Musical Nationalism: The Subject of the Latest 'Original Source' Reissues

Emil Berliner Studios tackles Dvořák and Grieg orchestral standards

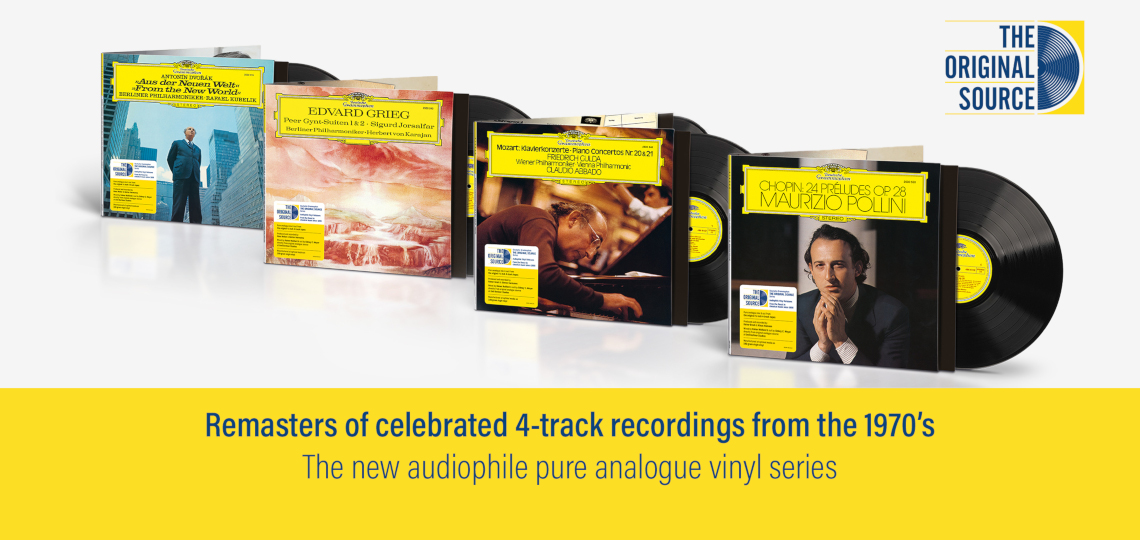

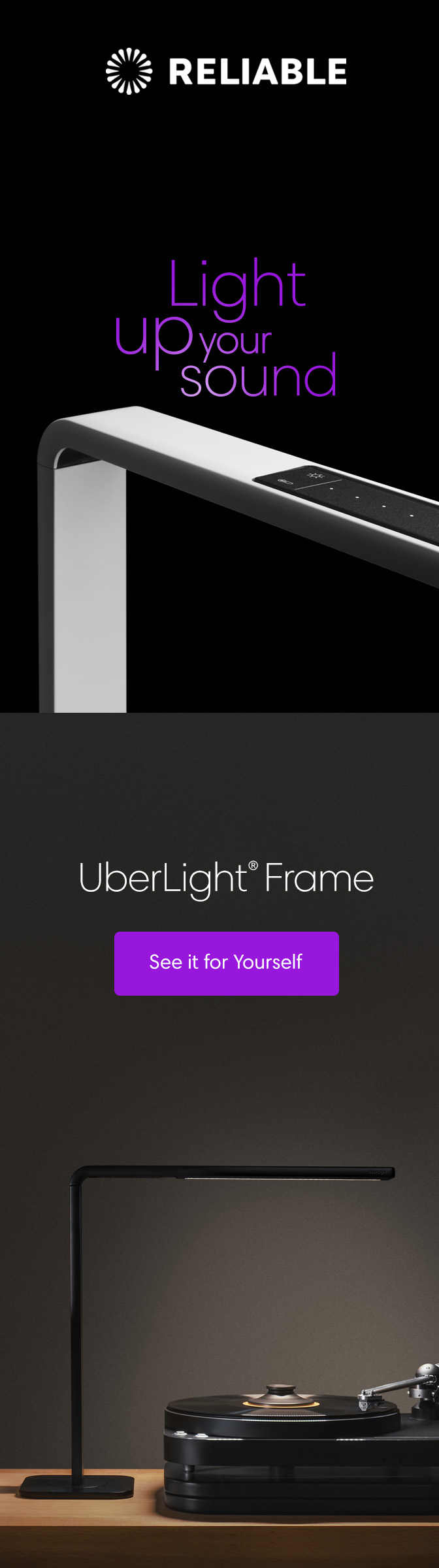

Four new ‘Original Source’ titles recently arrived on my door marking the start of fall, and the first new batch of releases following the company’s monumental Karajan/Bruckner box set reviewed here by my colleague Mark Ward. This batch fit nicely into two categories: symphonic orchestral works, and piano repertoire. This review will cover the just released two LPs of symphonic music.

