More Buried Treasure Emerges in the Latest Batch of Deutsche Grammophon "Original Source" Vinyl Reissues - Part 2

I follow up on two more "Original Source" reissues hitting the shelves later this month

After my last harrowing adventure through Deutsche Grammophon’s “Original Source Series”, I was hoping this next batch would prove less problematic and more up to the standards of what I had appreciated about the first few releases in the series such as the excellent Abbado Rite of Spring. Fortunately, with these two particular titles set to release officially on October 20th, my fears were abated. My colleague Mark Ward has already reviewed the romantic era thrillers of Berlioz and Beethoven, and left the more subtle works of Smetana and Mozart to me, so let’s dive right in.

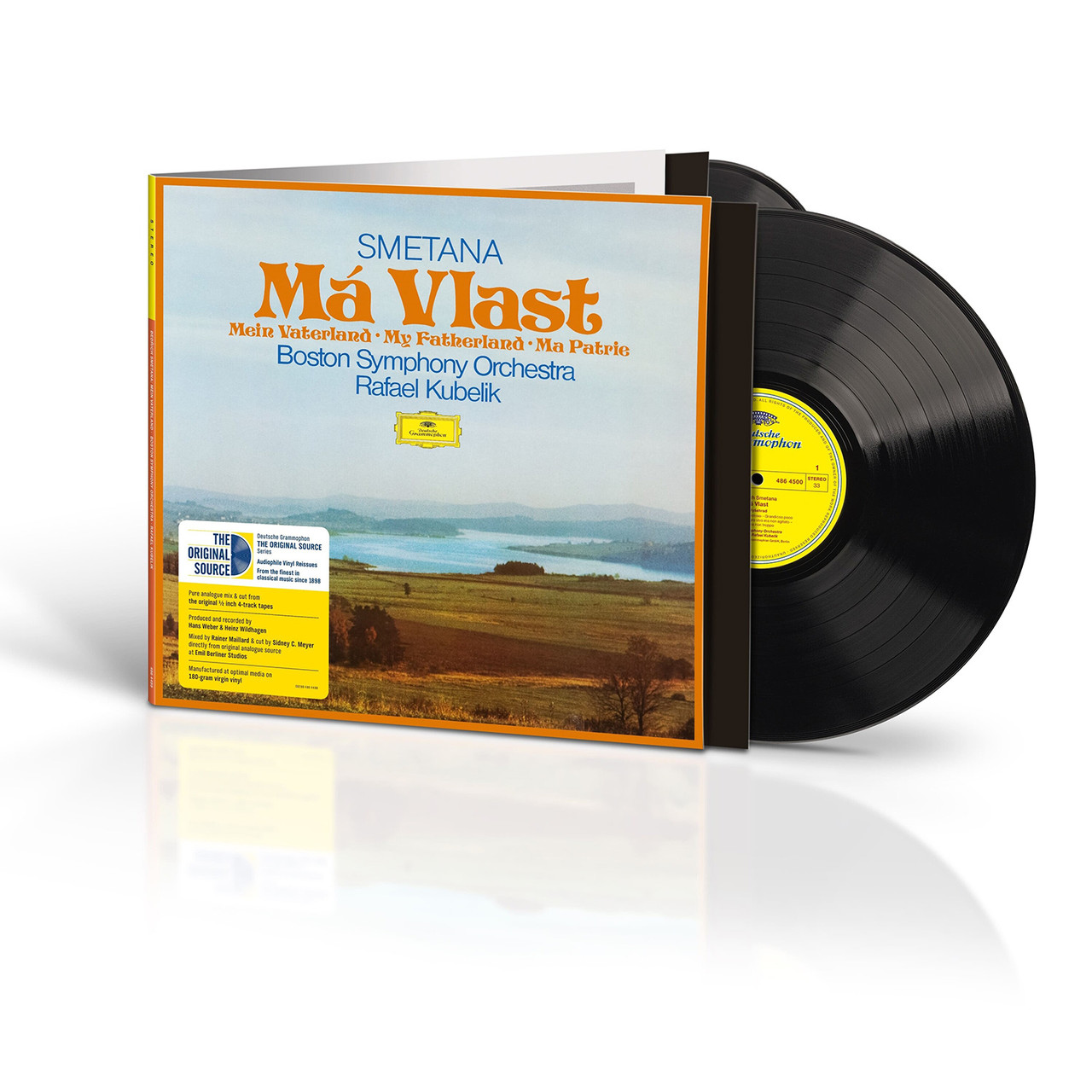

Bedřich Smetana- Má Vlast

Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Rafael Kubelik

Production and Recording Supervision: Hans Weber

Recording Engineer: Heinz Wildhagen

Recorded in Boston Symphony Hall, March 1971

Reissue mixed by Rainer Maillard & cut by Sidney C. Meyer directly from the original analogue source at Emil Berliner Studios

180g Pressed at Optimal

Limited Edition of 3000

For most casual classical listeners today, the composer that comes to mind when you think of Czech music is one Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904), the composer of the New World Symphony, Slavonic Dances, and the Cello Concerto in B Minor. But Dvořák’s world famous brand of symphonic Bohemian folk music would have likely never come to pass were it not for the pioneering vision of another Czech composer: Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884).

Composer Bedřich Smetana

Composer Bedřich Smetana

Smetana was the pioneering musical voice of Czech composers. He grew up in Litomyšl deep in the heart of Bohemia, but under the shadow of the Austrian Habsberg Empire. Because of this, he did not grow up speaking Czech, but rather German, as that was the language of day-to-day business for the middle class. Introduced to music at a young age by his father, he began studying piano and violin in multiple schools as both he and his family moved frequently. After arriving in Prague in 1839, he had the chance to hear a performance by the young Franz Liszt which inspired him to take up life as a professional musician. He was further influenced by the nationalistic uprisings of 1848 (in which he briefly took part) that ignited his passion for a specific Czech identity in music.

