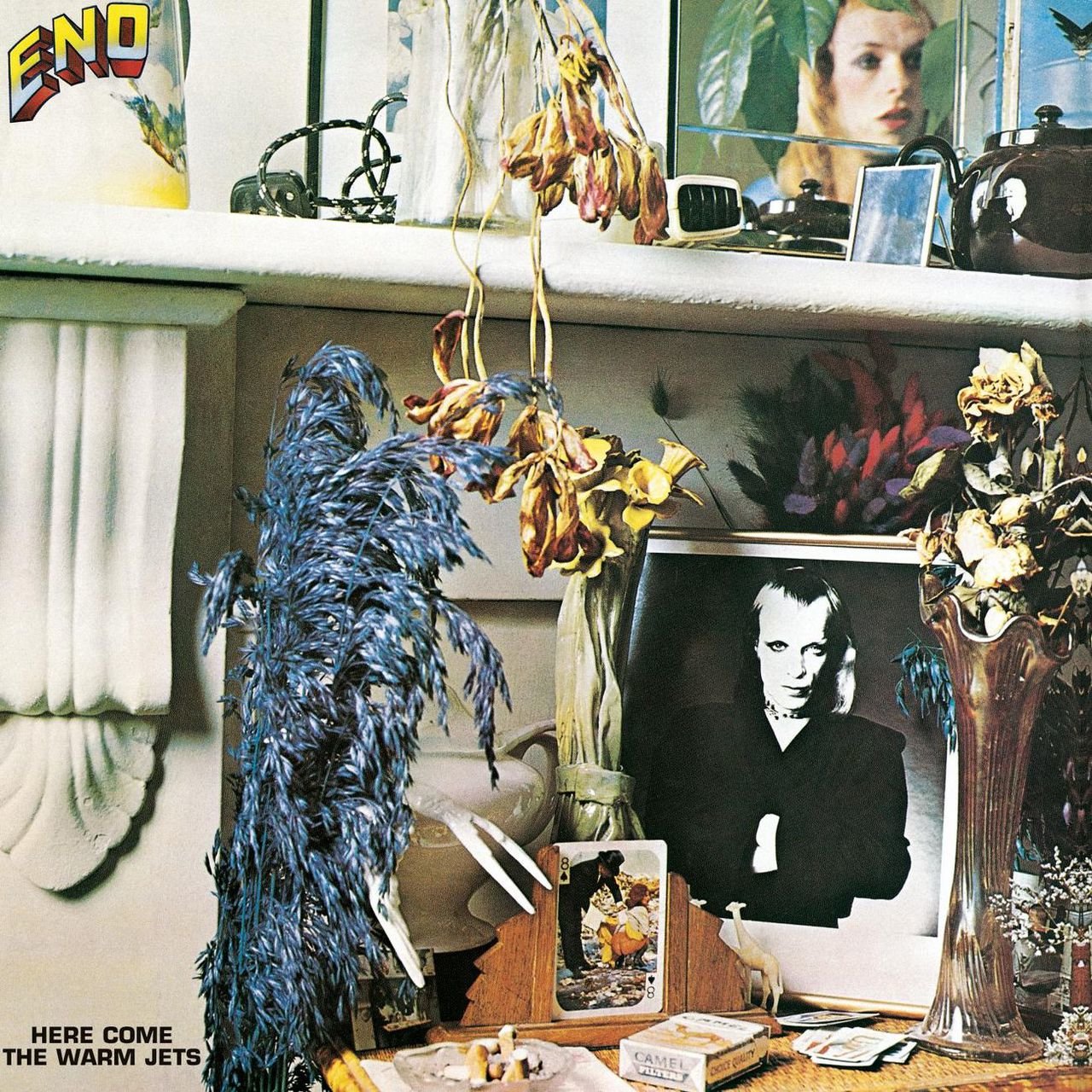

The Fab Four

Recorded in a month at Majestic Studios, London, September 1973 by Derek Chandler and mixed at Air and Olympic by Eno and Chris Thomas, Here Come The Warm Jets startled the lucky few who heard it. With its throbbing, jangling, postmodern Velvet Underground/surf guitars courtesy Phil Manzanera and Robert Fripp’s slashing, switchbacking, feedback-slewed guitar solos arching over odd, insistent rhythms—everything from Native American war dances (“Baby’s On Fire”) to modified Bo Diddley (“Blank Frank”) to upside down, backwards loops (“Driving Me Backwards”)—the record leaned more heavily toward “art” than “rock.”

