John Culshaw at 100 - 10 Essential Recordings

Celebrating the great Classical Producer with 10(+) of his greatest recordings

The names of the foremost producers in the world of classical music recordings generally are known primarily to those in the biz, and to collectors. However, John Culshaw’s is the one name who broke through to the more general public, and with good reason. His legacy - primarily with Decca - includes many of the most celebrated classical recordings ever made, several of which enjoyed huge sales on the level of pop and rock albums, and became cultural touchstones still remembered today. Think the first complete studio Wagner Ring cycle, recorded with conductor Georg Solti and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Britten War Requiem.

Why was Culshaw so important, and why does his work continue to attract such accolades?

First of all, he was fortunate enough to work in the classical record industry as the long playing record came into being, and then with the dawn of the stereo age and its associated technological advances, he was in a position to bring classical music into the homes of the burgeoning record buying public, with a level of sonic fidelity hitherto unknown.

Secondly, this explosion of interest in home HiFi coincided with the maturing of a new generation of exciting conductors, soloists, and the increased polish of orchestras (now recovered from the privations of World War II).

Thirdly, allied to both of these factors, there was a seemingly bottomless appetite for new recordings of central classical repertoire and beyond. Once record enthusiasts realized how good the new Mono and then Stereo LPs could sound (with far fewer side breaks than cumbersome 78s), then they wanted the universe of classical music available at home, instantly accessible.

None of these factors would have ensured Culshaw’s singular preeminence if it hadn’t been for the unique qualities he brought to the table as a producer.

As a boy growing up in Britain during the 1930s, music would have been part of his education and early on he displayed a real passion for it, especially for the music of Rachmaninov (after leaving Decca he wrote sleeve notes for a clutch of Vladimir Ashkenazy’s early Rachmaninov records on the label). As a serviceman, when on leave he developed a friendship with the Pollard family, which was closely associated with the Gramophone magazine, and it was that publication that ran an article by him about Rachmaninov in 1945.

After the War it was the Pollards who helped him begin a career in the recording industry, at Decca, which was the burgeoning upstart to the more established EMI Gramophone Company.

Culshaw was a born collaborator and excellent team leader, skills learned during his days serving as a navigator in the Fleet Air Arm during the War. He moved rapidly from the publicity department to becoming a producer: “I loved the atmosphere of the studios and the new experience of very close proximity to music-making”, he wrote in his autobiography.

Culshaw fully understood the importance of recognizing engineering talent, and, when identified, encouraging it to go the distance. He was also humble enough to heed the advice and guidance of his engineers, while also pushing them to try new things. His work with Kenneth Wilkinson, with whom he first worked on some of his earliest sessions as producer, is rightly celebrated, but he also understood the virtue of nurturing new talent, and giving younger engineers opportunities - exemplified in his decision to let Gordon Parry lead the team that recorded the Ring cycle.

As a result, with a John Culshaw recording you will be assured of the very best sonics. It’s no exaggeration to say that he was an indelible part of establishing the “Decca sound”, which remains a benchmark of excellence for anyone working in classical music recording.

Similarly, he had an unerring instinct for identifying performing talent - especially conductors - who would be well suited to the record medium. Herbert von Karajan already had a notable catalogue of recordings behind him at EMI when he was persuaded to start recording with Decca in the 1950s with the Vienna Philharmonic. His work for that label achieved a level of excellence which - many would argue - remained unsurpassed even after he moved to Deutsche Grammophon. Much of that Decca catalogue was undertaken under the watchful eye of Culshaw.