Smetana did not have an easy life, and his musical output was strained both by musical politics, and by his own health. Only two of his compositions ever gained sustained popularity; his opera The Bartered Bride, and his set of six symphonic poems titled Má Vlast (“My Homeland” in English). The work composed between 1874 and 1879, is a collection of short tone poems describing either specific landmarks in Czechia, or in the case of “Šárka” and “Blaník”, Czech folktales.

Despite being a Czech nationalist composer, Smetana encountered pushback for his musical style, primarily due to his self described “Wagnerism” that sought to meld Czech music to Wagner and Liszt’s compositional techniques and tone painting. Liszt’s tone poems in particular were an inspiration to Má Vlast, but where Liszt’s poems would employ one constantly changing musical theme per work, Má Vlast linked multiple small and large themes, much like Wagner’s Leitmotifs, that would reappear throughout the works.

The Six Poems of Má Vlast are as follows:

1. Vyšehrad (The Upper Castle)- This poem describes a historic 10th century castle in Prague situated the bank of the Vtlava River. Smetana himself described this movement in writing: “The harps of the bards begin; a bard sings of the events that have taken place on Vyšehrad, of the glory, splendor, tournaments and battles, and finally its downfall and ruin. The composition ends on an elegiac note”

2. Vltava (known more commonly as The Moldau)- Vltava is the aforementioned river that is also the principal river of the Czech Republic. In 1870 Smetana took a country river voyage down the river and was inspired by both the river and the sights he witnessed on the way. Smetana wrote in the score: “Two springs pour forth in the shade of the Bohemian Forest, one warm and gushing, the other cold and peaceful. The forest brook, hastening on, becomes the river Moldau. Through thick woods it flows, as the gay sounds of the hunt and the notes of the hunter’s horn are heard ever nearer. It flows through grass-grown pastures and lowlands where a wedding feast is being celebrated with song and dance. At night, wood and water nymphs revel in its sparkling waves. Reflected on its surface are fortresses and castles —witnesses of bygone days of knightly splendor and the vanished glory of fighting times. At the St. John Rapids, the stream races ahead, winding through the cataracts, hewing out a path with its foaming waves through the rocky chasm into the broad river bed —finally, flowing on in majestic peace toward Prague and welcomed by the time-honored castle Vyšehrad. Then it vanishes far beyond the poet’s gaze.”