Recorded in a month at Majestic Studios, London, September 1973 by Derek Chandler and mixed at Air and Olympic by Eno and Chris Thomas, Here Come The Warm Jets startled the lucky few who heard it. With its throbbing, jangling, postmodern Velvet Underground/surf guitars courtesy Phil Manzanera and Robert Fripp’s slashing, switchbacking, feedback-slewed guitar solos arching over odd, insistent rhythms—everything from Native American war dances (“Baby’s On Fire”) to modified Bo Diddley (“Blank Frank”) to upside down, backwards loops (“Driving Me Backwards”)—the record leaned more heavily toward “art” than “rock.”

There are songs of grand, sweeping drama (“On Some Faraway Beach”) and dissonant banks of repetitive noise (“Blank Frank”), there’s a VU tribute (“Cindy Tells Me”) and even a devastating Bryan Ferry kiss-off (“Dead Finks Can’t Talk”) in which Eno breaks into a mocking parody of the crooning baritone. And there’s something heartbreaking and inevitable about the title tune, “Here Come the Warm Jets” which is reputed to be about urine shower fetishists. “On Some Faraway Beach” has Eno imagining his own demise.

Sung in an arch, semi-precious, intellectual “proper” whine, Eno’s lyrics are dryly drawn, witty, and sometimes macabre. They can be simultaneously abstruse and brutally direct. What kind of rival does Eno face in the “paw paw Negro blowtorch”? I couldn’t tell you.

Here Come The Warm Jets sounds as musically and sonically audacious today as it did 23 years ago. Eno’s studio manipulations, the electronic atmospheres he created, the distortions, the vocal filtering and reverberant doubling, while technologically primitive by today’s standards, yield a tightly meshed sonic aesthetic only a visual artist could paint. Songs like “Baby’s On Fire” remain comfortably ahead of their time.

The mutating, alien electronic landscape is grounded in strong though sometimes oddly syncopated rhythms and a lyrical thread, which while seemingly specific, never locks fully into place. These are, after all, songs but contained within are musical cross breedings which yield bizarre and unexpected results (ie. the psychedelic/Indian/Rolling Stones mix on “Blank Frank”). You’re left chasing the same mysterious sensation with each listen.

The best way to experience Here Come The Warm Jets—and it ain’t even close—is on an original British Island “sunray” pressing (ILPS 9268). Next best would be the red label UK Polydor second press (2302 063), followed by the Japanese Polydor reissue (MPF 1168) and then the Caroline distributed EG Records CD (EGCD 11). Bringing up the rear is the original American Island LP (ILPS 9268)—not Sterling Sound’s most Sterling analog moment.

On the original British Island, the Polydor second and the CD, the sound is remarkably wide band and dynamic, with crisp and clean high frequencies, fast transients, and outstanding deep bass. The CD sometimes reveals heretofore hidden little details and instrumental lines, but at the expense of complex sonic and harmonic textures (compare Fripp’s monumental solo on “Baby’s On Fire”), image focus, soundstage depth and the overall musical drama. The Japanese pressing is of course impeccable, with a frequency balance and dynamic personality close to the British original, but somewhat more closed in and not quite as “fast” sounding at the very top.

The Japanese edition includes a hilariously incorrect lyric sheet (as many Japanese pressings do). On “Dead Finks Don't Talk,” Eno addresses Bryan Ferry: “Oh headless chicken/Can these poor teeth take so much kicking?”, which the Japanese translator Mieco Makino takes as “I was a headless chicken/Can this poultry take So Much Kicking?”.

I suspect Eno thinks the CDs are the way to go, but I could be pleasantly surprised. The American original is bloated in the midbass, lacking in deep bass and soft on top. Though I did not have an American pressed Editions EG vinyl copy (distributed by the late, lamented JEM Records) to compare with the others, it is very common in used record stores.