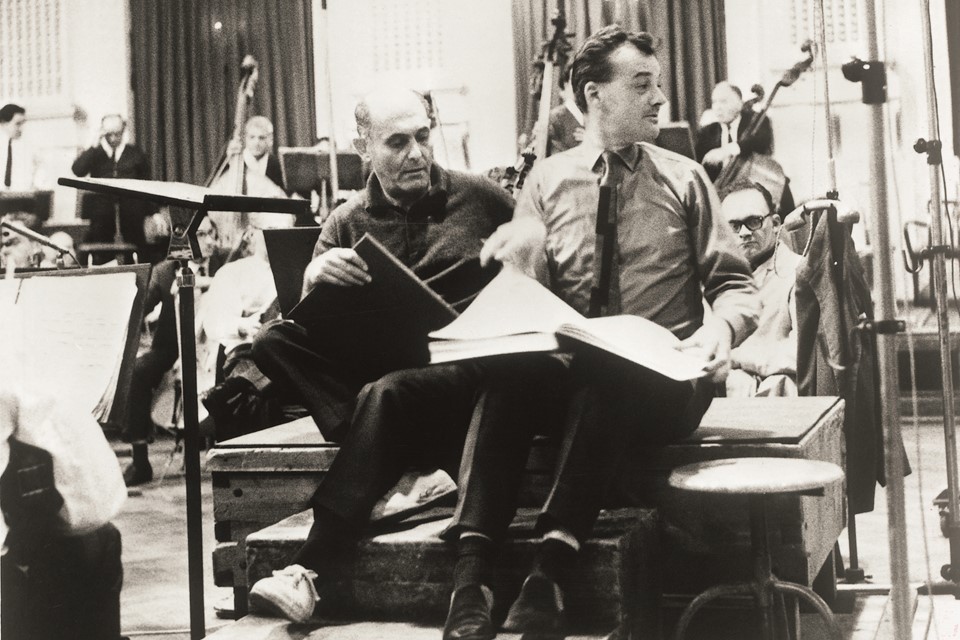

Georg Solti and John Culshaw (photo: Decca)

Georg Solti and John Culshaw (photo: Decca)

Similarly, Georg Solti was a relative unknown when Culshaw began recording him with the VPO and the still nascent Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. Choosing Solti to helm the label’s Ring cycle flew in the face of many more established (and older) Wagnerians, but Culshaw rightly surmised that Solti’s unique blend of energy and showmanship was just what this daunting project needed to make it fly.

Culshaw also oversaw important sessions with Ernest Ansermet, Hugo Wolff, and Pierre Monteux.

Culshaw had an ear for pianists, as witness his early sessions with Clifford Curzon and Julius Katchen, and later on - after leaving Decca - he championed Vladimir Ashkenazy.

But it was in the realm of opera recordings where Culshaw made the biggest impact. He would have none of the respectful, “opera in concert” approach of the other labels. He was all about making the drama come alive in the listener’s living-room (but without sacrificing any of the purely musical aspects of the work in question). He mapped out a grid in the studio so that the singers could move around in the stereo space and interact with each other. He was happy to incorporate live and taped sound effects, and manipulate aural perspectives. This approach came to be known as SONICSTAGE, and was emblazoned on the covers of his later productions. Listen to any of his opera recordings and they are exciting as hell!

In Gramophone’s recent tribute to Culshaw, Michael Haas, who joined Decca as a producer in 1977, made these comments about Culshaw’s approach to recording opera:

“Culshaw saw opera as theatre, and there was nothing objective about theatre; and sound-analysis served the single purpose of achieving the sense, or feel, of the theatre… To create this feel, he and his crew came up with what I can only describe as the acoustical vanishing-point - it was to recording what Filippo Brunelleschi’s achievements in the early 15th century were to painting.”

This was the Decca “tree”.

“It offered a depth to recording which more objective and analytical recordings had failed to capture. Culshaw saw opera as something more important than the mathematics of ensemble and intonation. He wanted visceral interaction to come across, and this involved use of the acoustical vanishing point. Takes were long so that dramatic dynamics between protagonists could be created - and so what if each take was fundamentally different? That was the very nature, the soul, of performance.”

It was, essentially, an approach to recording opera that had much in common with recording radio drama. When I was first producing and directing radio drama for NPR in the late 1980s and early 1990s, we did not have the luxury of multi-track. We were recording everything live to early 2-track digital, not just in the studio but also - often - onstage in front of an audience. Having been a fan of Culshaw’s opera recordings since my teens, I fully embraced his approach, drawing out a grid on the stage, carefully mapping out positions for my actors (and occasionally sound effects technicians). Our main microphones were a stereo pair at the front of the stage, so everything was recorded in relation to that single perspective, the same perspective of the eventual listener at home. This was identical to what Culshaw did with the Decca “tree” placed above the conductor’s head.

It was a wonderful way to work, because it meant the actors could “be” both in the physical and, by extension, the aural space of the drama, and relate to each other physically. And if there was an audience, it could watch a partial staging that aligned with what they were hearing. Later, as we moved to multitrack and therefore a series of stationary mics, with most of the changes in perspective being created in “post”, what we gained in fidelity we also lost in vibrancy. (I often yearned to return to the older way of doing things).

