Karajan, Bruckner, and the Next Generation of Deutsche Grammophon’s Original Source Series - Part 3: “The Force Awakens” - Unleashing Bruckner In a Listening Room Near You

A Deep Dive into the History and Technology behind this Epic AAA Reissue, mastered and cut directly from the 8-track master tapes

OK, I couldn’t resist. Following on my previous appropriations of movie and TV titles for this series of articles (pace the one obligatory nod to good ol’ Bill S.), this movie ref. just seemed like the bomb.

Karajan and the BPO playing Bruckner at full tilt in Original Source Technicolor Widescreen 3-D?

“The Force Awakens” indeed!

(And considerably better than JJ’s derivative rehash… send your emails to our esteemed editor, please.)

Getting serious for a moment…

I have a confession.

When I knew I was going to be reviewing this new set, hard on the heels of the Giulini Bruckner vinyl reissue, I was a little - shall we say - hesitant about having to immerse myself so fully in all nine Bruckner symphonies over such a short, concentrated period of time. Even if I expected these records to sound every bit as good as indeed they do.

It’s a lot of music, and music of a particular style and intensity that doesn’t easily lend itself to extended, concentrated listening in large and long doses. These are serious “event” works, each symphony best digested at a single sitting with plenty of breathing room around it.

As in days or weeks of breathing-room.

To listen to all nine of these substantial works in a relatively short space of time would be a little bit like eating a fabulous steak (or roast beef) dinner with potatoes au gratin and roasted vegetables, followed by chocolate cake mit schlagsahne every day for several weeks - very rich, and a little indigestible.

The Bruckner oeuvre, while often equated with that other titanic orchestral cycle of the late Romantic era - the Mahler symphonies - is actually a very different beast. Each of the Bruckner symphonies lives much in the same world in terms of form, style, and sound as the others (kind of an oversimplification, I know, but also kind of true). Even the earlier works point towards Bruckner’s maturer utterances (not entirely surprising: remember that the first numbered symphony was completed when the composer was in his 40s - this is no product of his juvenilia).

By contrast, each of Mahler’s symphonies occupies its own world, albeit clearly contained within the same Mahlerian universe. The “Death to Resurrection” journey of the Second is worlds away from the bucolic pleasures of the Fourth (even accounting for the shadows that creep across the slow movement) - to give but one example. The Bruckner cycle has always felt more like one long, unified journey, with its nine separate chapters, moving inexorably towards the almost abstract transcendence of the 9th’s final Adagio - Anton’s own symphonic Ring cycle, perhaps? That “sameness” to the music means that listening to too much Bruckner in one go - even an extended one - can be a bit of a slog.

Also - again, in all honesty - I am more likely to reach for a Mahler symphony than a Bruckner one when I’m in the mood for The Big Romantic Statement. I appreciate the variety of Gustav. And I have always connected deeply with Mahler’s idiom since I first caught Lenny conducting the “Resurrection” Symphony live on TV from Ely Cathedral when I was 13. A revelatory experience that changed my musical horizons. It’s all simply a matter of personal preference.

So I was most pleasantly surprised when one of the gifts this set bestowed upon me was the ability to hear Bruckner in a different way, a lighter way. This may sound surprising, since one thing Karajan, the Berlin Phil, and Bruckner are not renowned for is their lightness! But there it was. I was finding the music more digestible, and certainly more multi-hued, than I had before. And Karajan keeps things moving along at a decent pace - unlike many who too easily start to wallow.

I suspect a lot of this lightness is down to the vastly improved Original Source sonics. Yes, you are getting the monolothic power when need be, but within those mountain peaks you feel freer to join the musicians as they wander through the Alpine lowlands, gazing on spring flowers and mountain lakes. (Too much pastoral? Well, that’s how it felt to this listener).

One of the recurrent joys I found in these records was catching on the wind the distant strains of medieval-like chant and polyphony, spun out by a small choir of solo winds and brass, supported by a bed of murmuring strings. I had such a sense of the composer channelling his love of all the church music he must have listened to and performed throughout his life. I have never heard this aspect of his music so evocatively delivered as on these recordings. (Hats off to the matchless wind and brass of the BPO during this period, including James Galway on principal flute).

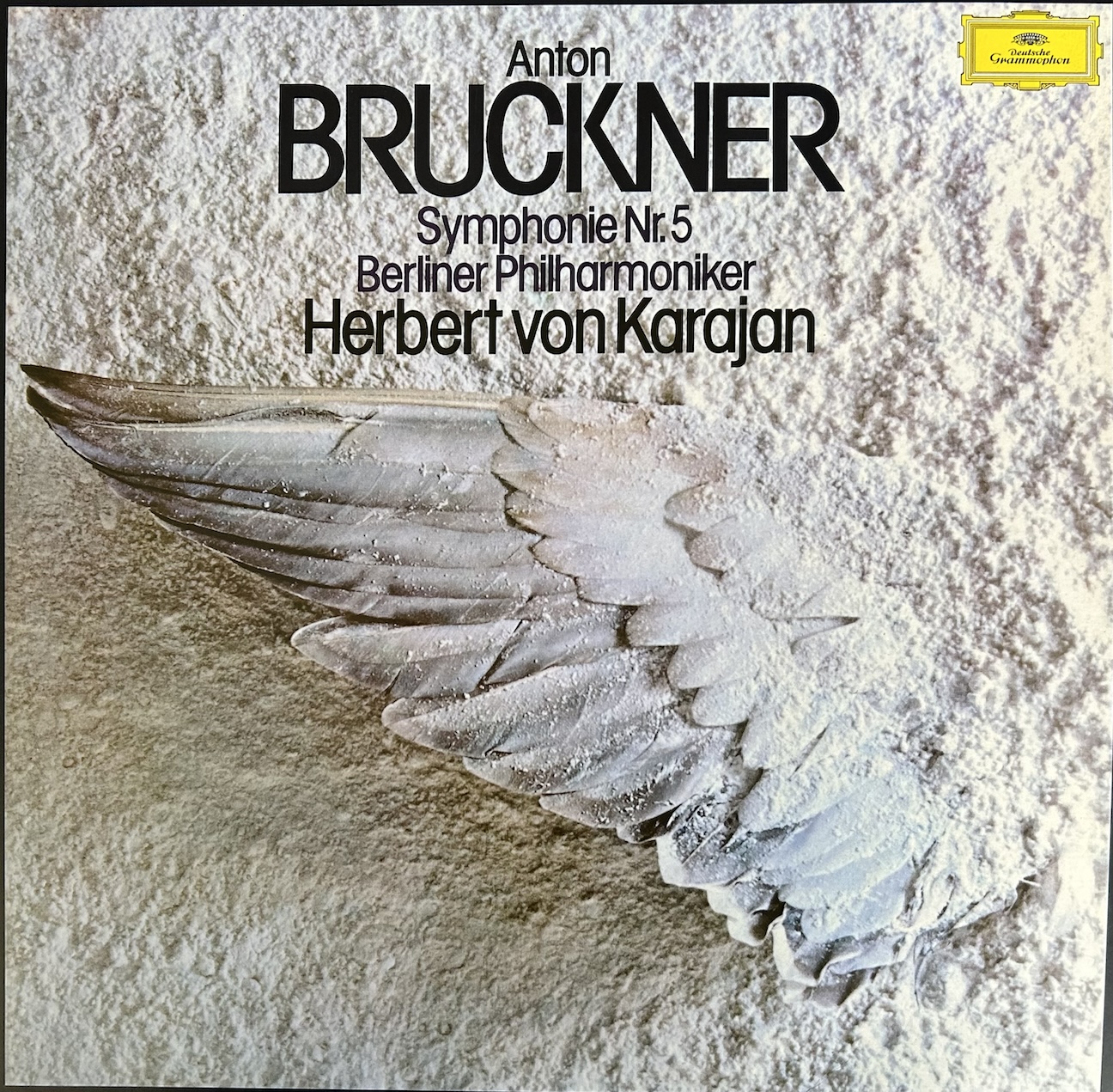

If you want a real taste of this cycle at its musical and sonic best, put on the slow movement of the 5th (this recording features probably the most vivid sound of the entire set - it’s pretty awesome, frankly). Those opening heavy pizzicato string steps hint at either: 1/ the measured tread of a pilgrim wandering in the mountains; or 2/ the presence of a vast, powerful beast that can unfurl at any moment - think the dragon Smaug coiled around his gold in the Lonely Mountain, ready to lay waste to any would-be burglars in The Hobbit.

It’s probably a bit of both.

(That sense of the enormous coiled power of the BPO held in check, but ready to let loose at any moment, is a lurking presence throughout this set, and it’s pretty thrilling).

As the movement progresses, a haunting oboe melody unfurls, redolent both of the cloister and of a serenading lover, joined by other wind and undulating strings. A pause. Then the strings enter en masse, chorale-like, and we move into a realm that seems to aspire heavenwards even as it still feels rooted in the beauties of Nature and Life itself. Bruckner’s polyphony is here, as elsewhere, reminiscent of ancient times even as its typically unexpected harmonic shifts are thoroughly modern. The slow, inevitable build to a series of massive, brass-dominated climaxes accommodates a series of digressions along the way, even returning occasionally to those opening pizzicato footfalls. Chromatic phrases in the winds build tension, then give way to near silence. Karajan controls all of this masterfully, and the sound ranges effortlessly from capturing all the tiniest nuances in close-ups that don’t sound highlighted, to expanding into ultra-widescreen “epic” without catching breath.

After listening to this movement several times over many weeks I found myself thinking this may be some of the most beautiful music ever written - or recorded. All of life’s fear and pain, joy and love, and aspiration towards something transcendent (whatever that may be for each listener) felt contained within those 21 minutes, communicated so naturally and effortlessly that my room and the paraphernalia of my stereo simply disappeared. Remarkable.

You might find this happening a lot as you listen to this set.

But there is another point to be made here.

Comparisons may be odious, but I will make the observation that the beauty of this movement as conveyed by these performances was of a different order than the beauty to be found in, say, Mahler’s Adagietto from the 5th Symphony - often described as some of the most beautiful music ever written. Poignant, full of yearning and heartbreak, sublime in its sense of some level of equanimity at the close… it’s certainly one of Mahler’s most remarkable inventions, with those harp arpeggios adding their pointillistic brush strokes to the keening emotion of the strings.

And yet. And yet… The Bruckner felt more profound, more full of secrets yet to be disclosed; less obvious in its beauty. More suffused with some great truth only the music could speak of.

I know which one I’d take to my desert island.

And that’s coming from a devout Mahlerian.

Maybe I’ve underestimated Bruckner - a thought I would have many times as I listened to this set.

And especially in relation to the three early symphonies.

KARAJAN AND BRUCKNER GO DIGITAL

Leaving aside the known quantities of the major symphonies (which I will come to later), I found myself most delightfully surprised by listening for the first time to these recordings of the three earlier symphonies, 1-3, all recorded digitally.

Well, when I say, “listening for the first time”, I’m not being strictly accurate. I still have all those original LPs from when they were first released in the early 1980s, but I think I only listened to them once back in the day because the sound was so unremittingly awful. Early digital at its worst combined with ridiculously long sides to create a sonic earsore. (Yup, I made up that word, but that’s exactly what those records were: earsores).

I imagine that when DG and EBS were contemplating the possible release of this set there was some discussion as to whether to include these digitally recorded symphonies at all. But it would have somehow been wrong to release only the truncated cycle, and, as it turns out, Maillard has been able to substantially refurbish the sound to a degree that I never thought possible (an improvement that eluded previous digital remasterings).

In Maillard’s extensive essay in the set’s booklet, he goes into some detail as to how this was achieved:

“Herbert von Karajan supported the introduction of digital technology more than anyone else. He recognized the opportunities presented by the new technology earlier than most, in terms of both sound quality and marketing. It is therefore no wonder that DG's first digital productions were made with Herbert von Karajan as early as 1979. The Bruckner Symphonies 1-3 produced in 1980 have only ever existed as digital recordings in the DG archive.

“Karajan felt that under no circumstances should the introduction of the new technology lead to any compromises in the usual workflow. He and his team were determined to stick to multitrack technology, because it was the only way to make three-dimensional mixes possible in the future. The possibility of releasing quadraphonic recordings into the home audio market was never off the table; today Dolby Atmos surround mixes of both new and old recordings are being done more and more.