3. Šárka- This poem is named for the female warrior from the classic Bohemian folktale The Maiden’s War in which an 8th century army of women warriors led by Vlasta rebel against Přemysl, the male widower of their fallen female ruler Libuše. Šárka is Vlasta’s lieutenant and lays a trap on a battalion of male warriors, pretending to be an imprisoned victim of Vlasta’s rebellion. Ctirad, the leader of the battalion, falls in love with Šárka and believes her tale, but is then betrayed when Šárka drugs his men with sleeping potion and sounds the horn for her comrades to slaughter the sleeping men.

4. From Bohemia's Woods and Fields- The least specific of the subjects in Má Vlast, Smetana intended this movement to depict rural life in the countryside of Bohemia. He writes: "This is a general impression of the feelings aroused on seeing the Czech countryside. Here, from all directions, fervently sung songs, some cheerful and others melancholy, resound from the groves and meadows. The woodlands (in solos for the horns), the gay, fertile Elbe lowlands and various other parts besides, are all celebrating.”

5. Tábor- This tone poem depicts the city of Tábor, south of Prague, known for being the center of the 15th century Hussite rebellion. This movement led by Jan Hus, sought freedom for Bohemia from the Holy Roman Empire and Catholic rule. Smetana scores this poem with musical material from the Hussite hymn “Ye Who Are God’s Warriors.”

6. Blaník- The final piece of the work completed by Smetana in 1879. It is thematically linked to “Tábor.” Smetana wrote that “Blaník begins where the preceding composition ends,” Smetana continued. “Following their eventual defeat, the Hussite heroes took refuge in Blaník Mountain, where, in heavy slumber, they wait for the moment they will be called to the aid of their country.” No doubt, “Tábor” and “Blaník” make up the biggest nationalistic statement of the work. While previous movements describe the beauty of Bohemia and narrate its people and places, these two works glorify its past independence movement and signal hopes for a Czech independence that Smetana would not live to see.

A painting depicting the folk legend Šárka from The Maiden's War

A painting depicting the folk legend Šárka from The Maiden's War

Smetana suffered severe health problems at the end of his life which effected the composition of Má Vlast. Smetana began to lose his hearing in 1874 possibly due to the effects of untreated Syphilis. By 1875 he was almost completely deaf. This hampered his efforts to finish his tone poem epic but also hardened his resolve, possibly looking to the example of Beethoven before him to overcome his disability. He stopped composing altogether by 1882, having sustained mental deterioration related to his illness, dying in 1884 in a mental asylum. Má Vlast, which had been performed in individual sections upon completion, was finally performed as a complete work in 1882 with the deaf composer present. It was remarked that he could hear the music by his understanding of the score coupled with the movements of the performers on stage.

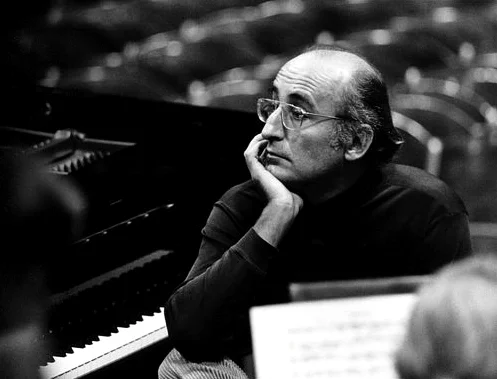

Rafael Kubelik (1914-1996) was one of, if not the preeminent conductor associated with the works of Smetana. Born in Bohemia, Kubelik undertook a steady rise as musician, graduating from the conservatory in Prague at age 19 in 1933. He gained a post as music director of the Brno Opera just three years before the Nazis shut it down in 1941, later gaining directorship of the Czech Philharmonic. He eventually fell out of favor with the German authorities and went into hiding in 1944 until the end of the war. He returned to conduct the orchestra in its first concerts after allied liberation, and founded the Prague Spring music festival. After the Soviet-backed coupe of 1948, Kubelik fled Czechoslovakia for the west, remarking: “I had lived through one form of bestial tyranny, Nazism, as a matter of principle I was not going to live through another.”