To listen to a Culshaw opera recording is to fully enter the drama with no filter or compromise, with an immediacy which can even rival or surpass the experience of seeing the same work in the opera house. There are no visual distractions - your imagination is left to do the work. Certainly in the case of Wagner’s gods and heroes, scenes of myth and fantasy, not having the action presented literally in front of your eyes can be a real advantage when it comes to suspending disbelief.

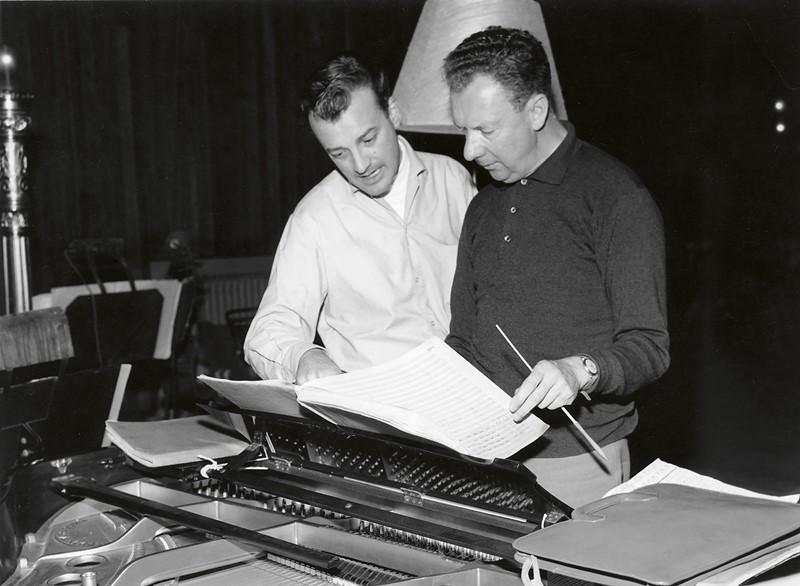

John Culshaw and Benjamin Britten (photo: Decca)

John Culshaw and Benjamin Britten (photo: Decca)

I have left until last what is probably Culshaw’s greatest legacy: his collaboration with Benjamin Britten. I can think of no other contemporary composer who enjoyed such a fully fledged, close relationship with a record label, to the extent that nearly all his major works received superb (and many still definitive) recordings, often within a mere few years of their composition. Beyond the conducting and playing of his own works, Britten - who was very unsure of his own abilities as a conductor - was encouraged and cajoled by Culshaw to record key works by his favorite composers, resulting in a slew of benchmark recordings ranging from the well-known (Mozart symphonies, Bach’s St. John Passion and Brandenburg Concertos) to the lesser-known (Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius), to the downright obscure (Schumann’s Scenes from Goethe’s Faust). (Some of these took place after Culshaw left Decca in 1967).

After parting acrimoniously from Decca, which, to its eternal discredit, failed to realize his true worth to the company by offering him a position commensurate with his value, Culshaw joined BBC Television where he continued in his pioneering efforts to bring classical music to as wide an audience as possible. He shepherded André Previn’s Music Night onto the air, where it remained for some years as a huge ratings success. The apogee of his commitment both to opera and new music was commissioning an opera from Britten specifically for television, Owen Wingrave, which I not only saw as it was first broadcast in 1970, but then at its premiere theatrical performance at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden (with my ‘cello teacher playing in the orchestra).

In making my selections below, I have cheated somewhat by omitting the Wagner/Solti Ring, and the Britten War Requiem, both because they are such known quantities, but also because I have written about them extensively already for this site. If you want to learn more about what made Culshaw so special, I highly recommend you seek out those articles (linked above), which cover not only his work in the studio but how he shepherded these recordings to market and made them such huge commercial successes. Beyond that I highly recommend reading his autobiography, Putting the Record Straight, and his account of the Ring project, Ring Resounding.