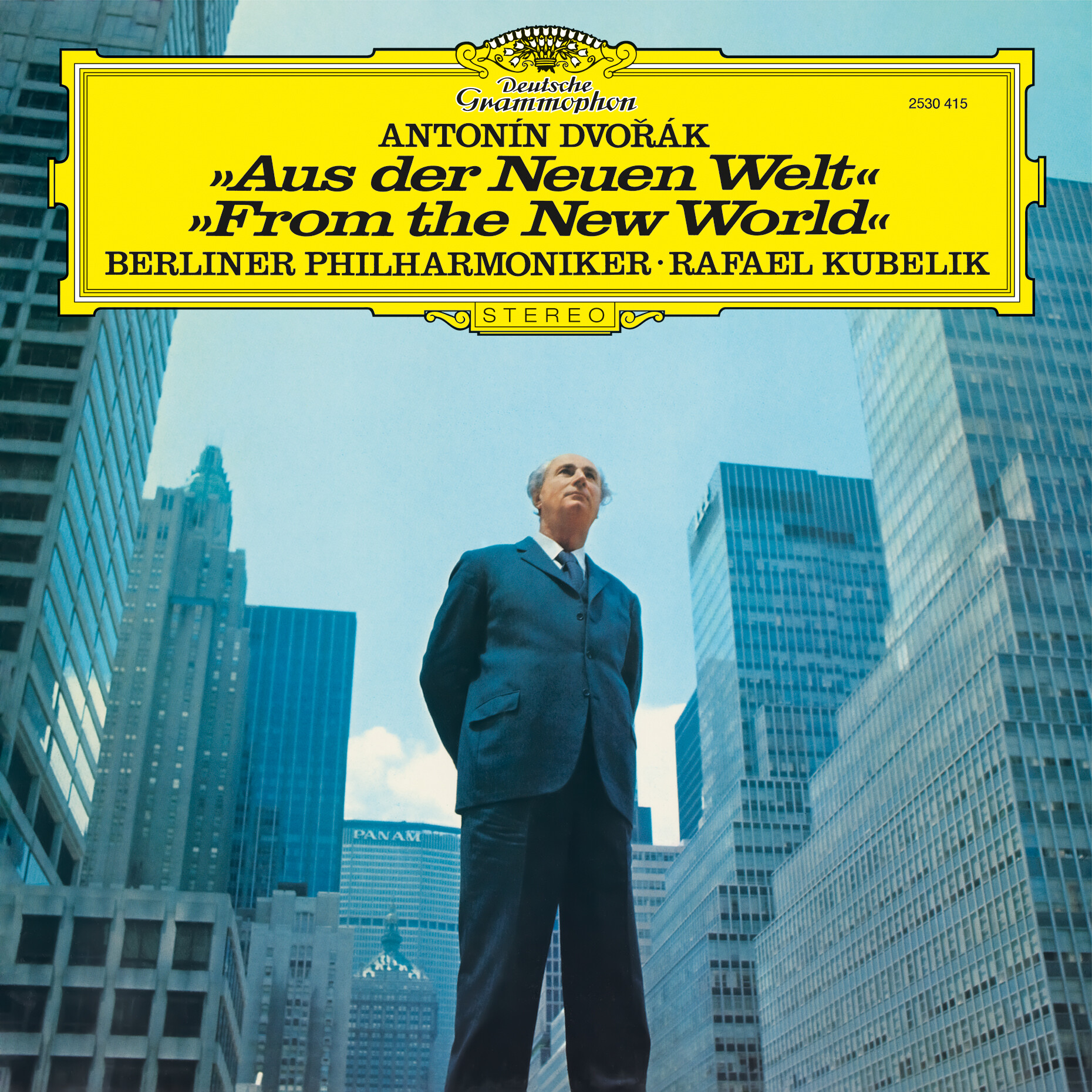

The first work needs very little introduction. If you are even peripherally aware of classical music, you’re probably familiar with Czech composer Antonín Dvořák’s most popular symphony, No. 9 in E minor- ‘From the New World.’ Even if you’re not familiar with it by name, you’ve probably heard the music before, either in its original form, from the song “Going Home”, which was composed after the success of the symphony, or in the music of numerous composers since, most notably American film composer John Williams, who took heavy influence from the melodies in this symphony in his scores for both "Jaws" and "Star Wars". Listen below to the powerful introduction of the 4th movement ‘Allegro con fuoco’, does it remind you of any iconic film music?