.jpg) Conductor Rafael Kubelik

Conductor Rafael Kubelik

In exile, Kubelik had a long career of music directorship posts that included the Chicago Symphony, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian Radio Symphony. In that career he championed and often recorded the works of Czech composers such as Dvorak, Janáček, and of course Smetana. Kubelik recorded Má Vlast more than any conductor of his era, leaving us with four excellent readings with the Chicacgo Symphony in 1953 (Mercury Living Presence MG 50013), Vienna Philharmonic in 1959 (SXL 2064), the Boston Symphony in 1971 (Deutsche Grammophon 2720 032), and finally at the Prague Spring Music Festival in 1990 reunited with the Czech Philharmonic (Supraphon – 11 1206-1 032). The latter recording is certainly an emotional reading for the conductor, who came out of retirement to lead concerts with the orchestra upon the fall of the iron curtain. That said, this reading presented here with Kubelik leading the Boston Symphony is usually considered the conductor's finest of the four, and regarded as the pinnacle of Má Vlast recordings.

Rafael Kubelik, conducting a public concert of Má Vlast in Prague, 1990

Rafael Kubelik, conducting a public concert of Má Vlast in Prague, 1990

My own experience with the piece is like that of many musicians and classical music fans, having encountered The Moldau a few times (I performed it once a number of years ago), but having little to no experience with the rest of the suite. My first real exposure to the complete work came when the Bamberg Symphony released its “direct-to-disc” version of the work three years ago, also recorded by Rainer Maillard and cut by Sidney Meyer. That 3LP set is tough to beat, the playing is superb and the sound is rich, enveloping, and three-dimensional the way only direct-to-disc can be.

However that recording didn’t make me fall in love with the work, as I really only ever revisited Vltava and Šárka, and found the other movements somewhat dull and lackluster. At the time I attributed that lack of enthusiasm for the piece itself, and it’s true that the latter movements of Má Vlast have never enjoyed universal acclaim the way Vltava/Moldau has in concert halls. However, Kubelik owns this piece for a reason, and his spirited reading with the excellent players of the BSO make a compelling case for Smetena’s work in it’s entirety.

Kubelik has not only a clear vision of the flow of this piece, but also an energy and vitality that propels the technical virtuosity of the Boston players to a blistering height. The opening theme is effervescent, the Vltava is flowing and churning, Šárka is earth shattering in its action, Bohemias Woods and Fields are rustic and pastorale, and even the often snore-inducing Tábor and Blaník have enough energy and momentum that I at least was intrigued while listening.

Make no mistake, if you want a complete version of Má Vlast, this is the one to buy, others may be good, but few will leave you with an appreciation for Smetana’s epic the way this performance will.

For this recording, I happen to own an original German box set pressing, and I remember why I never played it. It’s thin, harsh, and lacks any type of expansive orchestral image. Percussion is dull, strings are one-dimensional, and the cellos and double basses might as well be nonexistent. So much of this music requires pastorale “bloom”, and the original cut just doesn’t have it.

Fortunately here Maillard and Meyer have lifted a veil. In the opening phrases you can hear new space around the instruments, they now soar into the upper air of the concert hall, and everything is resonant, transparent, and finally full-bodied. This is the best example I have heard since the epic Abbado Rite of Spring, of the EBS team restoring a full-bodied sound to a formerly dull and thin production. It’s not just that EBS have improved the recording over the original product, but they have engineered it to be an audiophile experience in its own right, and this is one of the more enjoyable sonic outings I’ve had with the series so far.