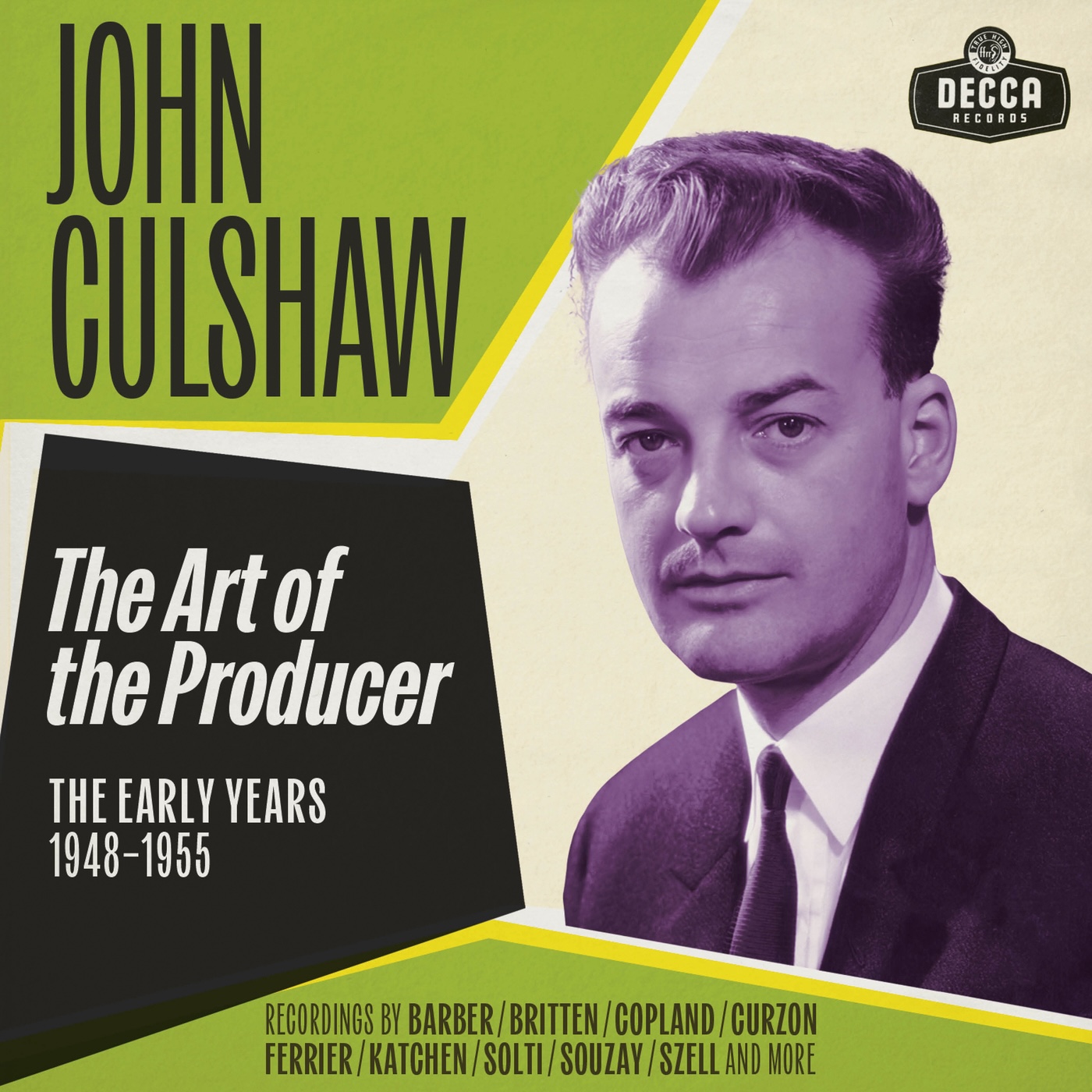

In making my selections I have stuck with the stereo era on Decca (and I must confess I have cheated a little by mentioning in passing additional recordings beyond my chosen 10 - couldn’t help it, there are so many riches here). For anyone wanting to dive into his lesser-known mono work, the always splendid Eloquence Classics has just released a marvelous box set, titled The Art of the Producer - The Early Years, which also includes an extensive detailed essay about Culshaw by current Decca producer Dominic Fyfe. (Hopefully Eloquence will release a second box focusing on Culshaw’s later work).

One final word. In researching this I relied in part on Culshaw’s discography as listed on Discogs (as well as looking at my own copies of records). Discogs is not the most reliable source on such matters - if anyone knows of a more accurate listing, do please share that knowledge. Some records have him listed as an uncredited producer. I have tried to stick as closely as possible to what I know are records he produced personally. Having said that, it’s fair to say that during his tenure at Decca (and even after he left) his influence was pervasive, his ideals for the recording process followed and venerated, and it’s one of the reasons classical collectors have come to treasure the Decca catalogue of the 1960s and 1970s as we do.

In the list that follows I am sure there will be some old favorites familiar to many of you, but hopefully also some surprises. In all cases, this is a legacy of unparalleled richness: timeless and worthy of celebration by each new generation of listeners that discovers it.

The records are presented in no particular order.

Enjoy!