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) is the foremost composer of what we consider “Czech classical music.” His works were imbued with Czech folk melodies and his passion was to develop a compositional style highly distinct from that of neighboring Germany, of which it had a long history of being ruled by in various forms. By the time Dvořák finished his 8th symphony in 1889, he was immensely popular across Europe. It was in this context that Jeanette Thurber invited the composer to America to direct her new National Conservatory of Music of America, located in New York City.

Antonín Dvorak

Antonín Dvorak

In 1892 Dvořák set sail for the United States. His new teaching post gave him creative freedom (and a large salary), as well as summers off to compose and explore this strange new land. Within 8 months of his arrival on American soil, Dvořák had completed his 9th Symphony. I say 9th, but actually it was published as his 5th Symphony. You see, until the late 20th century Dvorak’s first four symphonies were never published. His first published symphony was actually his 5th (published under the name Symphony No. 1), so you will see many programs and records from the mid 20th century referring to this work as the Symphony No. 5 in E minor, but by the time the recording we have here was released, it had become his 9th Symphony.

The 9th is partially inspired by a poem from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow called The Song of Hiawatha, based on the oral traditions of the Ojibwe tribes of the Great Lakes. Dvořák was artistically inspired by his new home and wanted to incorporate folk musical themes from this new American landscape, which included inspiration from both Native American and Black American culture. This resulted in his seeking out baritone Harry Burleigh, an expert composer, archivist and performer of Black American folk music. Dvořák recognized this unique musical tradition far in advance of its ascendency in the early 20th century, stating: “I am now satisfied that the future music of this country must be founded upon what are called Negro melodies. This must be the real foundation of any serious and original school of composition to be developed in the United States.”

Dvořák borrowed no actual folk melodies from these American musical traditions, but he did try to imbue their qualities in his writing. Despite this, there is still the composer’s distinct Czech voice in this “American Symphony.” It is almost as if the composer is attempting to recreate those melodic patterns that he heard, but through a compositional style that without a doubt is Bohemian.

Czech conductor Rafael Kubelik is the maestro most often associated with Dvořák, and Czech music in general. He recorded the New World symphony numerous times in addition to the composer’s other symphonies, including a very early Mercury mono reading with Chicago just four years after his defection from communist Czechoslovakia. But far and away his most well-regarded performance of the work on record is his 1972 recording with the Berlin Philharmonic, the reading that now comes to us via the Original Source series. It has long been a critical darling and has stood out among a very crowded field. Why? Well in addition to Kubelik's obvious political connection to this work and his exile, he pushes the Berlin Philharmonic to give one of its most engaging, sensitive performances of the 1970s.

Unfortunately for Kubelik, the sound on this recording doesn’t match the detailed and sensitive performance. Berlin’s Jesus Christus Kirche had been the recording venue of choice for the Berlin Philharmonic since the early 60s, but it often presented sonic problems for recording engineers. The space has extremely tall ceilings and very hard surfaces. Unchecked, this can result in a very “bathroom-esq” sonic character, and unfortunately this recording has that in spades. I almost regretted listening to this on the (in for review) Raidho XT2 floorstanders, because while these speakers never sound harsh, they are so revealing of the source material that compromised recordings display all their warts in full HD. Playing this new original source pressing, much is revealed in terms of spaciousness and detail, but the sonic faults present in the original tapes cannot be overcome. If you thought the reverberant qualities of Kubelik’s Ma Vlast were too much in the OSS release from last year, you’re going to marvel at just how much echo is on tap here.

The Jesus Chrisus Kirche in Berlin, modern day

The Jesus Chrisus Kirche in Berlin, modern day

But that’s not the only issue, there is a distinct lack of any bass presence that corresponds to real instruments. The low brass sound thin, and the double basses sound like toys behind a curtain. There is occasionally the suggestion of bass, but it reveals itself as a sort of amorphous blob rather than attached to any instrumental voice. The most disappointing part was listening to the truly thunderous climaxes Kubelik was able to coax out of the Berlin players (particularly in the first movement), these fortissimo sections sounded dangerously thin and nasal.