“Karajan and his team were reluctant to record without retaining the possibility of being able to make subsequent balance changes. This is why Karajan - in contrast to other artists transitioning to early digital - stuck with multitrack technology. This was a problem, because at that time making edits on the digital tapes was significantly more complicated than with analogue tape. Initially, there was only one digital multitrack recorder that allowed for “copy-paste” music editing: the 3M recorder.

"Today, we recognize that early digital recordings struggled to achieve the sound quality of their analogue predecessors. At the time, however, these deficiencies were either not heard or not taken seriously, because the music industry's great digital promise was that its products would be absolutely free of noises and artifacts. Ironically, given Karajan’s dedication to achieving the best sound quality possible, and his belief in the sonic advantages of the new digital technology, the problems and difficulties exhibited by digital in its early days are especially evident in his recordings of this period.

“One of the main reasons for this lay in the digital 3M multitrack recorders used primarily by Karajan. Their converter technology was anything but fully developed and trouble-free. But Karajan had to have digital multitrack productions right from the start, and he and his team became caught up in the idea of progress to the exclusion of everything else. Even though they could have used a Sony PCM 1600, which was a much better-sounding recorder than the 3M, it could only accommodate 2 tracks. For Karajan, abandoning multitrack technology and going back to stereophonic, 2-track recording of any kind - be it analogue or digital - was not, and could never be, an option.

“As a result, Symphonies 1-3, produced with the supposedly superior digital technology, lag behind the earlier all-analogue recordings sonically, because digital artifacts, when they occur, are perceived as more disturbing than analogue artifacts.

“Today - with the many advances in digital technology - it is now possible to achieve some sonic improvements in these recordings. There was, of course, the question of whether we should be including any recordings made digitally within the Original Source Series. These vinyl reissues, after all, have hitherto been purely an all-analogue product. But, given we are celebrating Bruckner’s 200th Anniversary year, and the significance of Karajan’s recordings within the history of the composer on record, we felt it was more important to present Karajan’s Bruckner cycle complete. (Also, these early symphonies were still primarily intended for release on LP, as the introduction of the CD was still in the future).

(Photo:EBS)

Maillard:

“With the digital multitrack tapes, the task before us was to find an ideal workflow for improving the sound quality for this re-release. Several issues came into play here.

“The sound quality of the analogue-to-digital-to-analogue conversion in particular was a shortcoming of the old 3M machines. In fact, in the 1990s DG started to equip its 3M machines with digital interfaces in order to be able to carry out the digital-to-analogue conversion with newer and better converters. However, the 3M machine at the time of Karajan’s digital Bruckner recordings - a decade earlier - worked with a sampling rate of 50 kHz, which is no longer used today. For the present release, the tapes were transferred to a workstation and upsampled to 96 kHz. Most of the digital artifacts from the AD conversion were then removed using new digital tools. Here, digital technology definitely offers advantages over a purely analogue workflow (although removing digital artifacts is not even necessary with analogue multitrack tapes). After doing this we found the sound had already been greatly improved, but it still had an unpleasant quality to it. This was due to the primitive analogue-to-digital conversion of the 3M machines.

“In order to further ameliorate the harsh sound of the original analogue-to-digital conversion, Emil Berliner Studios took the unusual approach of deliberately using a tube-based mixing console from 1960. (Incidentally, this was the same console which Herbert von Karajan and his production team used to produce his legendary Beethoven symphony cycle in the early 1960s).

ebs.jpg) Tube based mixer from 1960, used to record Karajan's 1962/63 Beethoven Symphony cycle, and pressed into service for the remixing of his digital Bruckner recordings (Photo: EBS)

Tube based mixer from 1960, used to record Karajan's 1962/63 Beethoven Symphony cycle, and pressed into service for the remixing of his digital Bruckner recordings (Photo: EBS)

"The summing on this console is passive. This functional principle, which guarantees a particularly clear sound, was also the model for the modern passive mixing consoles we designed specifically for the OSS project. However, unlike our current consoles, that 1960 vintage mixing console had a tube stage at both the input and output stages. These were driven relatively "hot", which leads to unavoidable overtones. And it is precisely this effect - actually known as the distortion factor - that is often referred to as the "tube sound”, and it behaves differently with tubes than with transistors.

“We also deliberately used passive filters constructed according to this principle in tube technology. These filters likewise "color" the sound of the mix, adding an "analogue" quality. This was all done with the aim of caressing the ear with "analogue colorations”, thus providing a counterbalance to the digital artifacts that might otherwise give a certain cold, harsh quality to the sound.

“Herbert von Karajan's sound engineer, Günter Hermanns, originally added a slight amount of reverberation to the recordings by using a very early digital reverberation system. This was necessary because, with the digital recordings, he hadn’t used room microphones to capture ambient sound (something he had done with his earlier analogue recordings). To replicate this reverb today we used a much better sounding, purely analogue echo chamber that produces a very balanced and pleasant reverb.

“The initial euphoria of digital technology led to another anomaly in the Karajan recordings, which was not even noticed at the time. Different recorders used at different stages of the production process actually played back the digital tapes at slightly different speeds. This affected not only the speed but also the pitch of the recordings. During the late 1970s, Karajan had the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra tuned to a very high concert pitch of up to 446 Hz. This helped him achieve a more brilliant sound. In fact, some of the original releases of his digital recordings are even higher in pitch. This speed discrepancy has now been corrected, with the result that the playing times for the affected Bruckner symphonies have been slightly extended, and the timbre of the orchestra is now as originally intended.

“Unfortunately, when we came to work on Symphony No. 3, the multitrack master could not be found in the DG archive. We had to use the digital stereo mix-down from 1980 for this release. But, as with the recordings of Symphonies 1 and 2, we were at least able to correct the pitch, and process the digital tape via an analogue chain with tube equipment, thereby improving the sound.”

In an interesting addendum to the above, Maillard has recently revised his thinking concerning the “missing” master tape for the 3rd Symphony. It may not be “missing” at all!

Maillard:

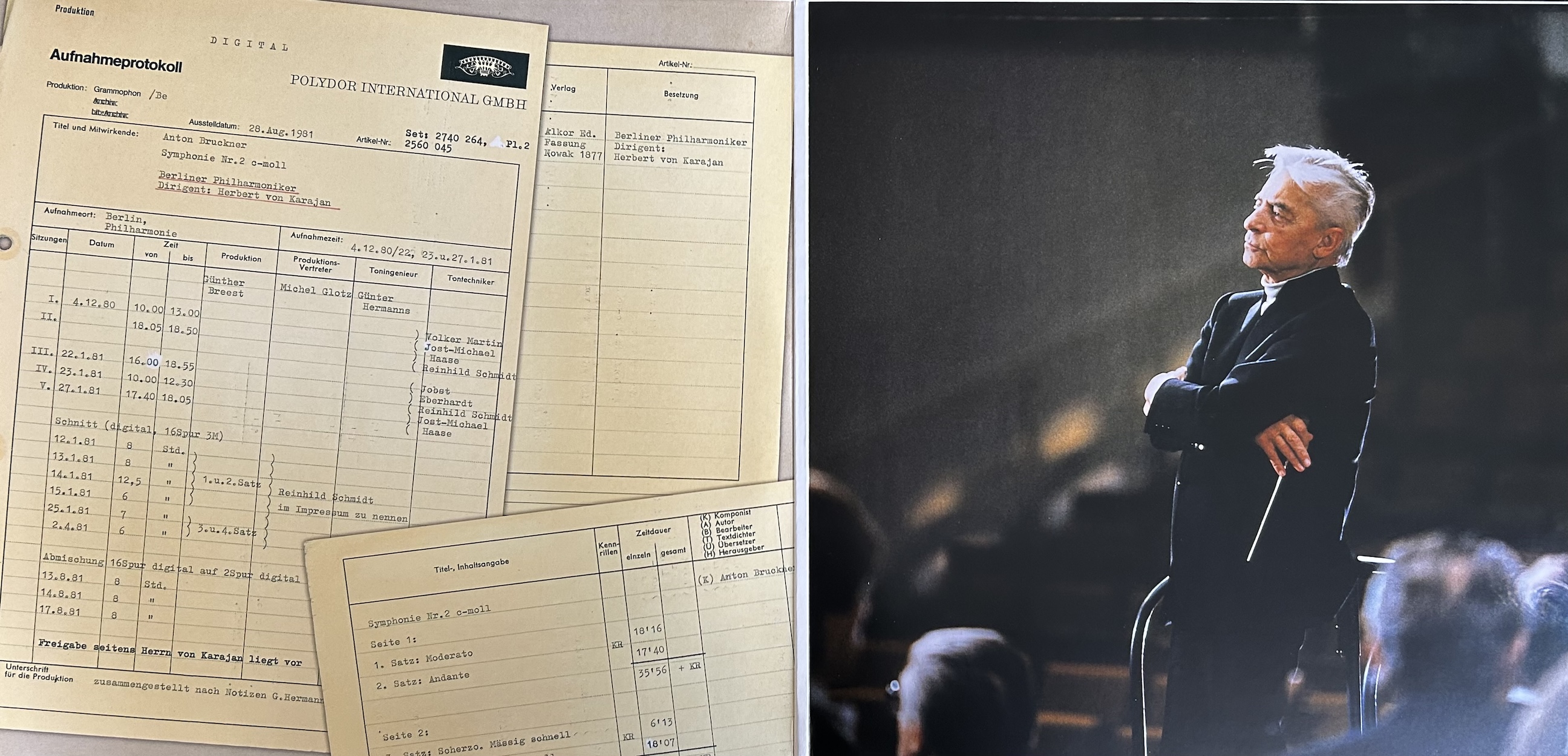

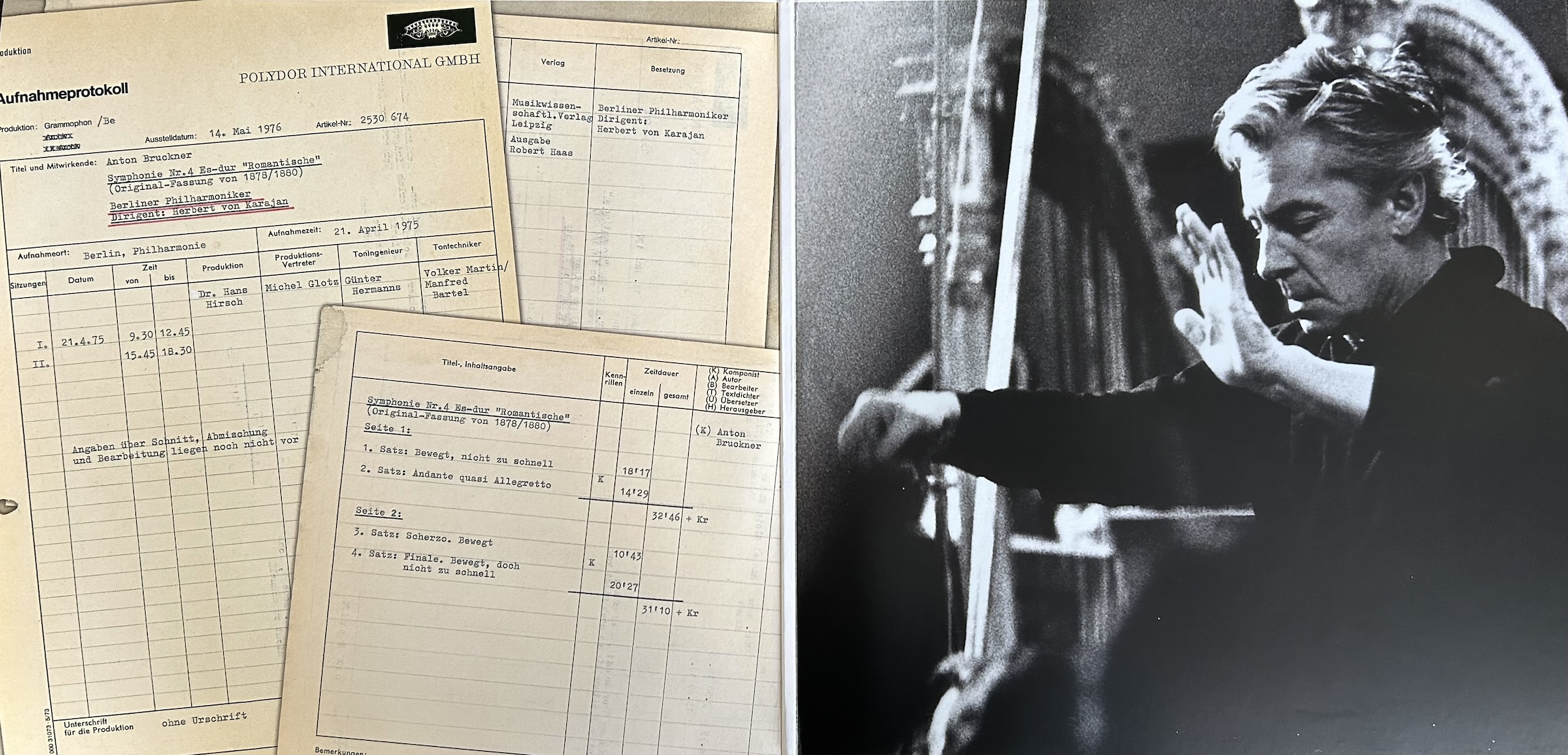

“In the gatefold photos of the sessions’ recording notes, you can clearly see the protocols.