This is one of a clutch of early stereo Deccas highly prized amongst collectors for their transparent sonics and, in this case, the highlighting of a major conducting talent. Ataúlfo Argenta’s career was cut short at the young age of 44 by carbon monoxide poisoning in his car. The sequence of events leading up to his death remain murky. When I was reviewing the recent Original Source reissue of Ozawa’s stunning traversal of this work, I mentioned this rendition as a worthy alternative, not least for the sonics of the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra giving us that “authentic” 1950s French orchestral sound. Seek out the fine Speaker’s Corner reissue, or the UK-pressed London - an original will cost you a ton. Those determined collectors amongst you (with deep pockets) should track down the fine Alto box gathering together Argenta’s early Spanish Deccas, a treasure trove of fine performances of some lesser-known music, beautifully recorded.

There’s a clutch of recordings by Albert Wolff in Culshaw’s discography, all exceptionally fine with fabulous sonics (and all reissued by Speaker’s Corner), but I plumped for this one showcasing a French orchestra (again), but this time in Russian music. This was a Decca hallmark at the time: French orchestras playing Russian music (think of the matchless Ansermet/Suisse Romande catalogue). Since Russian orchestras themselves were largely unavailable to non-Soviet labels at this time, the French orchestras were the next best thing with their own distinctive brass and woodwind sonorities. This is a marvelous rendition of Glazunov’s typically glittering showpiece, and it all sounds gorgeous in that quintessential early Decca sound.

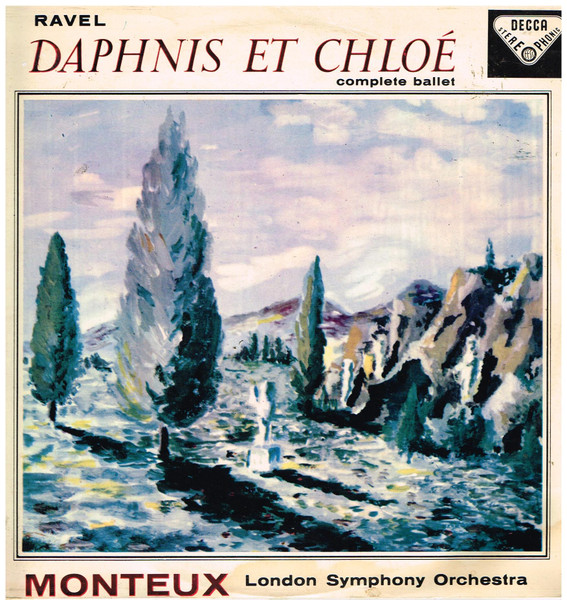

I’m sticking with France for this legendary version of Ravel’s luminous ballet, with the London Symphony Orchestra putting on their berets and crumbling their croissants to the Parisien manor born. Decca has produced two benchmark versions of Ravel’s masterpiece - this one and the early digital extravaganza with Charles Dutoit and the Montreal Symphony in 1981. For the analogue verities this is the one to go for, especially if you can track down the ORG 45rpm cut by Bernie Grundman. You will be drowning in sonic soufflé. (Also well worth seeking out is Monteux’s fine pairing of Haydn symphonies with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, originally recorded by Culshaw and Decca for RCA in 1960, but most cheaply available on a fine UK Decca Eclipse reissue).

Culshaw championed the career of Georg Solti early on, and Solti repaid his faith with a lifelong contract with Decca, and Decca alone. Beyond the ground-breaking Ring cycle, Solti’s early discography is peppered with some fine orchestral albums with the Vienna Philharmonic (including a clutch of brilliant Beethoven recordings of Symphonies 3, 5, and 7) and, as here, with the Israel Philharmonic, which at this time was hardly at the top of anyone’s list of the top international orchestras. I happened upon an original wide-band pressing of this some 25 years ago, and it remains a favorite (although on some systems it might sound a little bright). These are thrilling, very Solti-esque renditions of these two warhorses, but boy do they sing in.that glorious Decca sound of the period - which is catnip to this collector. If you happen upon this in any of its incarnations, do not hesitate.