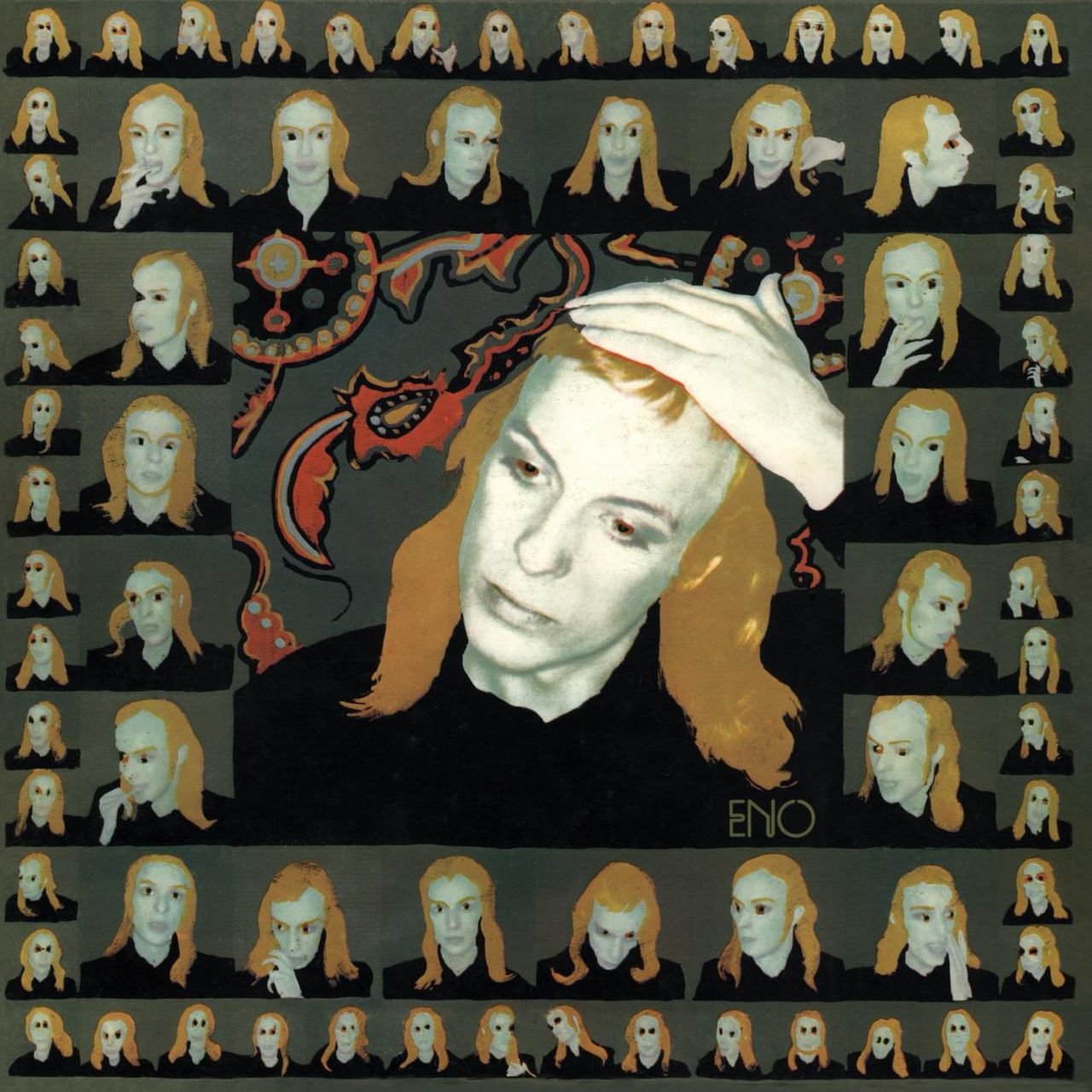

In 1974, Eno recorded and released his second solo album, Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), inspired by a set of postcards he came upon in San Francisco, which pictured scenes from a Chinese revolutionary propaganda opera by the same name, but without the parentheses.

In 1974, Eno recorded and released his second solo album, Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), inspired by a set of postcards he came upon in San Francisco, which pictured scenes from a Chinese revolutionary propaganda opera by the same name, but without the parentheses.

As on the first album, Eno’s musical and sonic palette covers a wide range of expression, though the album features an overall “concept”—a meandering spy drama filled with double dealing, microfilm, cryptic messages, a mysterious fat lady who could taste ingredients a spectrograph would miss, a duck that lays a gold egg which turns out to be wax, a strange group called the 801, a reference to Jonathan Richman’s Boston band The Modern Lovers, a whale with no eyes, an area in an orchard where people turn into crows, a picture postcard song about China and a denouement called “Taking Tiger Mountain” which ends with a long climb.

What does it all mean? It doesn’t matter and that’s the genius of it. Though lines connect, forming very specific pictures, they evaporate in a rush of new scenarios, all of which seems to add up to a coherent narrative, but doesn’t. Your mind’s eye inhabits a world of specific pictures just out of reach. That’s one reason this album also does not date, or become stale. Listening 20 years later continues to be a vital, fluid experience. Though I’ve combed the lyrics and dissected the sound, how Eno achieves that sense of continuous renewal remains difficult to analyze.

Eno again calls on Phil Manzanera’s guitar, adding Brian Turrington on bass, Freddie Smith on drums and Soft Machine’s Robert Wyatt on percussion and backing vocals. Guests like Andy MacKay, Phil Collins and others join the small combo on selected cuts, but despite the stability of the core unit from song to song, Eno’s sonic manipulations keep Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) from sounding like an ensemble album, though the core combo is evident throughout.