“There is no multitrack editing mentioned (unlike with the symphony No 2). Only 2-track analogue editing is noted (with the same date as the sessions - I imagine Karajan wanted to hear a rough edit as soon as possible to see if he should re-record anything).

“Also there is the 2-track digital edited version, which was used as the master. No mixing from multi-track by Hermanns.

“I also remember that I heard fewer digital distortions on this symphony, so that might be a hint as well that this mix was actually done directly at the session to 2-track PCM 1600. In fact, like the old days before multi-track was possible.

“So this leaves us with two possibilities:

1/ This symphony was not recorded on multitrack (for some unknown reason).

2/ There were simultaneous 2-track and multitrack recordings and for whatever reason they decided to use only the 2-track in postproduction. In that case there was never a Multitrack Original created - ever. (This happened sometimes with HvK productions, but normally DG then archived the unedited takes instead of the master… That way a new edit could be done later. In this case, the original takes could not to be found anymore.)”

If you start your listening to this set with these early symphonies you will find the sound more than acceptable. Largely gone is the abrasive digital edge of the original LPs (an edge preserved on the various CD etc. versions). Using that 60s tube mixing desk works wonders in mellowing out the sound, as does the carefully applied reverb from EBS’s stairwell. Whatever additional digital hocus-pocus was applied before going retro with that vintage mixing desk also clearly helped a lot. (How serendipitous that it was the same mixing desk used to record Karajan’s legendary 1962/3 Beethoven Symphony cycle. I wonder what other vintage technological goodies EBS has sitting in its storeroom).

It’s only when you switch to the AAA-sourced later symphonies that you will be immediately aware of all the analogue virtues missing from Symphonies 1 - 3: a more organic overall sound, with richer instrumental textures, and a more three-dimensional sonic space. Also, when it gets loud on the digital recordings there is more of an intimation of shrinking headroom, while on the AAA records there is a sense that the brass, for example, could expand infinitely and effortlessly until, essentially, you blow out your speakers!

Nevertheless, there are great pleasures to be had from Karajan and the BPO in these earlier works, and I really appreciated having the opportunity to get to know them better in such winning performances. Karajan treats them as seriously as he does the later works.

Symphony No. 1, with its overtones of late Schubert, particularly the “Great” C major Symphony, revealed itself to be of far greater substance than I had remembered. Karajan is unafraid to present the work in its earliest edition, minus the “corrections” Bruckner later imposed that robbed it of much of its iconoclastic character (something he did with many of his symphonies, egged on by pupils and colleagues who felt his music needed to “conform” more).

Up to this point in his career, the composer was most celebrated for his renowned playing skills as an organist, and his fine sacred music (masses and motets, the latter of which were my own notable introduction to his music when singing in my chapel choir aged 13 - gorgeous works which I urge you to investigate).

Given that, and the fact that his later symphonies are suffused with the spirit of the cloister, the 1st is unusual in that is more secular in spirit: cheeky, earthy, impassioned, yes, but also full of fun. Karajan gets all this in a winning traversal.

With the 2nd Symphony we are more recognizably moving into the Brucknerian idiom we’re all familiar with, from the very opening of the first movement, as the main theme emerges out of silence and then gently tremulandi strings. The slow movement, as so often with the performances in this set, is a standout, with Karajan keeping the inner pulse steady as a rock through the various meanderings. Again the contributions of the solo wind and brass are exquisite. The hushed conclusion with almost ghostly strings and interweaving wind is sublime. The Scherzo is full of Haydnesque humor and fun, lighter than the many Scherzos in later symphonies, and beautifully pointed by the Berliners. The Finale has a tremendous sense of motoric forward momentum, with repetitive figuration moving up and down the scale to build tension in a manner oddly prescient of the 20th century minimalists like Steve Reich and Philip Glass. The Berlin brass again cap off the whole enterprise in indomitable fashion.

I really fell hard for this symphony in this recording.

The 3rd Symphony speaks most forthrightly of Wagner’s influence, and indeed the older composer spoke highly of the first movement when solicited by Bruckner for his opinion. The work is dedicated to Wagner. It also attracted the attention of Mahler, who made a four-hand version of it for piano. The Trio section of the Scherzo (itself more overtly Brucknerian than its forbears in symphonies 1 and 2) feels like it could have been written by Mahler himself. Indeed the Finale anticipates Mahlerian juxtapositions of seemingly opposing musical material derived from real life occurrences. As Richard Osborne writes in his sleeve note:

These juxtapositions derive from Bruckner’s hearing dance band music from a hall opposite to where the coffin of a recently dead ecclesiastical architect lay. In Bruckner’s own description (recounted by his appointed biographer, August Göllerich): “Listen! Over there is dancing, whilst here the master lies in his coffin - that’s life. And that is what I try to show in my 3rd Symphony. The polka indicates the gaiety and joy of the world; the chorale recalls its sadness and pain.”

All of this contrast is vividly caught by the Berliners, with Karajan maintaining the sense of underlying form and structure, and keeping that forward momentum going to the final brass fanfares that end the symphony triumphantly: the rich panoply of life in all its many facets grandly celebrated.

Gatefold from Symphony No. 2. Herr Karajan does not look amused (Photo: DG/Lauterwasser)

Gatefold from Symphony No. 2. Herr Karajan does not look amused (Photo: DG/Lauterwasser)

SYMPHONIES 4 - 9 REVISITED

I imagine these are the symphonies listeners will be most familiar with, with the exception of No. 6.

The 4th was long the most popular of Bruckner’s symphonies, and there are many first-rate recordings of this in the catalogue. My personal favorite has long been Karl Böhm’s traversal with the Vienna Philharmonic in fine Decca sound. For those of you wanting to sample extreme Bruckner conducting, check out the expansive version by Sergiu Celibidache with the Munich Philharmonic on an EMI CD (which runs 78 minutes to Böhm’s 68 mins, and Karajan’s 64 mins). You will either “get” Celi’s approach, or wish for spontaneous combustion of yourself or your system somewhere in the middle of the first movement.

The Original Source Series has recently delivered us a firecracker of a 4th from Daniel Barenboim and the Chicago Symphony, which my colleague Michael Johnson welcomed with a rave review. It is indeed thrilling stuff, even if the brass seem a mite too untethered.

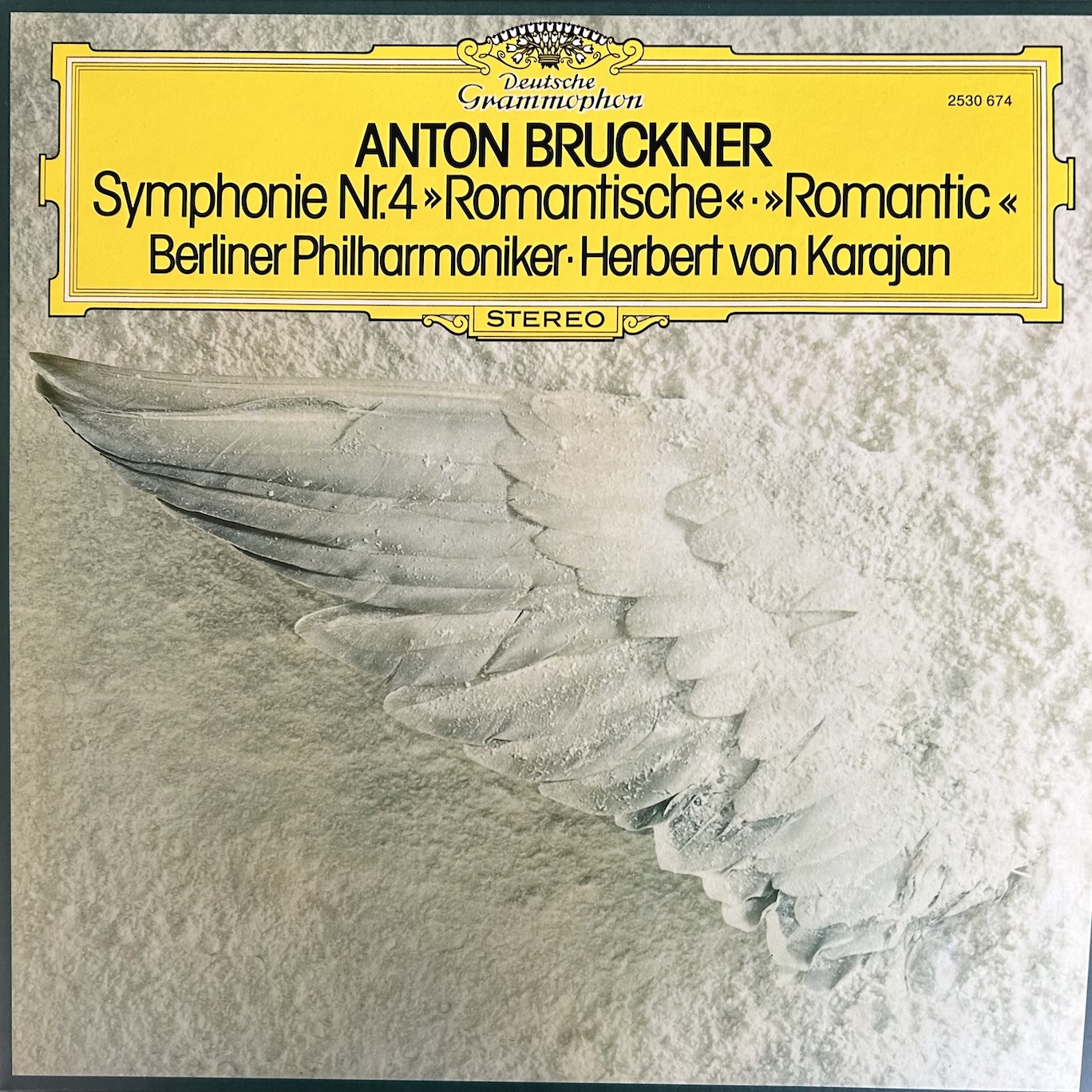

I must say that revisiting Karajan’s 4th left me a little wanting, in part because I felt the sonics were perhaps a little more diffuse than elsewhere in this set. This is the record to which the letter printed in the booklet refers, where DG insisted releasing this on a single LP back in the day, whereas Karajan favored a double LP set because of the long sides. He was overruled.

Now the symphony has plenty of room to breathe, and while it may not be a benchmark for me, it is still very fine.

Gatefold from Symphony No. 4 (Photo: DG/Lauterwasser)

Gatefold from Symphony No. 4 (Photo: DG/Lauterwasser)

This seems like the place to note that all the symphonies in this box are presented with one movement per LP side (with the exception of the 1st), and this gives cutting engineer Sidney C. Meyer full rein to do what she does best: deliver a cut packed to the brim with dynamics, headroom and rich tonal colors. It cannot be said enough: she is Rainer Maillard’s secret weapon in the Original Source enterprise. (And let’s also just mention here the outstanding work done by Thorsten Megow at Optimal on these dead silent, flat 180gram pressings).