My last review of these Original Source reissues certainly caused a bit of chatter, and I stand by what I wrote that the Brahms record was both cut too hot, and too close to the inner grove on one side. Fortunately here, while the record is cut with impeccable and powerful dynamics (some of the swells will surprise you, especially the end of Vltava), there was no harsh oversaturation to be had. Now, on the Bamberg box set I mentioned earlier, the EBS team cut that set onto 3 LPs with plenty of space available for each movement. That was of course a direct-to-disc cutting, so the team may not have been able to fit it on 2LPs if they tried, but the shift to 2LPs for this release was noticeable only on side 2 which contains the two best movements in the work; Vltava and Šárka. This means Šárka gets squeezed onto the inner grove of side 2, and those of you that buy the record will once again see for yourselves; it’s tight.

I had on hand for review, a very serious turntable, the Reed Muse 1C idler wheel drive table fitted with the 5T laser-guided, tangential tracking tonearm, and an Air Tight PC-1 Coda cartridge, all set up professionally by Axiss Audio. I mention this because the laser system on this table uses a light to alert the listener whether the tonearm is in tangential alignment. The finale of Šárka was cut so close to the label of side 2, that the Reed 5T was unable to follow it that far, and the green light turned into a red flashing light to alert me that the cartridge was tracking beyond what the tangential motor at the base of the tonearm was capable of following.

The Reed 1C turntable and 5T tonearm

Did this result in a little bit of audible “crunch” in the final 30 seconds of that movement? Yes.

Was it as bad as the infamous Brahms cut? No, thankfully.

What does this mean? Well it means I would prefer it if EBS didn’t cut so close to the inner groove, I think most audiophiles buying expensive AAA cuttings of classical music would not mind paying for an extra LP to prevent these issues (some may not find it to be an issue, but I’m speaking from my own preference).

Even with that minor gripe, I feel compelled to highly recommend the OSS edition of Má Vlast. Finally, at last what is arguably the best commercial recording of Smetana’s magnum opus is given an engaging, dynamic, and rich presentation hitherto unavailable to the vinyl listening public.

Music: 11/11

Sound: 10/11

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart- Piano Concertos No. 25 and 27

Friedrich Gulda with the Vienna Philharmonic conducted by Claudio Abbado

Production and Recording Supervision: Rainer Brock

Recording Engineer: Volker Martin

Recorded in Boston Symphony Hall, May 1975

Reissue mixed by Rainer Maillard & cut by Sidney C. Meyer directly from the original analogue source at Emil Berliner Studios

180g Pressed at Optimal

Limited Edition of 3350

I will admit to not being a Mozartian. Now, I’m not saying I don’t marvel at the beauty of Mozart’s compositions, his melodies, his harmony, his mastery of form, but there are people who truly understand Mozart at a theoretical level. I’m not one of those people, because those people are most often pianists, those who have the most exposure to playing Mozart at his most brilliant. What do I mean? Well, the composer spoiled us with two compositional forms, his sublime operas, but also his piano concertos, which in my opinion, express his qualities better than any other of his orchestral or chamber works.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) hardly needs much introduction. He is one of the most ubiquitous names in music, even among people that have never heard more than 30 seconds of his work. He accomplished more in his short 35 years on this earth than most accomplish in multiple generations. Among his symphonies, operas, concertos, solo sonatas, and serenades, the composer left us with 27 numbered piano concertos (four of which were arrangements of other composers work, a very normal practice in those days). The latter concertos are mostly goldmines of the composers mature style, and the two here shining examples of that.

W.A. Mozart

W.A. Mozart

The Piano Concerto No. 25 in C KV 503 was completed at the end of 1786, and it was the last of a dozen piano concertos the composer penned in just two years time. The C Major concerto is both optimistic, and grand in scale, with its opening movement marked “Allegro Maestoso” and an instrumental scoring that includes both trumpets and timpani. Despite the large scale of the concerto, there is a subtle intimacy to the voice leading, and tradeoff between soloist and orchestra, that is hallmark of Mozart’s mature style. Beethoven’s own C Major Piano Concerto was written just 9 years later, and it’s hard to imagine he wasn’t influenced in his tonal and musical choices just a little bit by KV 503, as Beethoven’s early style can be described as “Mozartian” just as much as Mozart’s late style can be described as “proto-Beethovian,” a term I am most certainly making up.