Eno sprinkles weird tape loops and processed sounds throughout the tracks, plus electronic drums (in 1974), fuzz bass, calliope, and synth distortions. There are repetitive, pulsating backdrops which subtly modulate a la Philip Glass and even a typewriter chorus on one track.

None of these additives are gratuitous. All have been splashed on the canvas with either meticulous care or deliberate chance. Eno is/was into process, experimentation, and letting tangents blossom. In the liner notes to Discreet Music (Obscure 3), Eno’s first “ambient” experiment released in 1975, he writes, “I have always preferred making plans to executing them, I have gravitated toward situations and systems that, once set into operation, could create music with little or no intervention on my part.”

While Taking Tiger Mountain consists of songs, not situations, it is clear that elements within the electronic orchestrations are the results of experiments and process strategies. The genius here is not that Eno was willing to experiment, but rather the way in which he’s incorporated the results into the finished product.

Some songs lurk, others rock, some are in your face, others in the mist. When you listen to “The Great Pretender,” note the way it builds: the treated piano (sounds like an old Ferrante and Teicher album Sound Proof, which was way ahead of its time) which calls out the rhythm, the ethereal, mysterious sounding treated guitars; the monolithic synth horns, the electronic crickets which eventually take over the mix, and consider that nothing on this track sounds recognizable as an instrument. Then consider the year: 1974.

Two standouts on Taking Tiger Mountain… are rockers: “Third Uncle” and “The True Wheel.” You can still hear the light going on in David Byrne’s head when he heard “Third Uncle”—probably while an art student in Rhode Island—and you can hear the direct connection between it and the Talking Heads’ sound.

As with Here Come The Warm Jets, the sonic hierarchy is original British “sunray” Island vinyl (ILPS 9309), the British Polydor reissue (2302 068), the Japanese Polydor reissue (MPF 1157), the Caroline/EG CD (EGCD 17) and finally the original American Island vinyl (ILPS 9309). And for the same reasons.

The sound, recorded by Rhett Davies at Island Studios, is even better than the first album, with wider frequency extension from top to bottom, a broad, nicely layered soundstage; and outstanding dynamic range. The drum sound is particularly well rendered, especially the snare. Much of the sonic goings on are artificial, electronic or processed, but the overall sound is warm, relaxed and tubey. While you’ll get good clarity from the CD, don’t expect the big, warm, easy sound the vinyl provides. What you’ll get is thinner and somewhat opaque, but it’ll do in a pinch.

Side one of both British pressings ends with a locked groove which will play electronic cricket chirping until you get up and lift the stylus. The CD lets it go for a very short time and then fades it out. To keep in the spirit of the original it should have been left going. I guess Eno didn’t supervise the transfer. The original gatefold packaging consisting of four prints from a limited edition lithograph by artist Peter Schmidt is another reason to get the LP. Again the Japanese pressing, also gatefold, has some funny mistranslations including turning “We saw the lovers, The Modern Lovers, and they look very good, they looked as if they could” into “We saw the bottles, the modern mamas….”