I have already mentioned Karajan’s recording of the 5th, and it a real standout both sonically and musically. This is one of the trickiest of the symphonies to pull off, but here it emerges with full force as a major Brucknerian statement. It will never be my favorite actual symphony of the cycle, but this is the record to put on if you want to show off your system. Those string pizzicati which lead off several of the movements have so much weight, so much woodiness (from the instruments, the stage, and the hall), anchoring the massive orchestra waiting to unleash its full force. Which it does, over and over, to thrilling effect.

This is a very special recording, and maybe DG will release it separately down the road.

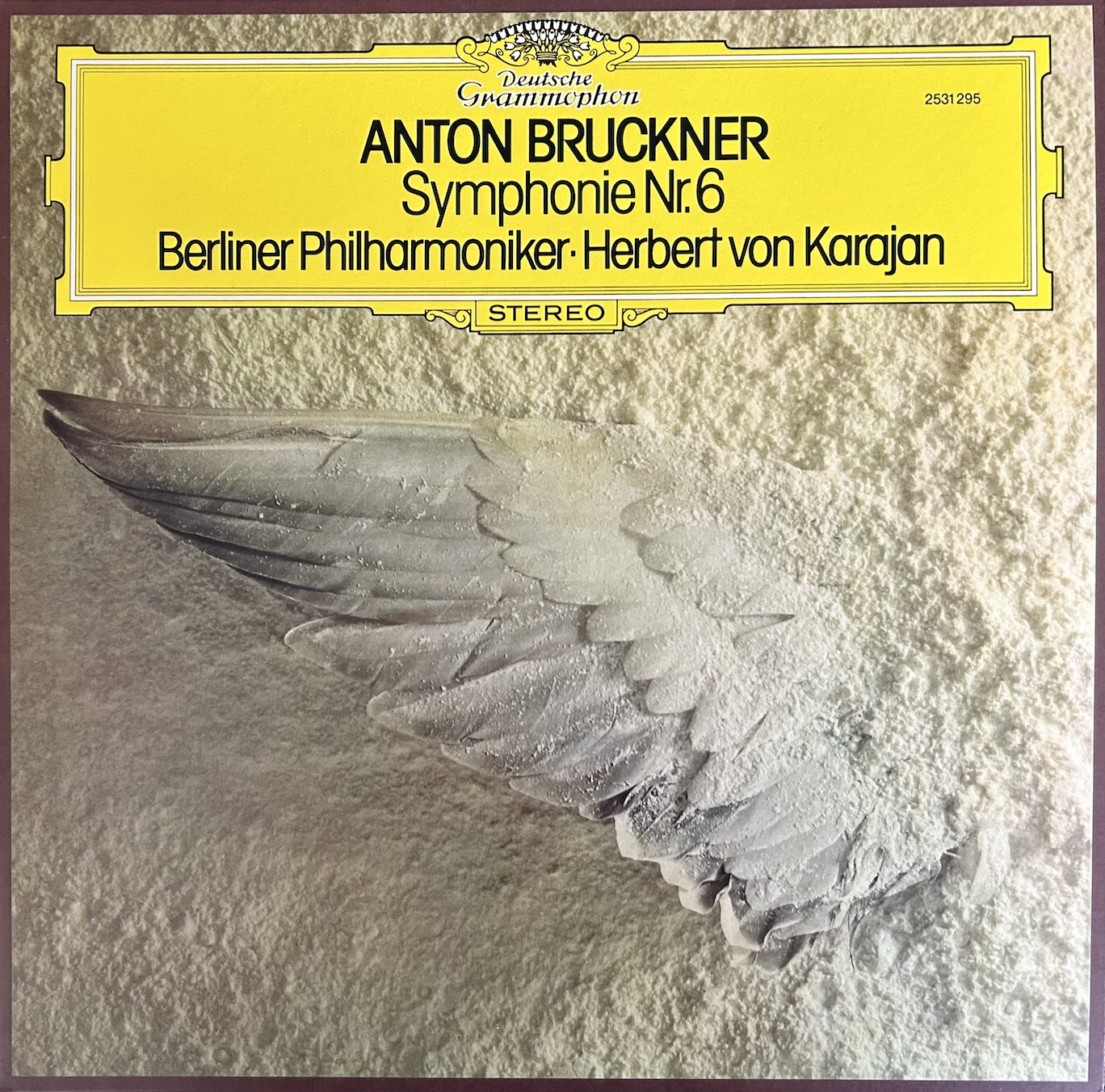

With the 6th we arrive at the one performance that might divide listeners - it’s a bit of a curate’s egg. In Osborne’s Karajan biography he speculates that maybe the Berliners were sight-reading this one. Yes, it really is that unfocused in places - and occasionally undisciplined. I’m not even sure they ever performed this piece in concert (online research yielded no information on this). Of course, the BPO’s sight reading is most other orchestra’s fully-rehearsed, but nevertheless this recording is neither conductor nor orchestra’s finest hour. I must confess that by the time I got to the first brass fanfares in the first movement I started to think I was listening to the score from some Hollywood action film from years gone by (Charlton Heston perhaps on a white stallion being cheered on by his troops as he liberates some city or other); it really had an element of self-parody about it. Not a good thing in Bruckner who tends towards the serious-minded, even when dancing is involved.

Look, this recording is fine, and some may appreciate that it is somewhat fleet of foot, but if you want to really hear this symphony done in a more overtly “Brucknerian” manner, as good a place to start as any would be Otto Klemperer’s granitic outing with the New Philharmonia recorded in Kingsway Hall in 1964. It just feels like Klemperer is more engaged with the work. I don’t have it on LP, but the remastering in the recent Klemperer CD box set is superb.

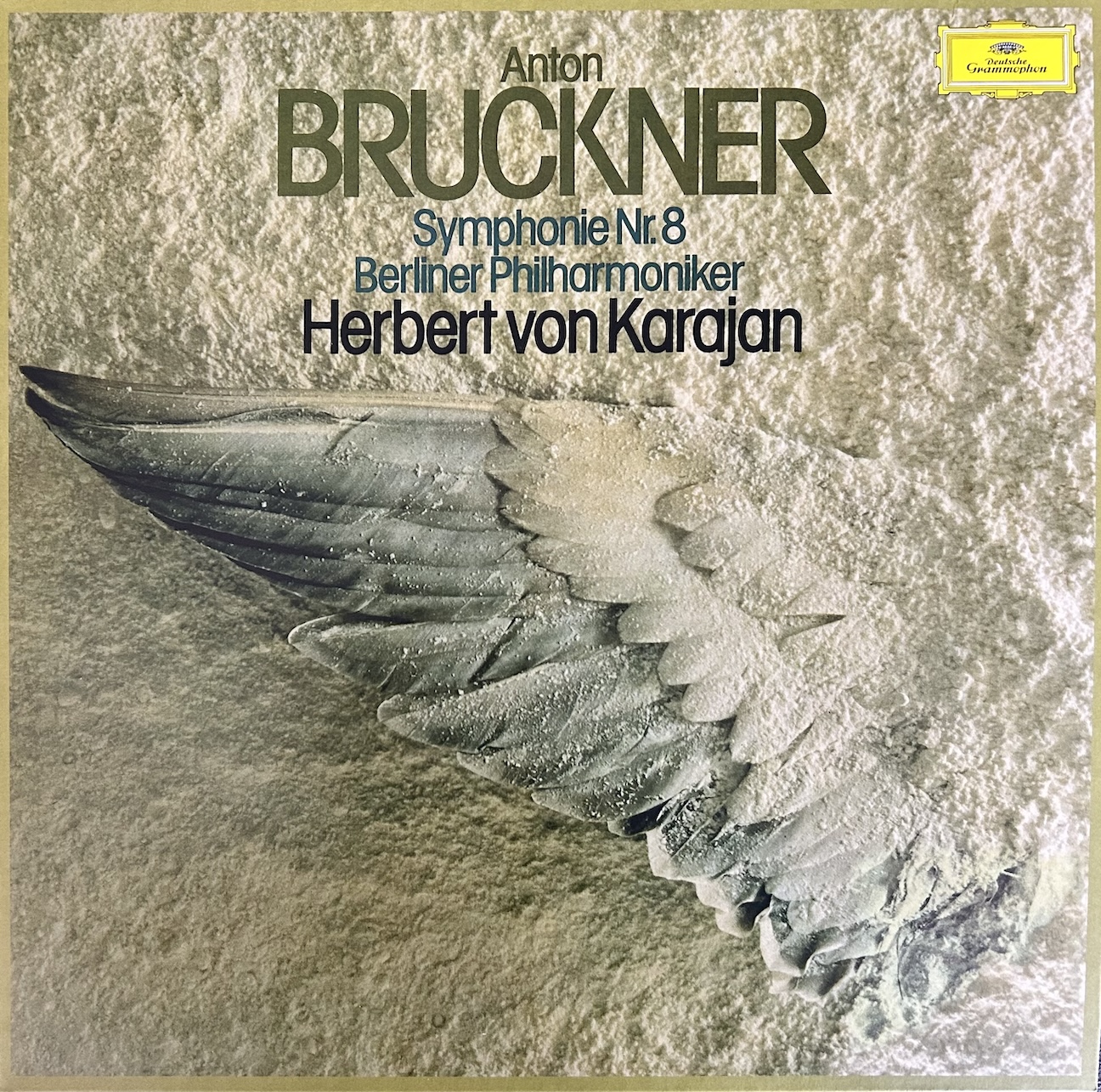

With the 7th and 8th symphonies we arrive at two of Karajan’s most authoritative utterances. Everything that makes him a great Bruckner conductor is on full display here: control of line and tempo (both on the micro and macro level), a sense of drama, a profound connection with the core of what makes Bruckner tick. And the Berlin Phil is on top form, effortlessly accommodating every demand of these monumental scores. I remember buying the 8th when it came out, not knowing the symphony at all, and being utterly spellbound. The slow movement is ravishing, with that harp intensifying the climaxes in a manner that will make you weep. The finale blazes with the Berlin Phil brass having a field day.

Likewise the 7th emerges in a single breath, from that opening ‘cello line that seems to meander but doesn’t, to the finale’s blazing apotheosis, Bruckner’s own version of Das Rheingold's Entry of the Gods into Valhalla.

It’s no accident that later recordings of both works with the Vienna Philharmonic, Karajan’s last, are rightly revered amongst Karajan and Bruckner enthusiasts, but these earlier BPO accounts do not suffer in comparison, especially in the stunningly upgraded Original Source sonics.

Two more that DG should consider releasing separately in the future.