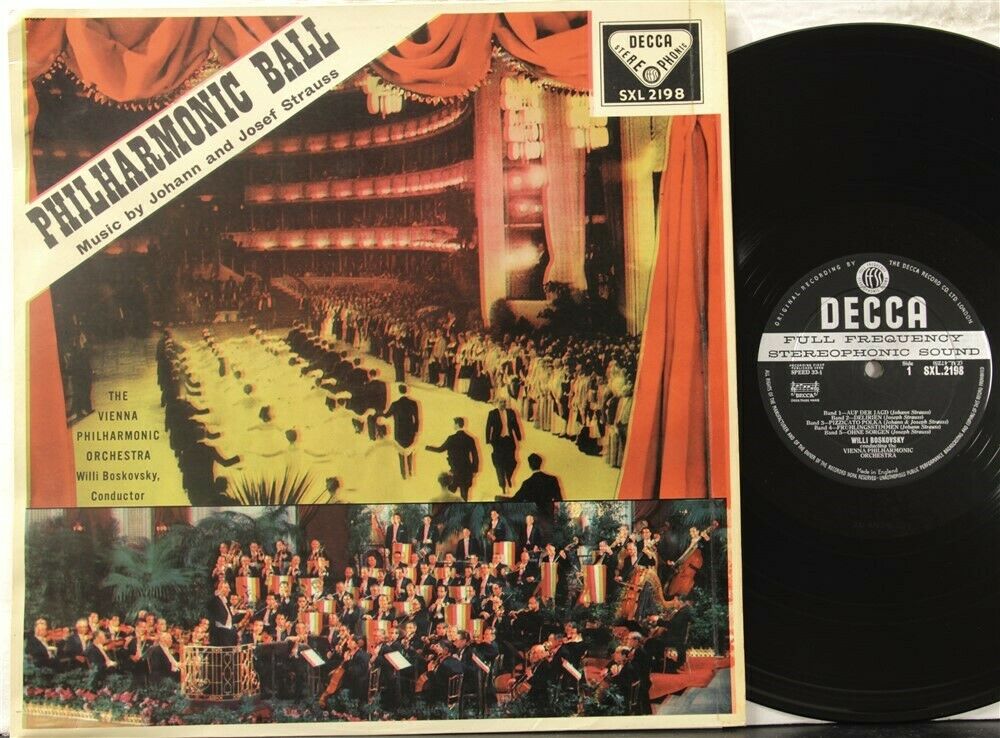

Staying with Culshaw in Vienna, here’s an early entry in what would become a long-running series of quintessential Strauss family albums, delivered by the Strauss orchestra par excellence conducted by their concertmaster, Willi Boskovsky. What can I say? The Blue Danube, the sonics of the Sofiensaal (which by this time Culshaw and the Decca engineers knew backwards), and you are in Vienna on New Year’s Day every time you drop the needle on this record. Pure magic! (If you want to get these VPO/Boskovsky records on a budget, seek out the World of Johann Strauss Vols. 1 and 2 budget reissue compilations - they sound splendid).

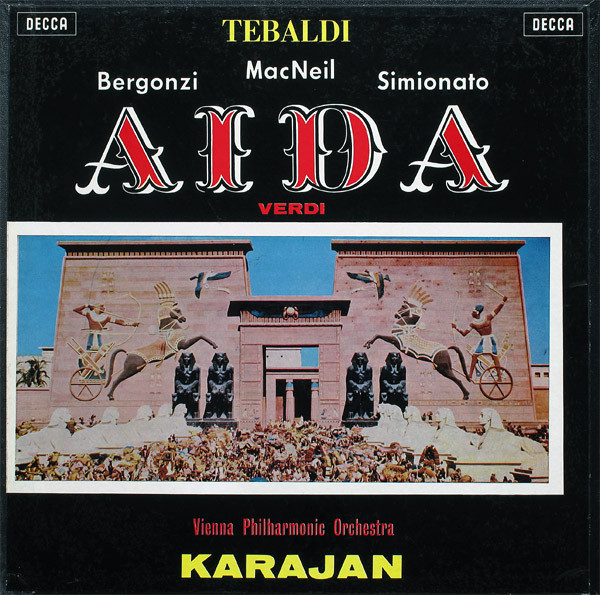

When it came to recording Karajan for Decca, the VPO was the house band. All of the conductor’s recordings from this time are, for me, essential. Shall I mention Also Sprach Zarathustra (used on the soundtrack for 2001: A Space Odyseey), or Holst’s The Planets, or a real personal favorite, Dvorak’s 8th Symphony (gorgeous! gorgeous! gorgeous!!!)? But then there’s this Aida, recorded a year after Solti’s Das Rheingold, which brings together Karajan’s serious opera chops, an unbeatable cast, and Culshaw’s unerring instincts for capturing dramatic lightning in a bottle (or at least on tape). It’s still the Aida everyone should have in their collection (along with Muti’s superb EMI rendition from the 1970s), and if you can track down the immaculate Speaker’s Corner reissue you will be in opera heaven. It’s more Cecil B. de Mille than Cecil B. de Mille!