I get why DG picked this LP for reissue—it’s one of their critically acclaimed darlings and a historic success for the label, but some recordings cannot be fixed by excellent AAA remastering, and this recording seems to be one of them. I have no doubt in my mind that Rainer and Sidney and the overall team at EBS heard these issues with this album and likely voiced their concerns to DG, but DG is not Analogue Productions, and there are probably more issues that go into a release aside from “does this sound awesome.” Eager for a version of this symphony that sounded a bit fuller and less abrasive, I scoured my catalog.

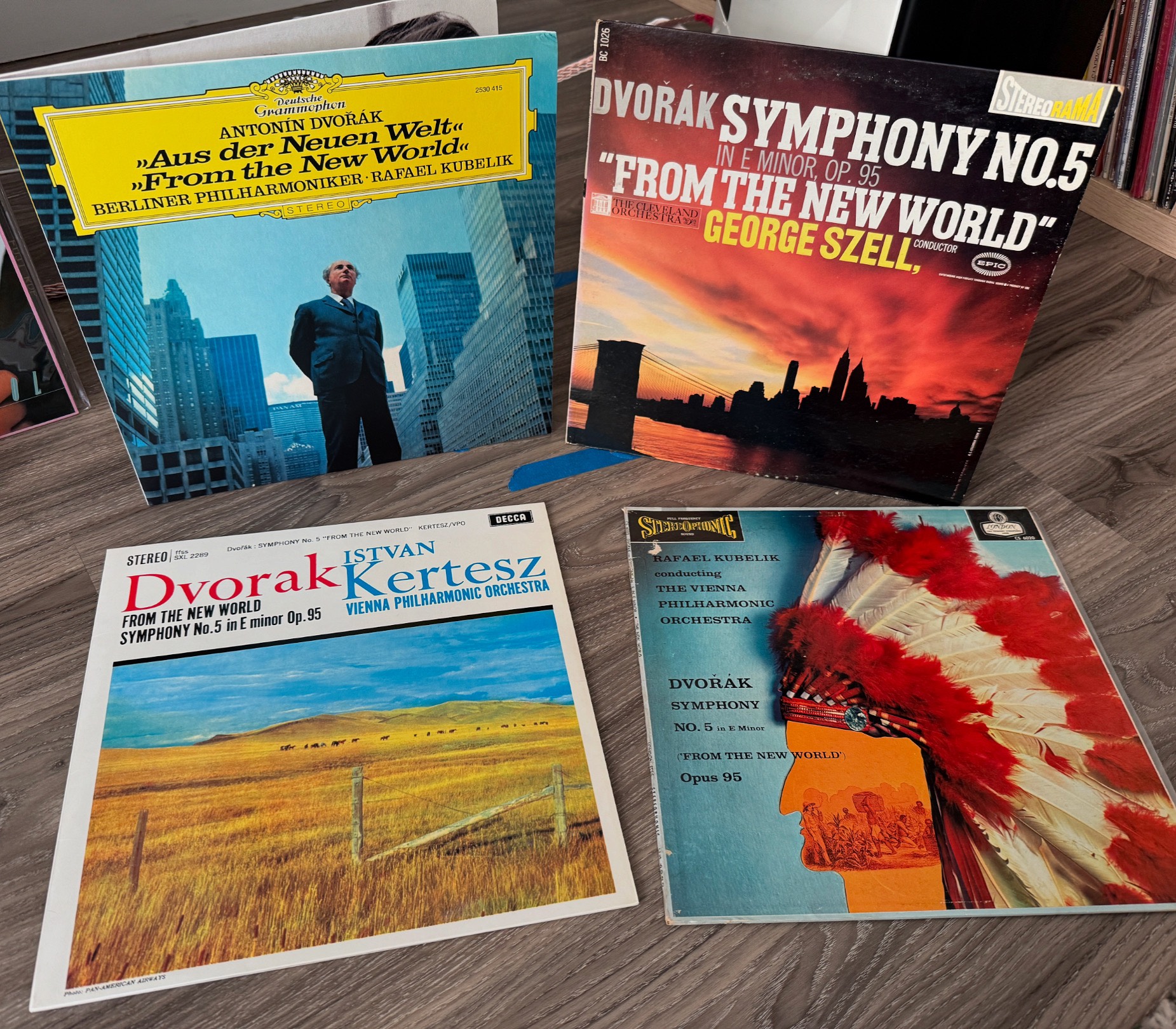

I cannot begin to review every single LP of this piece that exists, or even that I own. It’s one of the most-recorded symphonies of the 20th century and every single major conductor and orchestra has had at least one stab of it. For this review though I did pull out three other copies of note. First, Kubelik’s earlier and far less well-known outing on Decca with the Vienna Philharmonic from 1958 on a nice and clean ED1 London Blueback (CS 6020). The performance from Kubelik is great as his Dvorak always is, but the playing from Vienna at this time is just not up to the polished musicianship of Berlin. Further, the sound was far worse than even the DG; muddy, muffled, and with an astonishingly small and distant sound. I was simply not used to hearing Decca recordings from this era with such a veiled quality but as we know by now, they can’t all be gems.

Up next was another Decca recording, this time from István Kertész. Kertész, while not Czech like Kubelik, was in many ways a Dvořák specialist. He recorded the New World Symphony twice, one being this performance with the Vienna Philharmonic (SXL 2289), as well as a complete Dvořák cycle later in his career with the London Symphony (also on Decca). I don’t possess the later London recording (although I own Symphonies #7 and 8 from that cycle which are superb) but I do have a Speakers Corner pressing of the 1961 Vienna recording. This pressing by far had the best sound quality of the bunch, with excellent frequency balance, good sound stage, and very explosive dynamics. The reading is a bit more measured than Kubelik’s fiery rendition in Berlin, but it’s still finely played, and should scratch your audiophile “New World” itch (this recording was also reissued digitally sourced by Esoteric [ESLP-10002]_ed.).