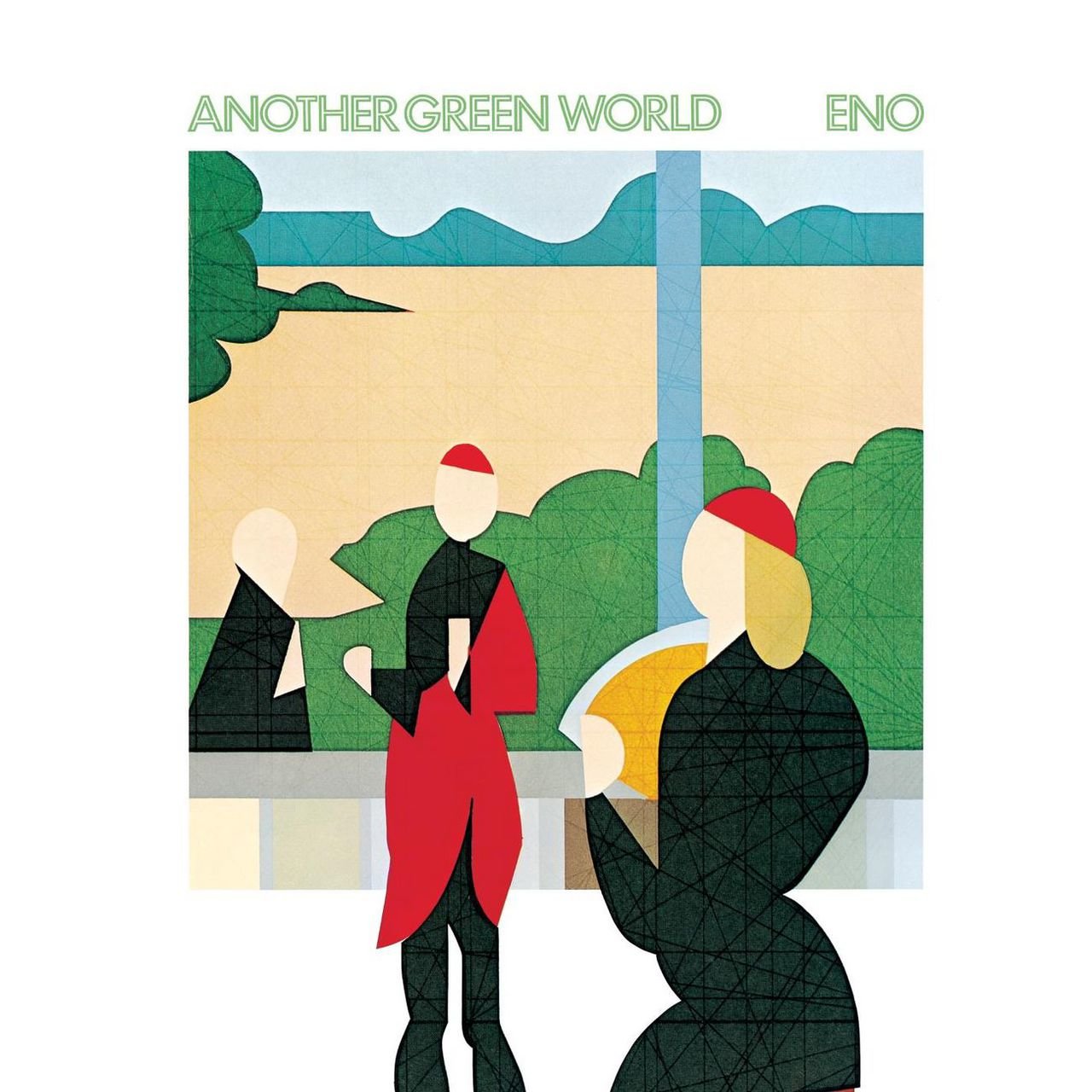

A year after Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) and worlds apart, Eno released what many consider to be his most innovative and evocative album, Another Green World. It took two months to produce—twice as long as each of the previous two albums. Though synthesizer based, the album sounds organic and almost leafy. The set of mostly short, prehistoric and tropical sounding instrumental collages marked a distinct turning point for Eno, a change which would eventually come to dominate his solo recorded efforts and profoundly affect his collaborations with others.

A year after Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) and worlds apart, Eno released what many consider to be his most innovative and evocative album, Another Green World. It took two months to produce—twice as long as each of the previous two albums. Though synthesizer based, the album sounds organic and almost leafy. The set of mostly short, prehistoric and tropical sounding instrumental collages marked a distinct turning point for Eno, a change which would eventually come to dominate his solo recorded efforts and profoundly affect his collaborations with others.

Before recording began, Eno and artist Peter Schmidt created a deck of cards which they called “Oblique Strategies.” The cards, each of which contained a specific instruction, were like a more sophisticated version of the old “Magic Eight Ball,” which only answered “yes” or “no.” The cards were more about exploring possibilities and choosing directions. Eno used them to help guide him in the production of the record.

For the first time, many of the tracks are all Eno—on “desert” guitars (whatever they are), synthesizers, Farfisa organ, and effects devices. On a few cuts, Eno is joined by Phil Collins, John Cale, Robert Fripp and other British “progressive” musicians. With the exception of two ballads, “I’ll Come Running” and “Everything Merges With The Night,” which are fully realized songs with vocals, the other tracks sound improvised, and more like segments which begin, build and then just trail off when whatever juice the experiment yielded dried up. Some are short fragments, others last longer.

Another Green World marked a sea change for Eno, musically and image-wise. Gone was the long hair, the makeup and the weirdness. Instead, the green-tinted monochrome back cover photo shows a contemplative, bare chested, rather delicate looking youth reading a book. Also gone were all musical references to rock’s strict time. Nothing on the record rocks. Some of the sonic miniatures are without rhythmic signatures, those with a beat are convoluted and heavily syncopated.

Having led a small but dedicated pop music audience to the edges of the avant-garde with his first two albums, here Eno pushed them overboard. Back in his art school days, he’d performed a 90-minute La Monte Young piece and built two versions of Drip Event, an avant-garde experimental work. On Another Green World, Eno presents rock listeners with few familiar guideposts, but the warm inviting sonic otherworld he creates helps settle them into the work.