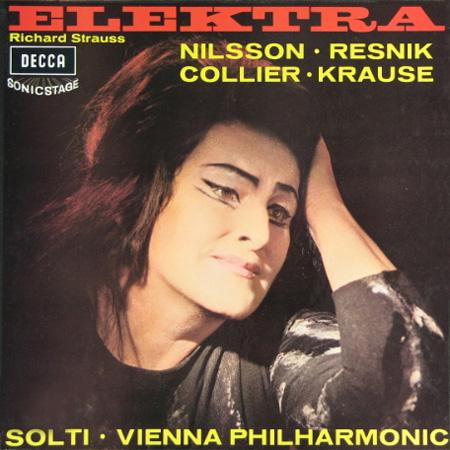

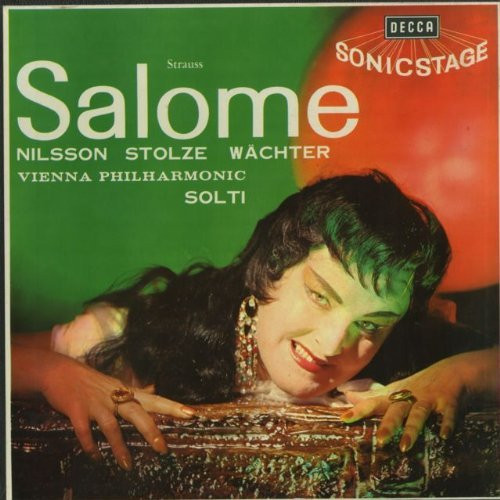

Ok, time for the Big Guns. If you really want to know just how mind-blowingly, gut-wrenchingly fabulous; orgiastically sexy; pulverisingly thrilling opera can sound on your stereo then these are the two sets for you. (Yes, I cheated by lumping them together as one choice). Both operas established Strauss’s credentials as the most shocking artist in Europe, and Elektra helped usher in the 20th Century in music and art. Succés de scandale doesn’t even begin to cover it. These works take the Old Testament and Greek Drama, inject them with an overdose of über-Freudian psychology and acting-out, and voilá: you’ve got a half-naked, hyper-sexed vixen making love to the severed head of John the Baptist in Salome, and “Murder and Mayhem - Family Style” in the Elektra homestead. All brought to you in sonic technicolor by Solti and the VPO on steroids, Birgit Nilsson hitting every high note with laser-beam precision, plus a cast of Opera’s Very Best singing their lungs and brains out, with Culshaw and his engineering team pushing the “Sonicstage” to its very limits. Put on the last side of either opera at full blast and I defy you not to experience full-on “shock and awe”. Goosebumps and panting will ensue. I have seen no stage production of either opera come close. Yes, these recordings are really that good. OG wide band pressings are the ideal. A Speaker’s Corner reissue of Elektra is still out there.

DO. NOT. HESITATE.

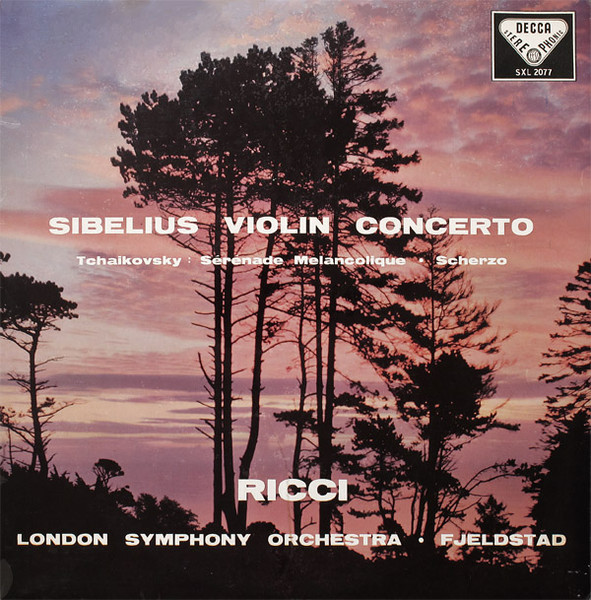

Ok, let’s calm down a bit. Most audiophiles will own the essential Heifetz version of this work on RCA Living Stereo. But the Sibelius Violin Concerto is one of those works I am always wanting to hear in different versions, and I love this recording by one of Decca’s regular star violinists, Ruggiero Ricci. It’s an old-fashioned sound and approach, with a beautiful, quasi-bel canto violin tone. Plus it’s conducted by Øivin Fjelstad, who also helmed Decca’s classic Peer Gynt incidental music released a year earlier in 1958. It’s a more intimate, less intense reading than Heifetz, conjuring up a less forbidding but no less evocative Scandinavian landscape of empty wastes and grey vistas. The Speaker’s Corner version will deliver all the sonic beauty you will need, but ion you must have a wide-band original check your bank balance first.