I also pulled out a rather secret audiophile gem, a little-known recording from Jascha Horenstein and the Royal Philharmonic, recorded in 1962 by Kennith Wilkinson in the historic Kingsway Hall. “This must be a Decca wideband” you say. Well, no, this was very likely recorded for Decca but it only saw release as part of a large Reader’s Digest box set compilation in the 60s. It finally got a proper standalone release in 1977 when it was released on the budget label Quintessence (PMC 7001) (Chesky Records reissued this on CD and it can be had for a few dollars on Discogs_ed.).

I first heard this recording played by Angie of American Sound of Canada at Pacific Audio Fest 2023 on their intimidating Avant-Garde horn system powered by Phasemation tube amplifiers, and was amazed by the clarity and dynamics. I was further shocked when I found out you can buy this record for 5-10 dollars online, or find it commonly in many record shops “dollar bins.” While it might not have the artistic finesse of the Kubelik, this is a very fine performance with outstanding sound and is worth a try since the cost of entry is so low.

The real surprise however was my old Epic records pressing of the symphony performed by George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra (BC 1026). This performance has long been held up in the very crowded pantheon of Dvořák recordings as one of the greats, and it holds up to the hype. It’s quick, brilliantly executed, and full of passion. The surprising thing was how good my blue label Epic (not even a first issue) press sounded in comparison to both the Kubelik Decca and DG Original Source recordings. Could it top the Decca/Kertescz for transparency, dynamics, and bass response? No, but at least it didn’t sound overly boomy and had a nice level of instrumental clarity. It was a tad bright, as all these old Epic/Columbia titles tend to be, and there wasn’t much dynamic contrast, but the upside is that the double basses actually had resonance, the low brass had impact, and the timpani sounded like a timpani and not an empty soup can. If you’re looking for a bargain choice for this work, the Szell on Epic is a fine option and a recording you should definitely hear at some point. It may very well represent the best American interpretation of this somewhat American orchestral war horse.

For those wondering if this new Kubelik reissue is worth your time, I’d say go for it only if this recording is near and dear to your heart (it is after all, an important one), but it’s a performance-only buy in absolute honesty. The sound is far below what we’ve come to expect from this series and if you’re a casual fan you’re far better off grabbing the Speakers Corner Kertesz second hand for about the same price, the Horenstein for half of that. Or you could grab the Szell for less than 5 dollars and have just as great of a performance with sonics no worse than this “audiophile” Kubelik remastering.