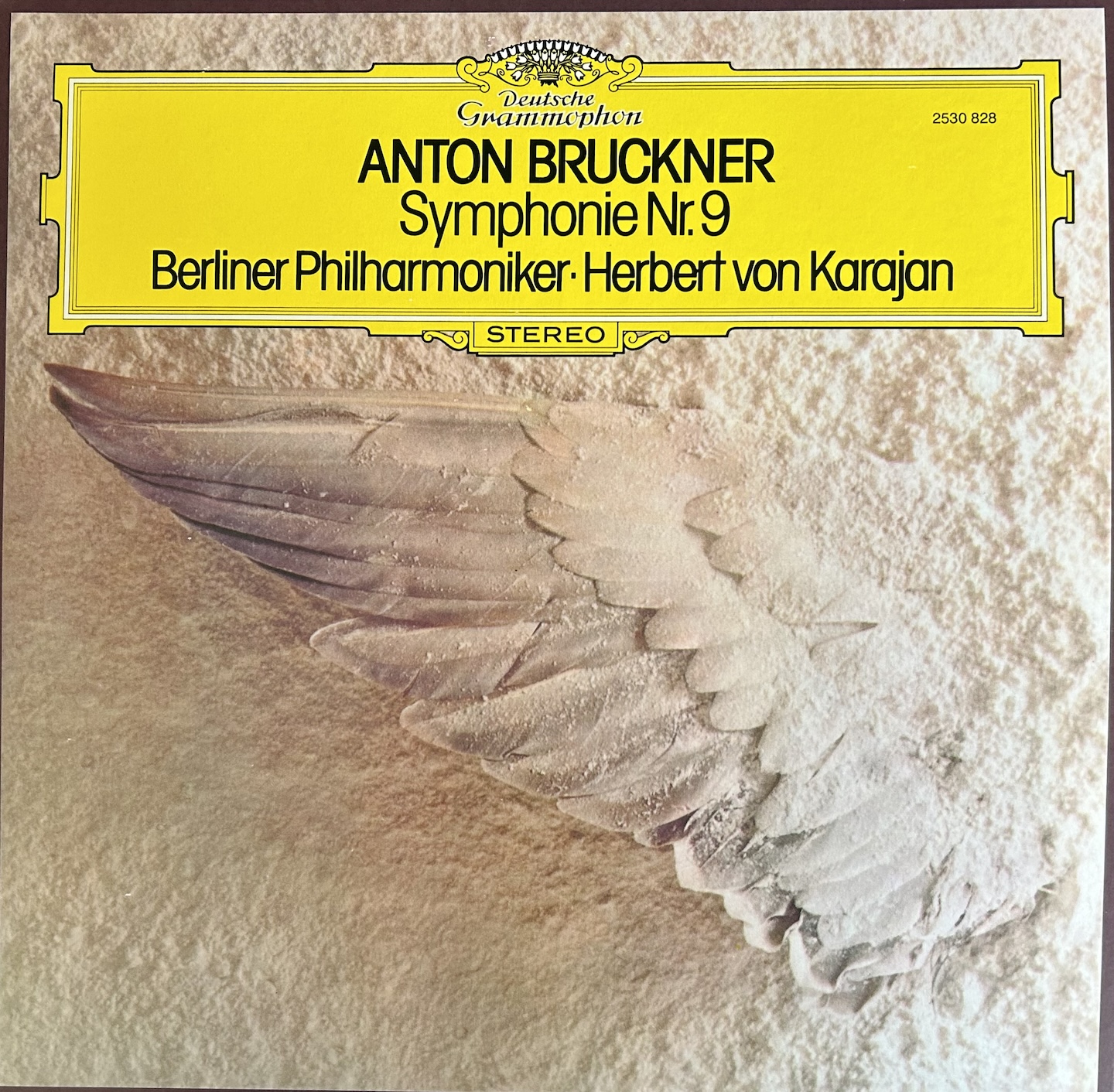

For me Karajan’s 9th doesn’t really kick in until the last movement, when it kicks in with a vengeance. From there on it is top-notch. There’s something a little unfocused about the first two movements, but then I am comparing this with my runaway fave in this work, Giulini and the VPO, recently remixed and remastered to perfection by the same EBS team. It’s very interesting to compare the recording quality of these two performances. The Giulini, although digital, is exceptionally fine, and I would agree with Rainer Maillard’s observation that it sounds closer to a Direct-to-Disc approach; whereas the Karajan in its latest incarnation has a slightly more distant perspective. You also get to directly compare the very different sounds of the two orchestras, with the VPO edging out the Berliners for sheer ripeness of tone, and deeper bass that really hits home, especially in the fantastic Scherzo (which might have you leaping around your listening-room)

Speaking of comparisons, if you own the Bernard Haitink/BPO D2D set of the 7th, recorded live by EBS at his farewell concert at the Philharmonie, you will be able to hear the Philharmonie “sound” in the raw, without the benefit (or otherwise) of the ambient channels and stairwell reverb present on the Karajan recording. It’s an interesting comparison. There’s no doubt that the purism of the D2D recording is compelling, but the Original Source remastering really enhances the so-called “Karajan sound”, giving the blend of the orchestra a helping hand. I would not want to be without either.

A quick note here. A few years ago DG Japan released two boxes of single-layer SACDs of the Karajan Bruckner Symphonies 4-9, remixed and remastered by EBS. I have one of these boxes, and the sonic upgrade over the original LPs and subsequent CDs was notable. It is also really nice to have Karajan and the BPO’s fine version of the Wagner Siegfried Idyll, originally coupled with the Bruckner 7th. But on this SACD set the added reverb is electronic, and you do notice the difference compared to what is on the new vinyl, which simply sounds more organic and, well, analogy all round..

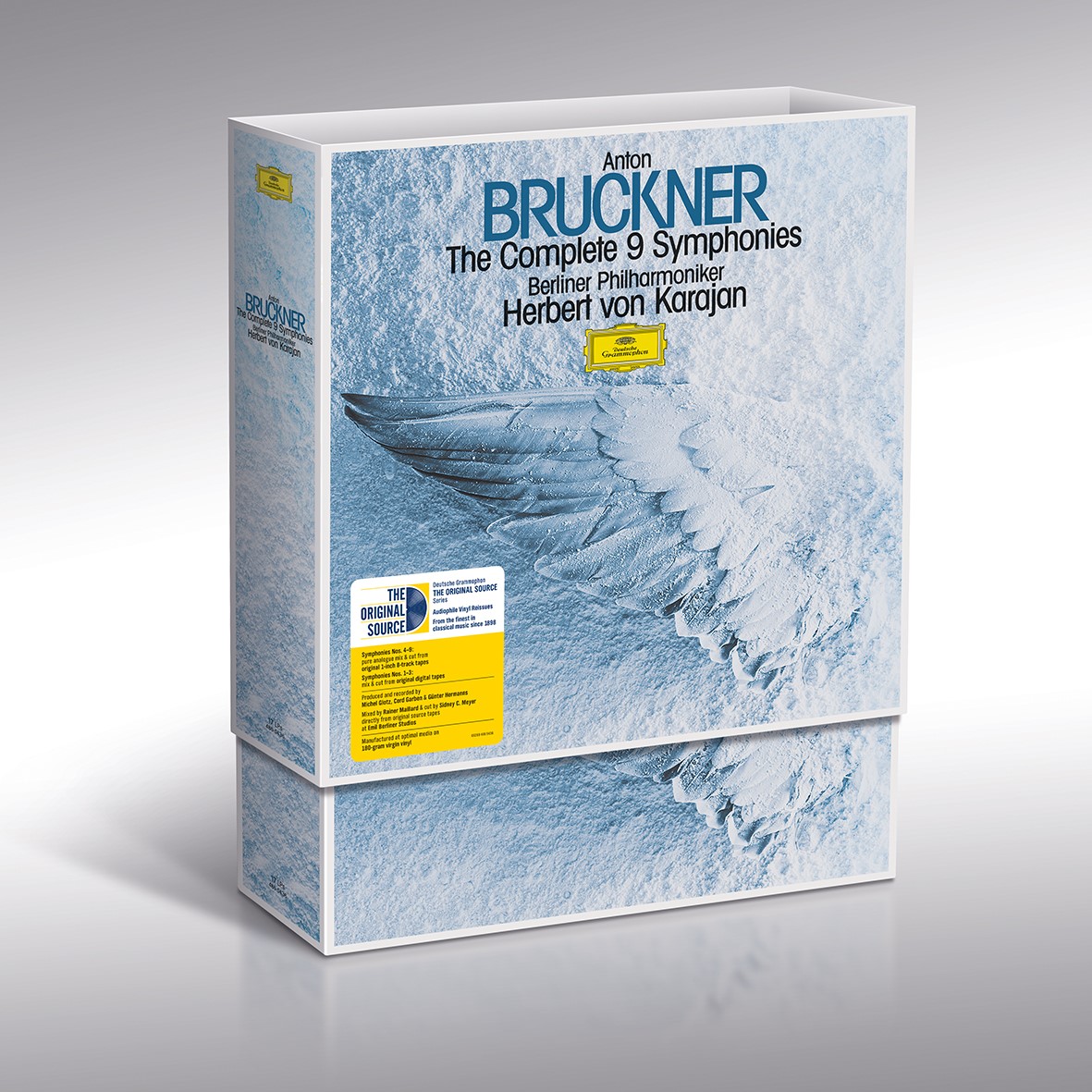

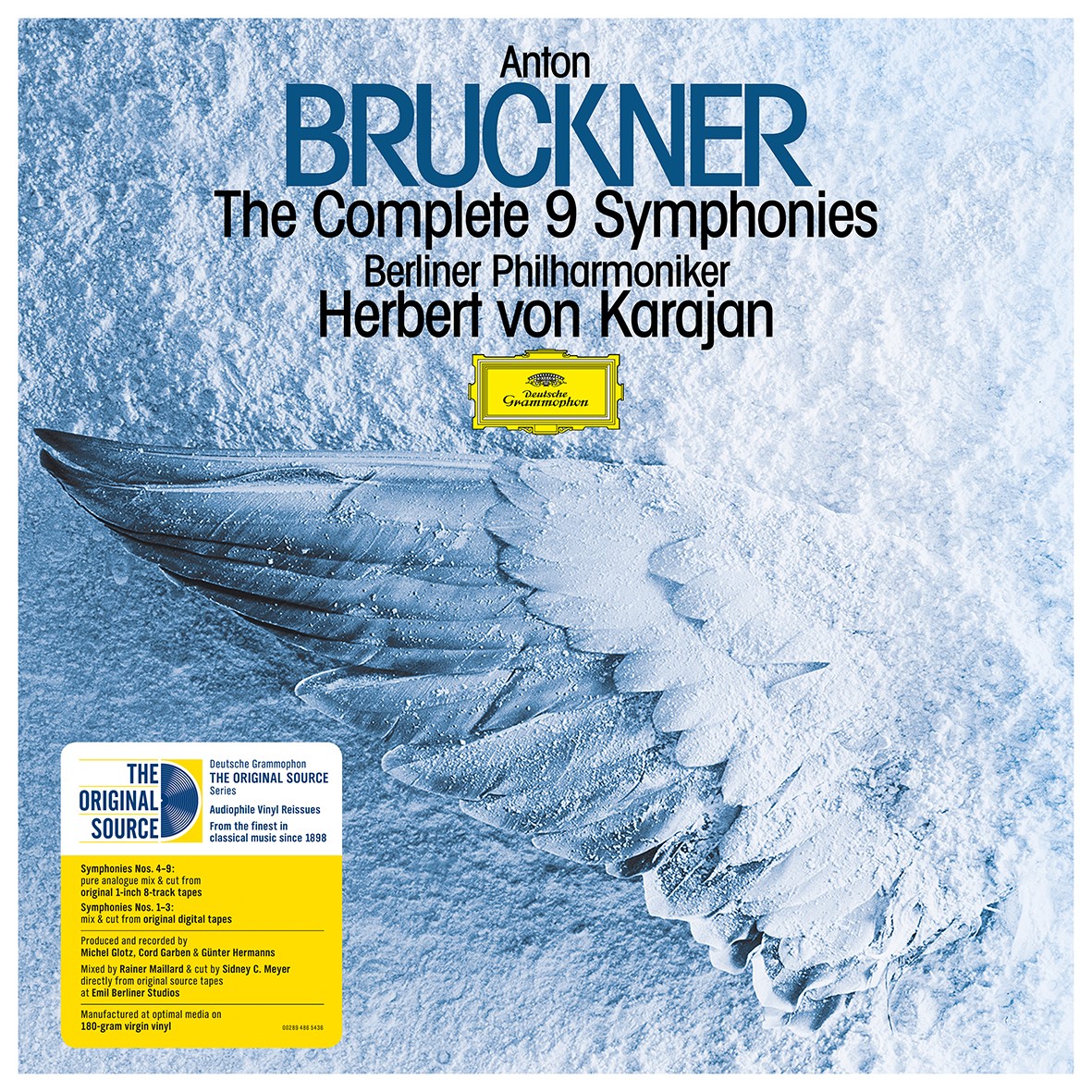

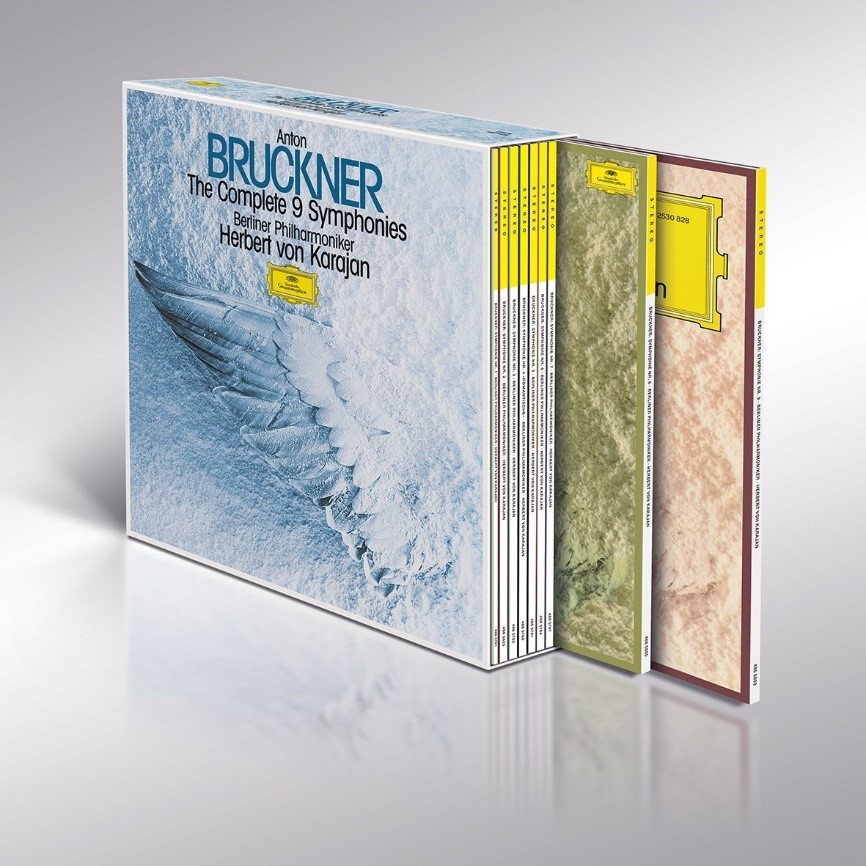

THE PHYSICAL PACKAGE

The first thing to be said about the appearance of this box set is simply how physically substantial and, frankly, ravishing it is to unpack, explore and place on your shelf (see my unboxing video below).