In conclusion, a clutch of Britten records, all magical and special in their different ways.

Peter Grimes may be the acknowledged classic, the work that put Britten onto the international map, but Billy Budd for me (and many others) is his true operatic masterpiece. The concision and intensity of the drama, confined to a British Man O’ War at sea; the all-male cast crammed together under stress; the simple tale of Evil vs. Good, of redemption through unexpected forgiveness; all underlined in Britten’s masterful use of voices and orchestra which never flags - this is all captured on vinyl by Culshaw and his team in the most direct and thrilling manner. In the hanging scene the lump in your throat will almost stop you breathing. This leaves me an emotional wreck every time I hear it.

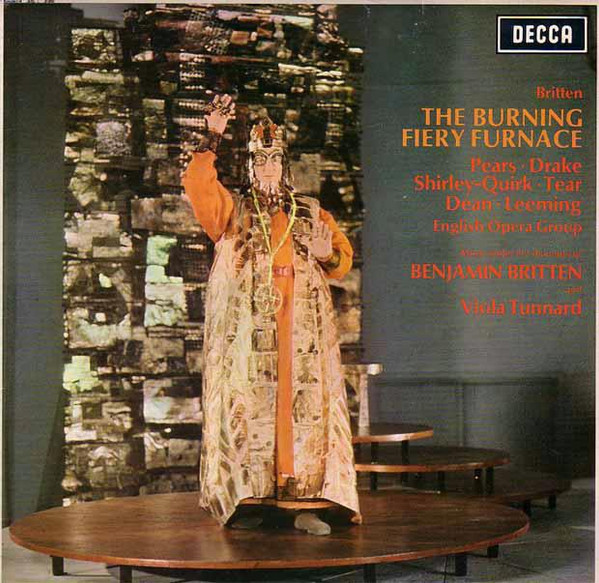

Britten felt his opera writing had stagnated when a visit to Japan in 1956 exposed him to the Noh drama. He reinvented the concept for his series of three Church Parables, with a simplified stage presentation to be performed in church. These works reinvigorated his imagination and musical style, setting the stage for the masterpieces of his later years. The second of these parables (and my personal favorite) was The Burning Fiery Furnace, and Culshaw’s production, recorded in St. Bartholomews Church, Orford, near Britten’s home in Suffolk, beautifully captures the intimate space of the drama. Of special mention is the instrumental sequence where the small band of musicians marches around the Church, deftly captured by Decca’s engineers.

I will utter the heresy of stating that given a choice between watching Shakespeare’s play (yet again) or listening to Britten’s opera in this recording, I’ll gladly opt for the latter. Britten, as in the War Requiem, clearly delineates between the three worlds of the action - the Athenian Court and its mismatched lovers, the “rude mechanicals”, and the fairy realm. He achieves this by employing characteristically imaginative use of colorful orchestration and musical pastiche in service to his own accessible musical idiom and brilliant word-setting. And, as with the War Requiem, Culshaw and his team capture those different realms with distinct spatial and atmospheric clarity on tape. This is simply a magical recording on every level, with definitive vocal performances (especially the suitably otherworldly timbres of counter-tenor Alfred Deller as Oberon). The play within a play at the end - Pyramus and Thisbe - is still hysterical after years of listening to it The finale - all fairy dust forgiveness, plus the original anarchist Puck winding up the proceedings with the brilliant solo trumpet of the LSO’s William Lang ringing out clear as a bell - winds up the phantasmagoric proceedings as beguilingly as any midsummer misadventure you may have experienced in your own misspent youth.

It’s as good a place as any to conclude this homage to a body of work in the recording arts that stands the test of time as well as - if not better than - any other.

Happy 100th to John Culshaw!

(And do please add any suggestions of Culshaw records you especially love in the comments below).

Box Set of Culshaw's Early Recordings from Eloquence Classics

Box Set of Culshaw's Early Recordings from Eloquence Classics