When Mozart completed his final piano concerto, No. 27 in B Major in January of 1789, he was in dire straits. Family illness, financial woes, and waning popularity conspired against him. He fell ill in the fall while premiering two of his finest operas, La clemenza di Tito and The Magic Flute, and by December he was dead. The last work Mozart performed in public, the B Major concerto is one of contemplative serenity. Some biographers and musicologists like to attribute grim, if not fateful foreboding to this work such as they do to Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, but those theories, like many found in chain emails from elderly relatives we only see at holidays, are hindsight-driven conspiracies.

In reality, B Major concerto is an elegant refinement of techniques the composer had been building over the last 5 years. Mozart’s melodic beauty, as well as his comic wit, are present just as always. What’s new is the thematic development and harmonic playfulness (hinting of minor keys) looking towards new possibilities, ones that would be further explored by other Viennese composers in the continuing years.

These performances by Friedrich Gulda and Claudio Abbado have been fan favorites for decades, although I lack the Mozart credentials to say if they are “definitive”. Friedrich Gulda (1930-2000) was an iconoclastic pianist that both thrilled and polarized audiences for much of the later 20th century. He was not just a performer and composer in classical, but also in jazz, as well as an influential pedagogue, teaching piano great Martha Argerich, as well as his teammate on this outing: Claudio Abbado himself. Gulda may be considered controversial in his musical choices, as well as his fashion aesthetic (I once read a review where he was said to be dressed like a “Serbian Pimp”), but few would argue that he is primarily known for his Mozart interpretations. He even published his own Cadenza for KV 503 that is still performed today.

Friedrich Gulda at the piano

Friedrich Gulda at the piano

Mozart’s concertos need a strong voice, and Gulda provides it here, accompanied by the supreme Mozartian orchestra and his old friend Claudio Abbado. Abbado and Gulda make an excellent and efficient team, their styles complementing each other well. Gulda plays with impassioned bravado, but also an intense sentimentality, this leads to some chilling moments in the C Major concerto where the piano takes over the orchestral line, or in the B Major when he uses the countermelody to reinforce the leading strings. Gulda imbues these performances with character, and that’s what any performance of Mozart demands, otherwise you’re left with simply a very pretty sonata-form.

I don’t have an original of this recording to compare, but the sound on this Vienna-recorded disc is very pleasant, with a nice string tone compared to what I’m used to with DG productions. There is a nice “hall ambience” that isn’t always there on the Berlin discs that comes out in this Vienna setting. Gulda’s piano likewise has nice decay and reverberation in the subtle moments, but lacks a bit of depth and bottom end weight when compared to the orchestra. There is incredible dynamic range from the orchestra, but both macro and micro dynamics on Gulda’s piano left me wanting, which may be due to the mic setup. This is a very tonally “pretty” recording, but don’t expect Mercury Living Presence-levels of piano imaging.

There is a relative lack of quality audiophile Mozart recordings in the vinyl-verse, something perhaps attributable to their lack of popularity in the Mercury and RCA catalogues that are the bread and butter of audiophile collections. So, for that reason, I’m thrilled that EBS has chosen this title for reissue, and am crossing my fingers for more reissues of Mozart/Beethoven/Haydn small-scale orchestral, concerto, and chamber recordings, of which DG has a huge catalogue.

If your main familiarity with Mozart is his Jupiter Symphony, Magic Flute Opera, or the dreaded Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, I can highly recommend this tuneful and passionate rendition of his later piano concertos, with the beautiful sonorities of Mozart’s hometown orchestra playing at the top of their game. An essential bit of repertoire for any classical library, and another example of how EBS with this series can add richness to a period of recordings often dismissed by myself and others.

Music: 10/11

Sound: 9/11