Except that, in this household, my wife declared I should leave it on top of the desk, in full view of anyone sitting or passing through the living-room. There we can all fully appreciate its exquisite artwork and design.

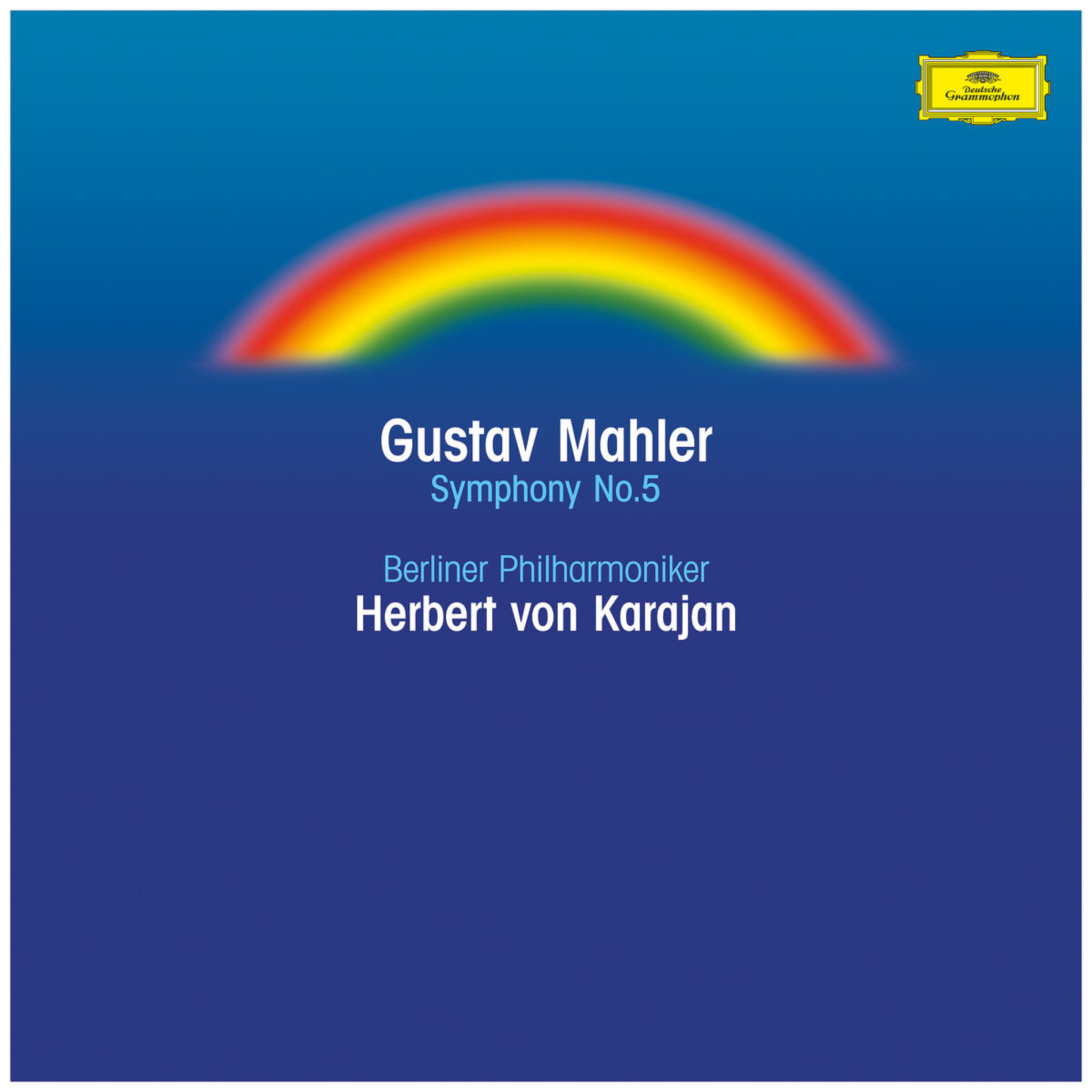

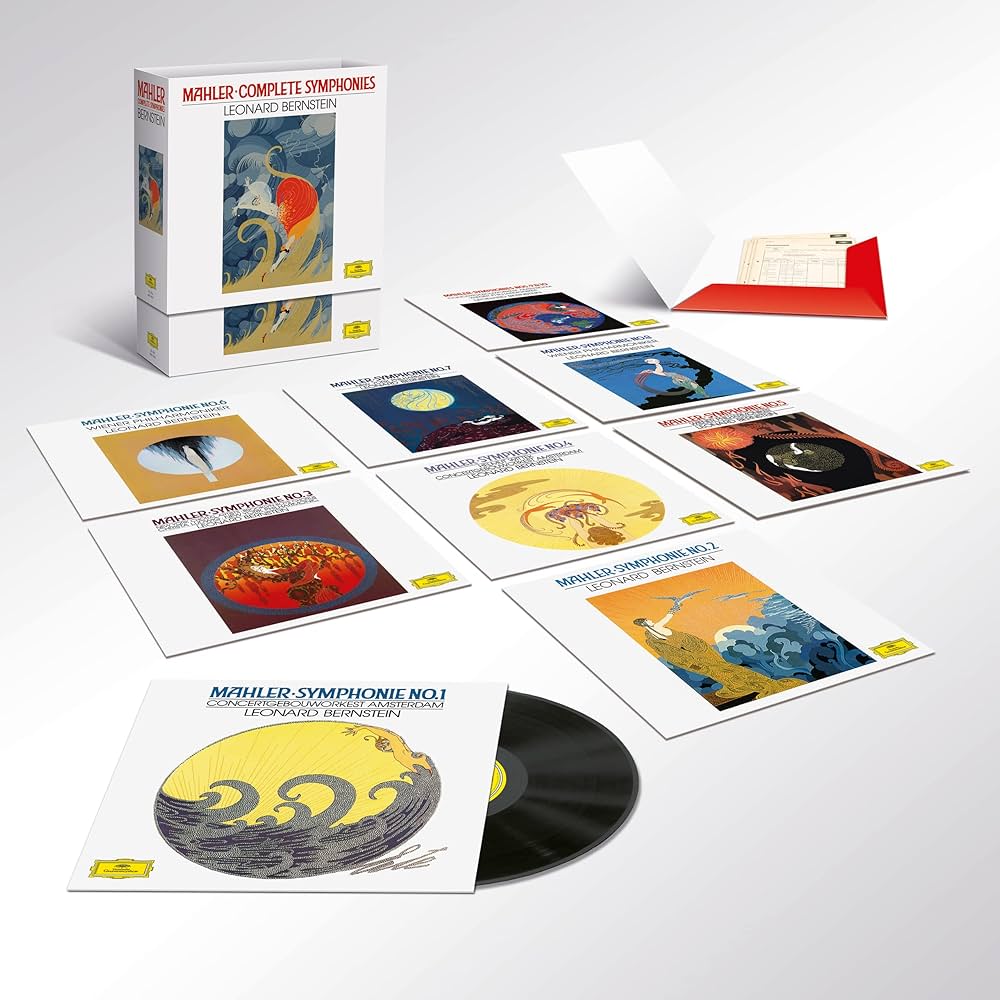

Holger Matthies' "rainbow design" used for Karajan's series of Mahler recordings

Holger Matthies' "rainbow design" used for Karajan's series of Mahler recordings

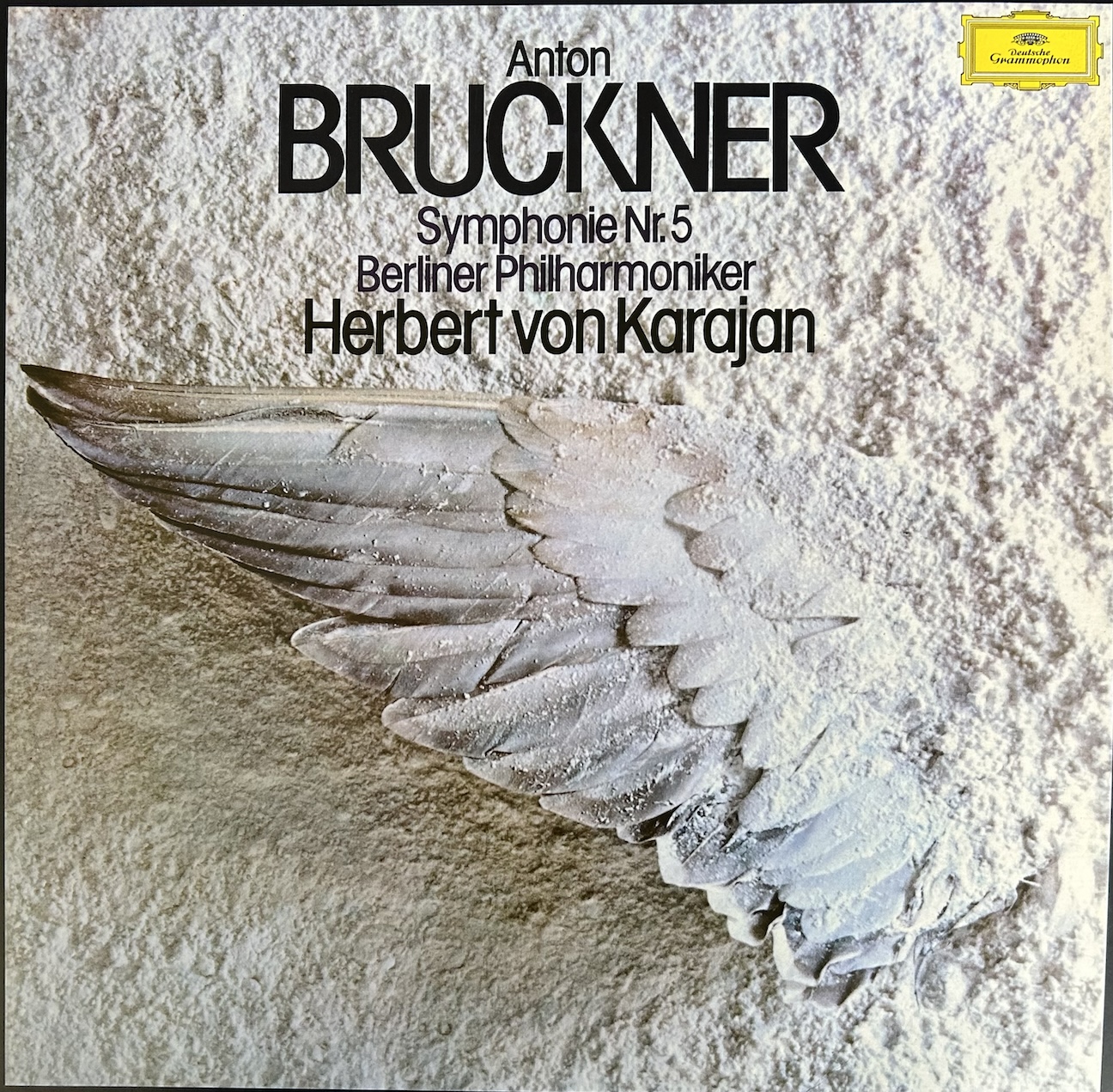

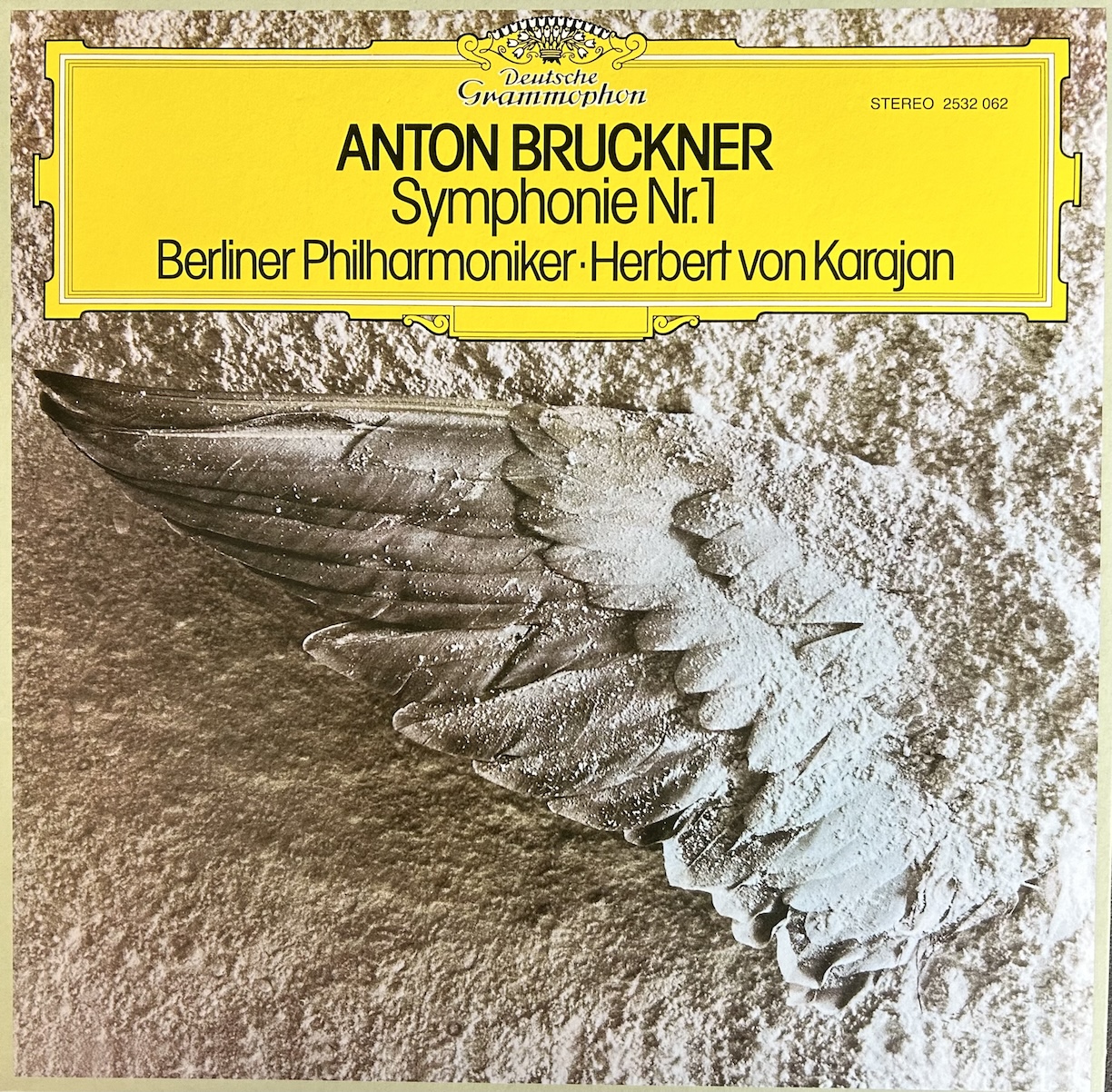

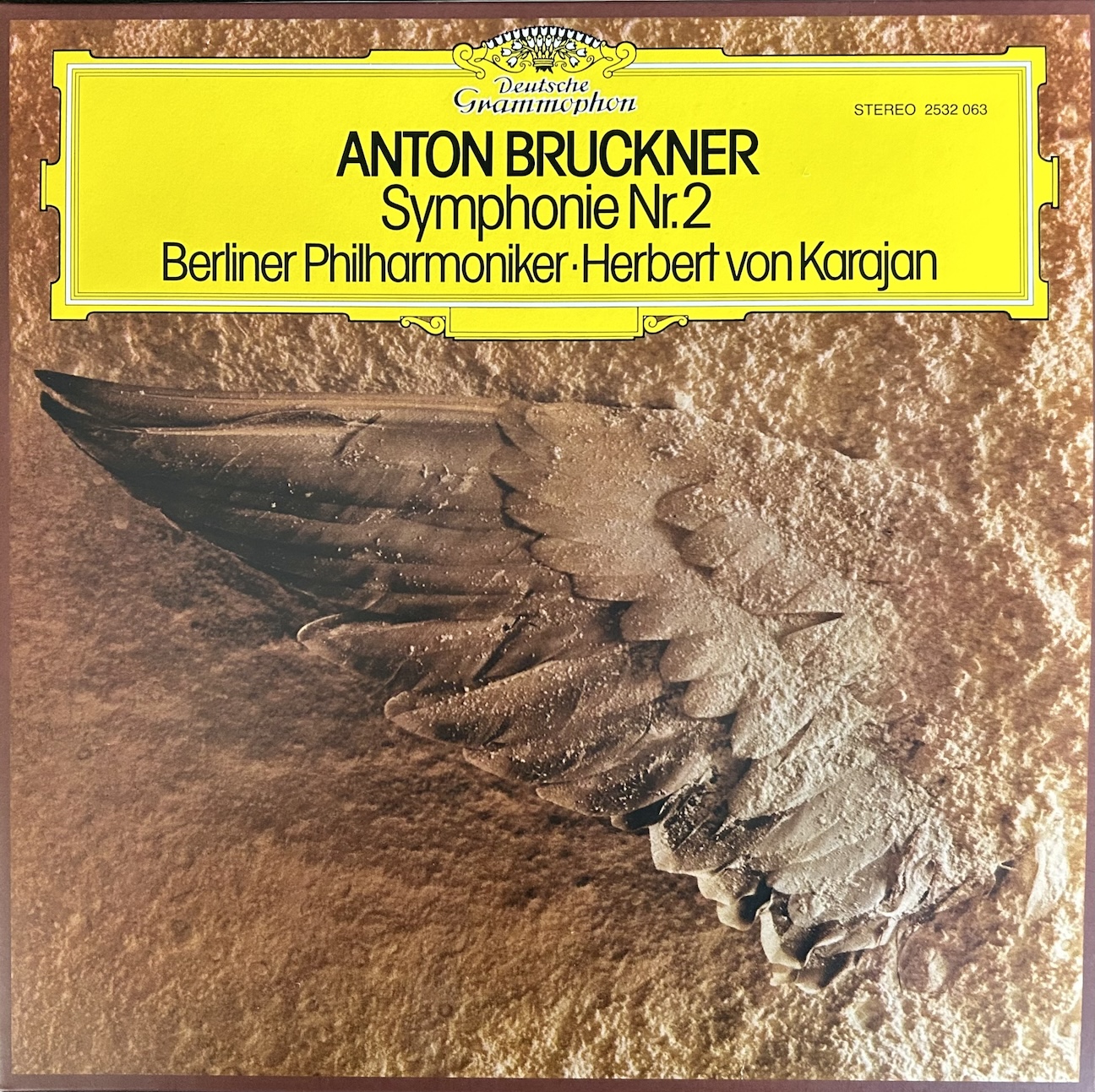

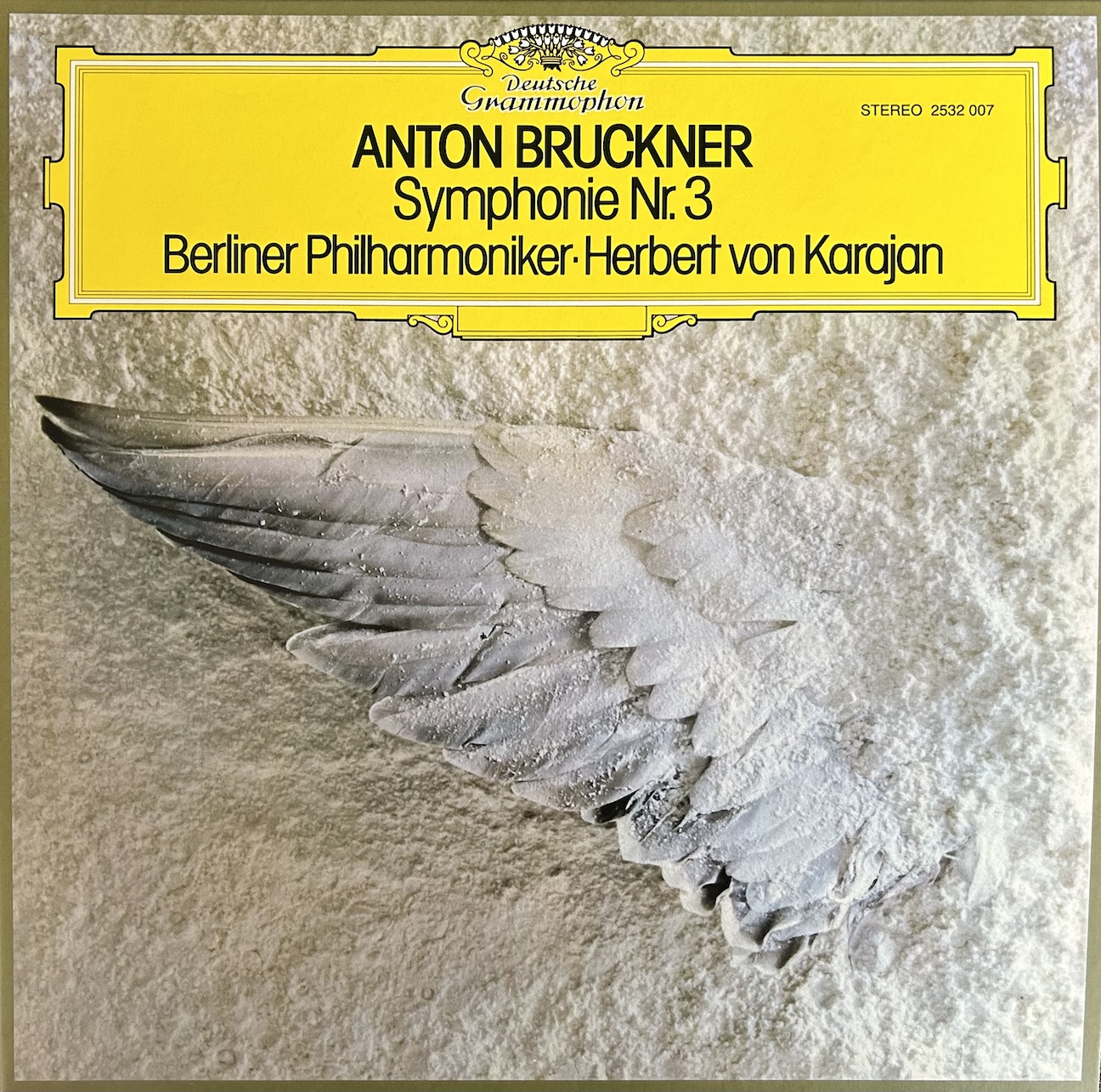

As with Karajan’s series of Mahler recordings, and his later 1980s remake of the Beethoven symphonies, for the original LP releases DG turned to the artist/graphic designer Holger Matthies (still going strong at 84) to come up with a striking, almost abstract album cover design that could be shared across all the different installments of the cycle. He came up with the simple image of an angel’s wing in snow, a brilliant visual encapsulation of Bruckner’s music, in part referencing the composer’s faith. For each release in the Bruckner cycle there is a different color tint to the image, with a commensurate solid color border around the edges of the album cover. For this box set’s cover, and the slipcase that wraps around the box, DG has gone with an exquisite pale blue hue that is very inviting.