Music: 10/11

Sound: 7/11

To bring up another symphonic purveyor of national folk traditions, we have a disc of music from the Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg (1843-1907). Grieg, like Dvořák, made extensive use of folk melodies from his homeland in an attempt to bring about a national music identity for his country on the world stage. He is best remembered today for two works: his Piano Concerto in A minor, and his incidental music to accompany the play Peer Gynt by fellow Norwegian Henrik Ibsen.

Grieg’s Peer Gynt music has gone on to yield some of the most dramatic and easily identifiable vignettes in the repertoire, most notably the opening “Morning” movement (you’ll know it immediately once you hear it), and the action-packed “In the Hall of the Mountain King.”

Ibsen asked Grieg himself to write music for his play, which premiered alongside Grieg’s score in 1876 in Oslo. The complete incidental score of this work includes 26 musical numbers including some choral and vocal movements. That complete score does have a number of recordings worth hearing, although few play the entire score, most take their pick of selections. But two versions to watch out for are an excellent Decca recording by Oiven Fjeldstad (SXL 2012/CS 6049) and a long highly regarded reading by Sir Thomas Beecham on HMV (ASD 258, or the much cheaper and just as good Hi-Q: HIQLP002).

However, Grieg himself prepared his Peer Gynt score into a set of two concert suites some years later in 1888 and 1893 respectively, and it is these versions most often programmed in concert today. Suite No. 1 contains the most easily recognizable material, but don’t discount the music of Suite No. 2, as it is filled with expressive melodic material, the kind of thing Karajan excels at, as well as moments of explosion and power, particularly in “Peer Gynt’s Homecoming.”

Also contained on this release is a much lesser known suite of incidental music, music for the play Sigurd Jorsalfar by Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (say that five times fast), about the life of king Sigurd I of Norway. The full score debuted in 1872, but like Peet Gynt, Grieg would later compile the music into a short suit in 1892.

Medieval depiction of Sigurd I of Norway

Medieval depiction of Sigurd I of Norway

This the first time I was introduced to this music and while Sigurd Jorsalfar lacks some of the emotional drama found in Peer Gynt, it’s a brilliantly orchestrated glimpse into a Norwegian composer’s attempt to invoke the mystical past of his nation (much in the same way other nationalist composers were proceeding in the late 19th century). It’s not essential repertoire but it rounds out the disc nicely with some memorable melodies and is much more interesting than the typical showy overtures Peer Gynt is often paired with.

Overall, Karajan and Berlin excel at this music, and the conductor maintains a level of expressive control over the orchestra throughout that few can rival. Karajan, despite being associated his entire career with German music and the German orchestral tradition, really shines with Scandinavian repertoire. This is evident in his Sibelius recordings which are some of the best. Karajan never overplays his hand with wild tempo choices, nor does he allow the music to get stuck in the mud, and the result is a tension in the music that keeps the listener engaged. The playing from the orchestra is likewise incredibly fine, with impeccable intonation and well controlled dynamics.

The sound here is another Jesus Christus Kirche production, with a very wet reverb. However this outing fairs much better than Kubelik’s Dvořák. One possible reason might be different producers for this session, where Werner and Wildhagen handled production and tone control for the Kubelik, here those credits go to Hirsch and Hermanns.

Compared to the Kubelik, bass here is actually present, and there is a fair bit of body and slam to impactful moments in the score. There are still some issues, the timpani still sounds a bit tin can-esq, and there is a lot of “tail” to the wetness of the space. But those issues were relatively minor, and I quite enjoyed the rich, deep, and detailed presentation of this Original Source pressing. I could actually hear the woodwinds, which is always a good sign in a Karajan recording, and the orchestra sounds nicely balanced with a fairly deep soundstage.