The album begins with “Sky Saw,” an oddly metered piece featuring a percolating bass line over Phil Collins’ drum kit accompanied by angular crosscut “snake guitar” distortions played by Eno, a Fender Rhodes piano in the backdrop and a “heave ho” sounding viola section courtesy John Cale. Eno sets up his listeners for what’s to come with a short lyrical outburst: “All the parts turn to words/All the words grow to secrets/No one knows what they mean/Everyone just ignores them.” Lyrics worth considering when listening to all four of these recordings!

That said, the instrumental vignettes begin with “Over Fire Island,” a mysterious fretless bass-driven miniature, featuring odd sonic drive-bys: doppler effected synth fly-overs, and buzzing electronic hot plates punctuated by percussive drum drops. The piece neither ends nor begins, it just sort of pokes its head through the undergrowth, turns and disappears.

Next up is the album’s stunner, “St. Elmo’s Fire,” which features one of Robert Fripp’s most perfectly realized guitar solos, a cool, twisting, yearning figure that jumps and bubbles under and over Eno’s evocative lyrics set beneath a “cool August moon.” It’s a track that sounds best played on a hot summer evening, not surprisingly.

Of the four Eno albums covered here, Another Green World is the most visual and evocative. The sonic pictures painted are at once mysterious and familiar. It is as if Eno is putting sounds to the most basic and primitive thoughts and feelings we encounter in dreams and in the state between sleep and consciousness.

Using just a rhythm machine and simple synth chords, on “The Big Ship,” Eno conjures up a cathedral’s worth of basic human longings and feelings, building the piece to a sonic climax and then letting it slowly drift off and disappear. The listener is left frozen in the moment—at peace, yet unsettled.

After the lyrically enigmatic but musically conventional ballad “I’ll Come Running,” in which Fripp again provides a brilliant guitar counterpoint to Eno’s simple though lovely melody, the side ends with the title track, another short sonic experiment based on the simplest musical construct.

“Sombre Reptiles” sounds just like it reads, giving the listener the feeling that perhaps Eno too came away from the album feeling as if he’d created a modern day sonic Fantasia—at least that’s my take on Another Green World, an album with far reaching consequences for post-70s instrumental music, not the least of which was the creation of “Newage” as in “sewage” music.

It would be wholly unfair to blame Eno for that revoltin’ development as nothing here remotely approaches the treacly, “beautiful” so pleasant it’s unpleasant cornpone that is most of what’s called “New Age.” End editorial.

The sound on Another Green World, again by Rhett Davies (who co-produced the album with Eno), is a step above Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), yet again more dynamic, more sensational, with deeper bass, more liquid mid-bass, richer midrange and snappier and more extended highs without a trace of edge or brittleness. Occasionally some tape hiss intrudes into the picture.

Spatially, Another Green World presents a three-dimensional picture with superb front to back and side to side layering of sonic elements and a refreshing cushion of air. The organic feel Eno obviously went for is achieved in part by judicious use of reverb, which is never really expressed as an audible element as it was on previous Eno productions. Rather it is used to fill out space and add depth.

Depending on your system, you might prefer either the British Polydor Deluxe pressing (2302 069) or the Japanese Polydor (MPF 1153) which I replaced my British original with when it became available to me in the mid-80s. (Luckily, I found a British pressing recently for $6 at a used record store in Denver, CO.) I also have a blue label US Island pressing from the late 70s mastered by Sterling.

The British pressing has the most neutral tonal balance of the three vinyl versions I had on hand, with the sharpest and fastest high frequency transients. It’s a bit thin in the middle compared to the Japanese pressing, which gives the British stiff competition, though it’s a bit bloated in the midbass. Either one will do.

The blue label Island US is slow and sluggish on bottom and recessed on top. It sounds as if it was mastered using a poorly made transfer from a second generation tape. It is, however, inexpensive and easy to find at used record stores, as are later Editions E.G. pressings, one of which I did not have on hand for this story.

Be sure to check under both “Eno” and “New Age instrumentals” sections when you go looking for Eno. I’ve seen copies of all four of these albums filed both ways. If you’re embarrassed being seen bellying up to the “New Age” bar, wear an oversized hat. Eno albums do not belong in the “New Age” section for you used record store owners out there.

The Caroline/EG CD is very cleanly rendered, and as nicely balanced as the British original, but it’s somewhat drab and dry and two-dimensional compared to any of the vinyl. While it, and the other CDs, may have been generated from original master tapes, it sounds as if a less than stellar sounding analog deck was used for playback and an undistinguished A/D device did the conversion. Nonetheless I’d pick the CD over an American Island if that was the choice here.