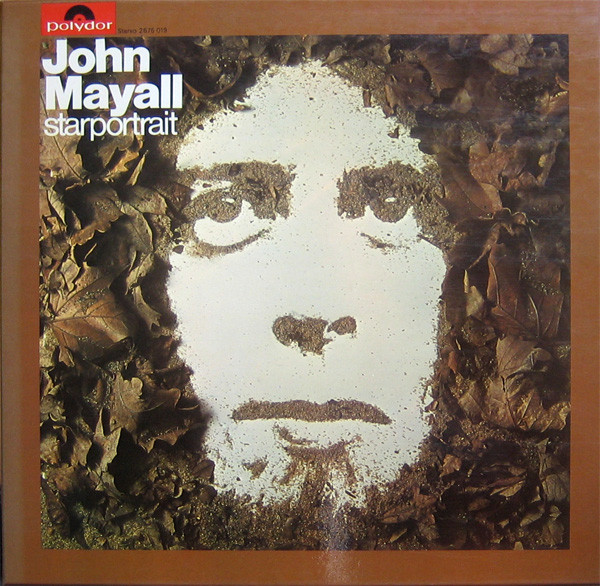

(Go online and check out Matthies’ numerous poster and album cover designs, including one for a John Mayall record; they are most striking. It will be no surprise to learn that he professes a strong influence from the iconoclasm of Polish poster design, and Japanese poster artwork).

Holger Matthies' design for John Mayall's 1971 Compilation

Holger Matthies' design for John Mayall's 1971 Compilation

Keeping to the design of previous releases in the Original Source series, all record sleeves are printed with a matte finish to distinguish them from the gloss finish of the original LP releases. As mentioned earlier, only Symphony 1 is a single LP; the rest are all double LPs, with gatefolds that feature original recording notes and striking photos of Karajan - some of which will be familiar to collectors, others less so. Original sleeve notes are included on the back of each LP, and fortunately this set was blessed with the first rate commentaries of Richard Osborne, still one of our best music writers and an acknowledged expert on Bruckner’s music. His notes are as engaging for the newcomer to this repertoire as they are illuminating for the Bruckner expert. They are only absent for Symphony 9, and are sorely missed.

All records are pressed immaculately on 180g vinyl. My copies were dead silent, and on only two sides did I have to put up with the ingrained defect of a scratch - one for 5 cycles, one for a more annoying 10. Pretty good for a 17lp set - I’m not complaining, but I imagine some of you might - not unreasonably.

DG has done this set proud with a first rate booklet that includes some ravishing photos of the equipment specially designed and built for this project by Emil Berliner Studios, plus some more fine Karajan shots. (It would have been nice to have one vintage shot of the orchestra in the Philharmonie, but that wasn’t in the original booklet either). There are two very informative essays on Bruckner’s music and his relationship with the BPO reproduced from the original 1980s box set booklet - but Osborne’s notes on each individual symphony far eclipse both.

The truly valuable bonus here for audiophiles is the extended essay by Rainer Maillard covering all the technical aspects of the project, plus some additional insights into the “Karajan sound”. I have already quoted much of this in Part 2 of our coverage, and some above, but there’s plenty more not included here for purchasers of this set to dive into. From a historical as well as informational perspective it is so good that DG included Maillard’s extended thoughts here. It’s a good precedent for any future box sets in this series (I greatly missed having a booklet included in the Steinberg box).

While some might lament the fact that this is not a literal “box set”, I for one love these sturdy, slip cased boxes that DG has used for these boxed Original Source reissues, enabling us to retain the original albums and all their individual artwork and notes, plus have the bonus encompassing box with extra photos and artwork.

Like the Bernstein/Mahler symphony set before it, this Bruckner set is something you will be quite happy to leave out where everybody can see it! Collectors should be very happy to possess something of such beauty which showcases the individual records complete with sleeve notes and artwork so well.

The EBS Remastered Set of Mahler's Complete Symphonies, reviewed here by Michael Johnson and, I believe, still available.

The EBS Remastered Set of Mahler's Complete Symphonies, reviewed here by Michael Johnson and, I believe, still available.

IN CONCLUSION

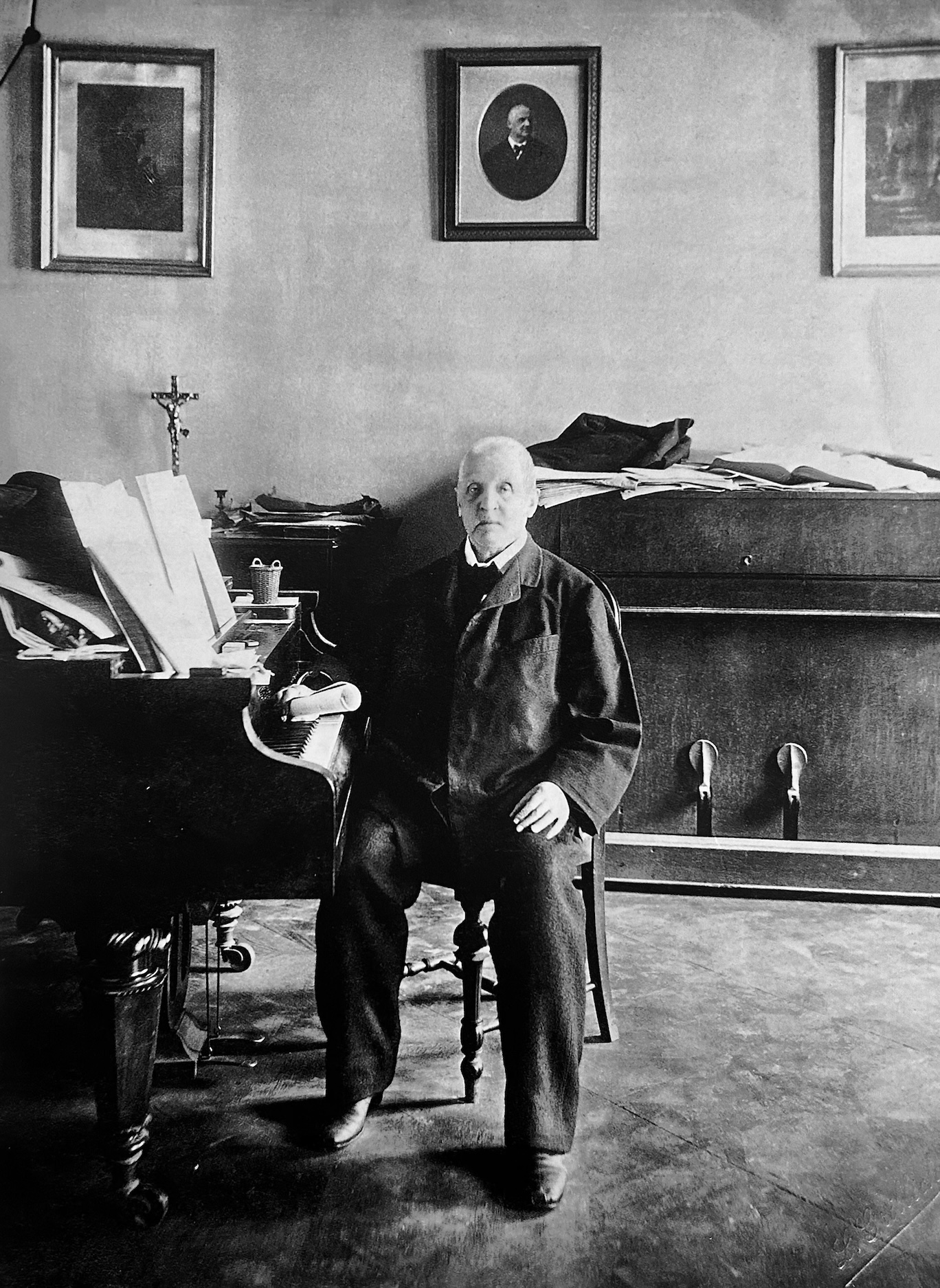

Anton Bruckner in his study at St. Florian's, c. 1890

Anton Bruckner in his study at St. Florian's, c. 1890

If you are a Karajan or Bruckner enthusiast, this set is a no-brainer. The upgrade to the sonics is remarkable even by the already high standards of the Original Source Series, and to have those early digital recordings of Symphonies 1- 3 now rendered more than listenable is a real treat.

Speaking of Bruckner enthusiasts, there are obviously alternatives to this cycle out there. Bernard Haitink with the Concertgebouw on Philips and Eugen Jochum’s two cycles - the first on DG with the BPO and Bavarian Radio Symphony, the second on EMI with the Dresden Staatskapelle - are all benchmarks. I’ve not heard the harder-to-find Gunter Wand complete vinyl set with the Cologne Radio Symphony on Deutsche Harmonia Mundi, but his later versions (with the BPO amongst others) on CD etc. are rightly revered.

And of course there are numerous later digital cycles, plus recordings of individual symphonies that would be considered essential for collectors. I myself would not want to be without the Carl Schuricht /VPO reissues on Testament of Symphonies 3, 8 and 9 (originals will cost you an insane amount), nor Karl Böhm’s 3rd and 4th on Decca (3 on King Super Analogue). I still have a soft spot for Solti’s several VPO sets recorded in the Sofiensaal in the 1960s. One reissue I’m keeping my eyes open for is Knappertsbusch’s 8th on Speaker’s Corner.

But the sonics of this new Original Source reissue set it apart from all others that I have heard, no matter what the format, and, combined with the authoritative nature of Karajan’s interpretations, this is necessarily a set that belongs in the collection of every classical enthusiast who responds to Bruckner’s music.

There is a really special thrill in sitting down to listen to these records, especially if you are a Karajan fan. Make a cup of tea or coffee, or maybe pour something a little stronger; dim the lights, and close your eyes.

As the music emerges out of the black silence, as the primordial sonic soup that so often opens these symphonies coalesces into musical utterance, you are transported back to the Philharmonie in the 1970s in a manner more vivid and immediate than it was possible to imagine before this release. And once there, the genius of Bruckner’s music is laid out before you, and you step into into his world effortlessly. It’s a world that inspires awe and introspection in equal measure, and in today’s secular society it’s good - nay, essential - to be reminded that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in our philosophy.

The Force has indeed Awakened.

You can read Part 1 of this series of articles covering this Bruckner release here, and Part 2 here.

Anton Bruckner: Symphonies 1 - 9

Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Originally Recorded between 1975 and 1981 in the Philharmonie, Berlin

Directors of Production: Günther Breest, Dr. Hans Hirsch, Magdalene Padberg

Recording Supervision: Michel Glotz, Cord Garben

Recording Engineer: Günter Hermanns

Editing (Symphonies 1-3): Christopher Alder, Reinhild Schmidt

Original Source Series Reissue:

Mixed by Rainer Maillard and Cut by Sidney C. Meyer directly from original analogue source tapes (Symphonies 4-9) and from original digital source tapes (Symphonies 1-3) at Emil Berliner Studios

Pressed at Optimal Media

Product Managers: Johannes Gleim, Meike Lieser

Editorial: Jochen Rudelt, Annette Nubbemeyer, texthouse

Design: Nikolaus Boddin

17 LPs in slipcased box, with color booklet. Limited Edition of 2000.

Music: 11

Sound: 10 - 11 (Symphonies 4 - 9)

8 (Symphonies 1 - 3)

Further Resources for the Bruckner and Karajan Obsessive:

abruckner.com - You will be able to disappear down numerous rabbit holes on this site to your heart's content. Essential for anyone wanting to explore all things Bruckner.

The Karajan Institute and Archive - Exactly what is sounds like.

Gramophone Magazine - You can access old reviews and articles here, including Karajan interviews, though for access to some you will need to be a subscriber. A recent addition to the site's podcast is a discussion of Karajan's video legacy with his biographer Richard Osborne, who also remembers some of his personal experiences attending Karajan concerts. Highly recommended (and no subscription needed to listen).

Another of the great Couzot/Karajan filmed collaborations - rehearsal and then performance of Schumann's 4th Symphony. You get a real sense of Karajan's detailed rehearsal method, and then how he just lets the orchestra "go" in the performance. All beautifully (and musically) filmed by Clouzot, one of the great French film directors of his time.

Available for pre-order at AcousticSounds.com