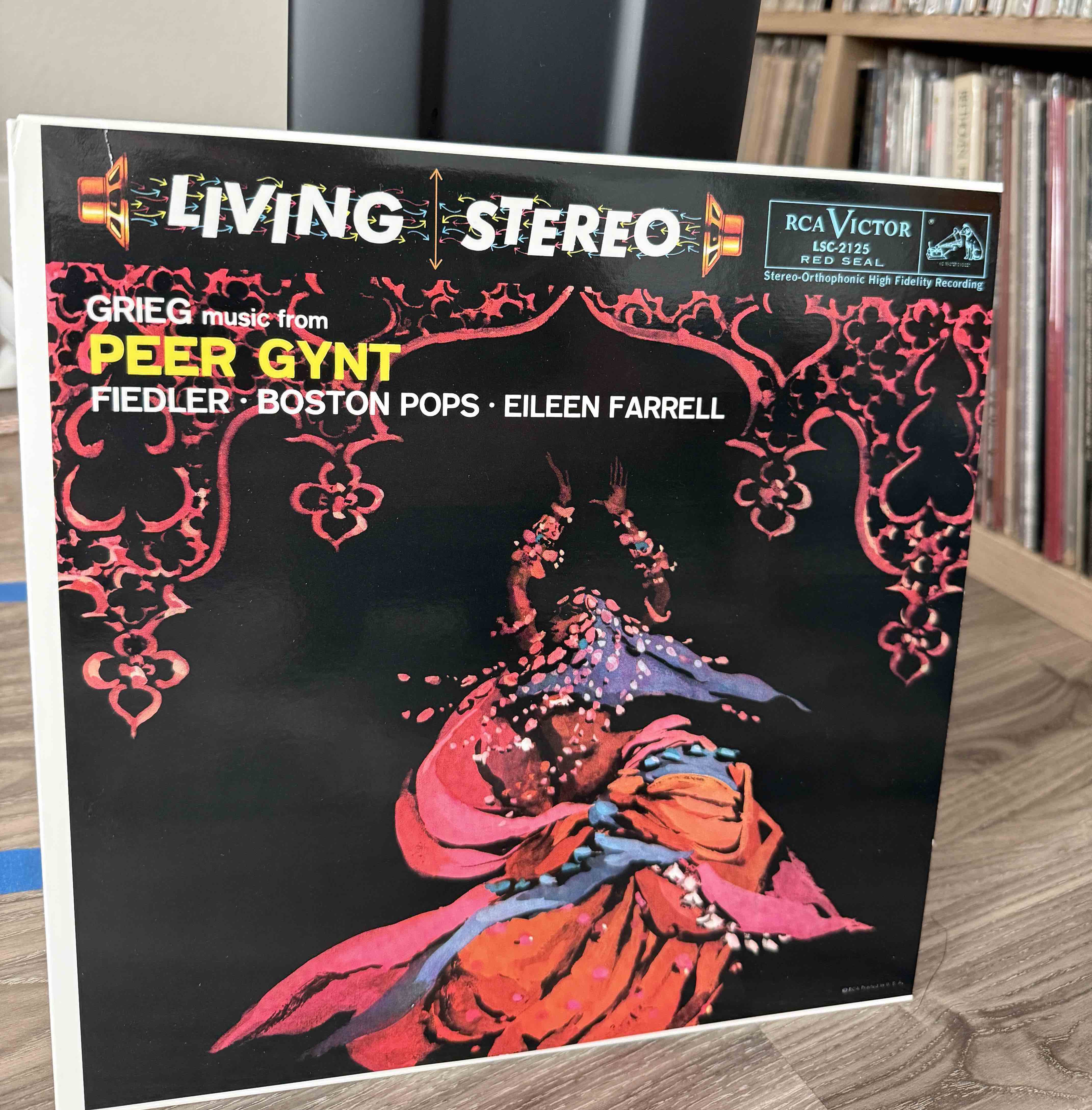

Obviously I didn’t have any recordings to compare for Sigurd Jorsalfar, and the aforementioned Peer Gynt recordings were not of the suites. But I do possess one great recording of both suites, a long out-of-print Cisco reissue of Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops on RCA Living Stereo (LSC-2125). The reading is great, but it’s a bit straight-ahead, and lacks a bit of the super nuanced musicianship the Berlin Philharmonic players bring to the table. The Bostonians make up a bit for it in power and energy, but overall I found myself preferring the performance on Deutsche Grammophon.

In terms of sound, the Cisco/RCA did have some clear advantages, including more string transparency, better bass slam and definition, and a more balanced “open” sound. Much of this may be due to the recording location, but there’s still a lot that I have to credit to that classic RCA Living Stereo magic. Few recordings get the string tone so right like these do. So yes the Cisco does present a more audiophile picture, but it didn’t embarrass the DG, and that’s a good thing.

While I was wary of recommending the previous Kubelik release due to its sonic problems, this record of Karajan conducting Grieg is much more worthy of your time. It’s one of the top performances available new or used, and the sound, while not earth shattering, is pleasant, satisfying, and brings the power when required. If you can tolerate the slight wetness of the recording, you’ll likely find it a thrill to listen to, just as I did.

Music: 10/11

Sound: 9/11