Two years later Eno released his final rock album, Before and After Science. It was the longest gap between albums for Eno, not surprising when you listen to Another Green World. How do you top that?

Two years later Eno released his final rock album, Before and After Science. It was the longest gap between albums for Eno, not surprising when you listen to Another Green World. How do you top that?

What Eno came back with was a record which retained the synthesized, otherworldly jungle mystery of Another Green World while reintroducing the harder rocking elements of Here Come The Warm Jets and Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy). The album’s opener “No One Receiving,” with its insistent syncopated rhythm (Phil Collins on drums, Percy Jones on fretless bass) and oblique lyrical references to “these metal days” combines elements of both.

The second track, “Backwater,” an ebullient Eno tune, features a geopolitical storyline and uptempo music bed similar to “Third Uncle.” Backed by just bass and drums, the track illustrates the “non-musician”’s growing skills as a player and arranger.

“Kurt’s Rejoinder” with Percy Jones on “analogue delay bass” and Dave Mattacks on drums, echos rhythmic and sonic motifs from Another Green World but with vocals added, it presages Eno’s work with David Byrne on My Life In the Bush of Ghosts.

“Energy Fools the Magician,” a sonic miniature which sounds like an outtake from Another Green World, links “Kurt’s Rejoinder” with the album’s high energy point, “King’s Lead Hat,” which is an anagram for “Talking Heads.” Driven by Phil Manzanera’s barbed wire rhythm guitar and Fripp’s keyboard-like guitar solo, the song is rich with Dada-esque Eno-isms like “Splish splash I was raking in the cash,” “I count my fingers as night falls, and draw bananas on the bathroom walls” and “The killer cycles, the killer hurts [or is he saying kilohertz?], the passage of my life is measured out in shirts.”

Side two begins with “Here He Comes,” a melodic, delicate, almost syrupy mid-tempo ballad in the same spirit as “I’ll Come Running.” From there, the energy level and emotional texture of the record slows and cools like a descent into a dark cave beginning with “Julie With,” a drifting, dreamlike sequence.

Lowering the energy level even further is “By This River,” Eno’s collaboration with German keyboard minimalists Achim Roedelius and Möbi Moebius of the group Cluster. “No noise reduction systems were used,” the jacket advises, and you’ll hear some hiss on this slow, floating keyboard excursion with Eno’s lyrics casting a hypnotic spell over simple musical figures.

Taking down the flame yet another notch, “Through Hollow Lands,” dedicated to instrumentalist Harold Budd, paints a bleak, barren landscape washed over by a distant electronic wave. This track again points toward the future: to Eno’s epoch collaborations with David Bowie, particularly side two of Low.

Before and After Science ends with the simple hymn-like “Spider and I” with Eno singing over a slow, dreamy chord progression produced by a harmonically rich, distant synthesizer wash, accented with keyboard strings. As Eno sings “a thousand miles away,” the music bed begins to drift off, leaving the listener feeling empty as if they’re about to leave a special, magical place, and knowing no return is possible.

The sound on Before and After Science is even finer than Another Green World’s—particularly the snare drum and cymbals that sound engineers Rhett Davies and Dave Hutchins get at Basing Street Studios in London. So creamy, smooth and sweet sounding! On “Here He Comes,” Dave Mattacks’ rim shots and cymbal hits will kill you, they sound so real.

Bass is even deeper and tighter than on previous albums, and overall dynamics are greater. The quieter tracks on side two exhibit some low level noise and hiss, but who cares when what’s there is so fine? Top to bottom balance is superb, image focus is outstanding and the volume of air and space the soundstaging creates in your listening space will transport you to where Eno wants you to go. A magical record in every way, one which never fails to work its wonder every play. Hard to believe it’s been spinning on my turntable for almost 20 years.

The album’s subtitle is Fourteen Pictures, which refers to the 10 musical tracks and four color offset prints included in a slate blue folder in original British Polydor pressings (Polydor Deluxe 2302 071). The four photos are reproduced in black and white on the back jacket of original pressings, and in color on second pressings, with the text changed to alert you as to where you can send £1.50 for the four prints (no longer available, obviously).

Here it’s a toss up between the British original, second pressings and Japanese reissue (Polydor MPF 1131). The Japanese issue is superb and worth buying if one shows up. It features a gorgeous midband, ripe and liquid, with warm mid bass and very deep, tight lower bass. There’s a bit more hiss than on the original British pressing on the quieter tracks, but as usual, the pristine silence of the Japanese vinyl allows you to “see” deeply into the soundstage. Any of these pressings will give you the goods.

I’ve run into a surprising number of original pressings over the years, with the color prints in the jacket. I have three copies, two whole, and one where I’ve had the prints professionally mounted. All were purchased for $20 or under, one as recently as last year. A great investment in musical pleasure at twice the price.

The American original, on blue label Island (ILPS 9478), is Sterling’s best transfer among Eno’s first four solo albums, with good extension on top and decent bass, but it’s a bit forward in the upper mids and the physical fit and finish of American pressings of this era simply can’t compete with their foreign counterparts. Still, if you see an American pressing you’ll most likely find it for under $10. I didn’t have a later Editions EG pressing available for audition, but they usually go for under $5.

Here the original American pressing beats the CD, which while not terrible, lacks the chimey cymbal sound of any of the LP versions, is somewhat constricted in the midrange, has surprisingly thin bass, and is spatially flat and detail shy. There’s also much more audible hiss on side two, but without the extension on top the record has.

Overall, though the CD sounds drab and two dimensional compared to the vinyl, on its own it sounds pretty good. In other words if you’re one of our all digital readers, please don’t let this discourage you.

In 1986, EG Records, then marketed by JEM, issued More Blank Than Frank (EGLP 65) a 10-track compilation culled from these four albums by Eno himself, who stated on the jacket, “This selection of tracks is biased—towards my taste. Instead of trying to compile a representative sample, an historical archive, or a ‘best of,’ I just put together a record I’d like to listen to.”

So what’s on it? Side one consists of the gentle stuff: “Here He Comes,” “I’ll Come Running (To Tie Your Shoes),” “Everything Merges With The Night,” “On Some Faraway Beach,” and “Taking Tiger Mountain.”

Side two contains mostly rockers: “Backwater”, “St. Elmo’s Fire,” “No One Receiving,” “The Great Pretender” and “King’s Lead Hat.” Missing in action here is “Third Uncle.” An interesting set, but the sound is awful. I suspect it’s compiled from Sony 1610 digital masters.

Eno’s vocals can be heard on a number of other recordings, including on the first of two exceptional records he made with the group 801. One, 801 Live (British Polydor 230 2044/Japanese Polydor MPF 1101/American Polydor ??) issued in 1976, features a small combo consisting of Eno, Phil Manzanera, drummer Simon Philips, bassist Bill MacCormick, keyboardist Francis Monkman and guitarist Lloyd Watson. There are outstanding covers of Eno’s “Baby’s On Fire,” “Sombre Reptiles,” and “Third Uncle,” and Manzanera’s “Diamond Head” and “Lagrima,” as well as a fascinating remake of The Kinks’ “You Really Got Me” and a monumental cover of The Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows.” With Rhett Davies engineering you’re in for some great sound too. British, Japanese, American is the sonic order. I haven’t heard the CDs.

A second 801 album, Listen Now (1977), produced by Phil Manzanera (British Polydor Deluxe 2302 074/Japanese Polydor MPF 1117/American Polydor PD-1-6147—also on CD), with its dark, bitter, stripped-down songs of political paranoia is also worthwhile and very relevant in 1996, though Eno is a peripheral player.

The music is sophisticated, jazz-tinged rock, masterfully arranged and played. The lyrics could have been written last night. Guests include 10cc’s Kevin Godley and Lol Creme, one time Roxy member Eddie Jobson, Split Enz’s Tim Finn, Dave Mattacks and others. Engineered by Rhett Davies, it offers crisp, buttoned down sound, wholly appropriate to the enterprise.

In 1990, 13 years after Before and After Science, Eno released his next vocal album, Wrong Way Up (LAND 12 [British] LP/Opal Warner Brothers 9 26421-2 CD) a collaboration with John Cale. For those expecting more of the atmospheric mystery of the first four albums, Wrong Way Up was a disappointment. A mostly tuneful, straightforward pop record, with a strong backbeat accented by Eno’s electronic manipulations, only in retrospect, at least for this writer, does the appeal of the record surface.

Eno’s collaborations with Fripp, the German band Cluster, Harold Budd, and David Byrne, and his “ambient” explorations, Music For Airports and the others, as well as his many production credits are subjects for another story and another time.

For now, the legacy of Eno’s first four albums, and their influence and importance in the flow of popular music continues undiminished by time or changing fashion. With the resurgence of introspective, guitar oriented rock bands, Eno’s 70s explorations have even greater relevance today than they did a few years ago.

Whether those making the music know it or not (and I suspect many do), Eno’s sonic, musical and electronic experiments of 25 years ago can be heard in the ebb and flow of much of today’s “alternative” rock. The textures and sound, the rhythmic patterns and the verbal strategies Eno innovated will continue to influence future generations of musicians, so forward looking were his concepts and implementations. These four albums are indispensable.