Giulini Meets Bruckner: DG’s Classic Recordings by the Italian Maestro Given New Life on Vinyl by Emil Berliner Studios - Part 1

The Philosopher Poet of the Podium meets the Arch Austrian Romanticist in Vienna, and the result is something very special for the Bruckner Bicentenary

When it comes to the classical Big Guns - by which I mean, Big Orchestras, Big Works, LONG works - it doesn’t get much bigger (or longer) than Gustav Mahler and Anton Bruckner.

Straddling the height of Romanticism in the 19th century, squeaking into the 20th century (that would be Mahler, who died in 1910), their Nine Symphonies - all composed for huge orchestras (with added choirs and soloists in the case of Gustav) - are the final, glorious statement of late-Romantic, symphonic world-building. What Wagner was to opera - pushing boundaries, experimenting within old forms, creating new ones - Bruckner and Mahler were to the symphony.

And these days both are the darlings of the record industry. Everyone and their nephew has recorded complete cycles, partial cycles, multiple cycles of these pinnacles of large orchestral blockbustery musical epic-ness.

Bruckner and Mahler are the Jurassic Park T-Rexes of the classical music industry - stomping on the competition - both on record and in the concert hall. People seemingly can’t get enough of the Big B and M these days. Only the comparatively miniature Baroque specialists slip between their legs to similarly drive up sales figures and fill concert halls and opera houses. What an odd fact that is!

’Twas not always thus. In fact, the Bruckner-Mahler juggernaut is a comparatively recent phenomenon. The first complete recorded cycles of Mahler didn’t emerge until the 1960s and 70s - courtesy of Bernard Haitink and the Concertgebouw of Amsterdam on Philips, and Leonard Bernstein with the New York Philharmonic on Columbia (CBS). Bruckner intégrale arrived via Deutsche Grammophon with Eugen Jochum, followed by Haitink again in Amsterdam on Philips.

Interesting that these two composers are so readily lumped together. Their music is actually very different. Bruckner is the teutonic (ok Austrian) traditionalist in so many ways, thoroughly and consciously in the Beethoven line of succession. Mahler is the iconoclast, the harbinger of 20th century modernism/post-modernism.

Of the two, it’s Bruckner who’s having his Big Moment right now, because it’s the 200th anniversary of his birth.

Anton Bruckner

Anton Bruckner

All the Bruckner Big Guns are out there finishing up their latest cycles - Christian Thielemann, Andris Nelsons, Markus Poschner et al. The record companies are having a field day with new releases, reissues etc.

All of these modern-day Bruckner guys have their fans and detractors. But if you really want to get to the good stuff, the REALLY good stuff, look no further than two major Bruckner releases coming out on vinyl courtesy of Deutsche Grammophon, and the engineering/mastering/cutting wizards over at Emil Berliner Studios: Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer.

Sidney C. Meyer (l.) and Rainer Maillard at Emil Berliner Studios

Sidney C. Meyer (l.) and Rainer Maillard at Emil Berliner Studios

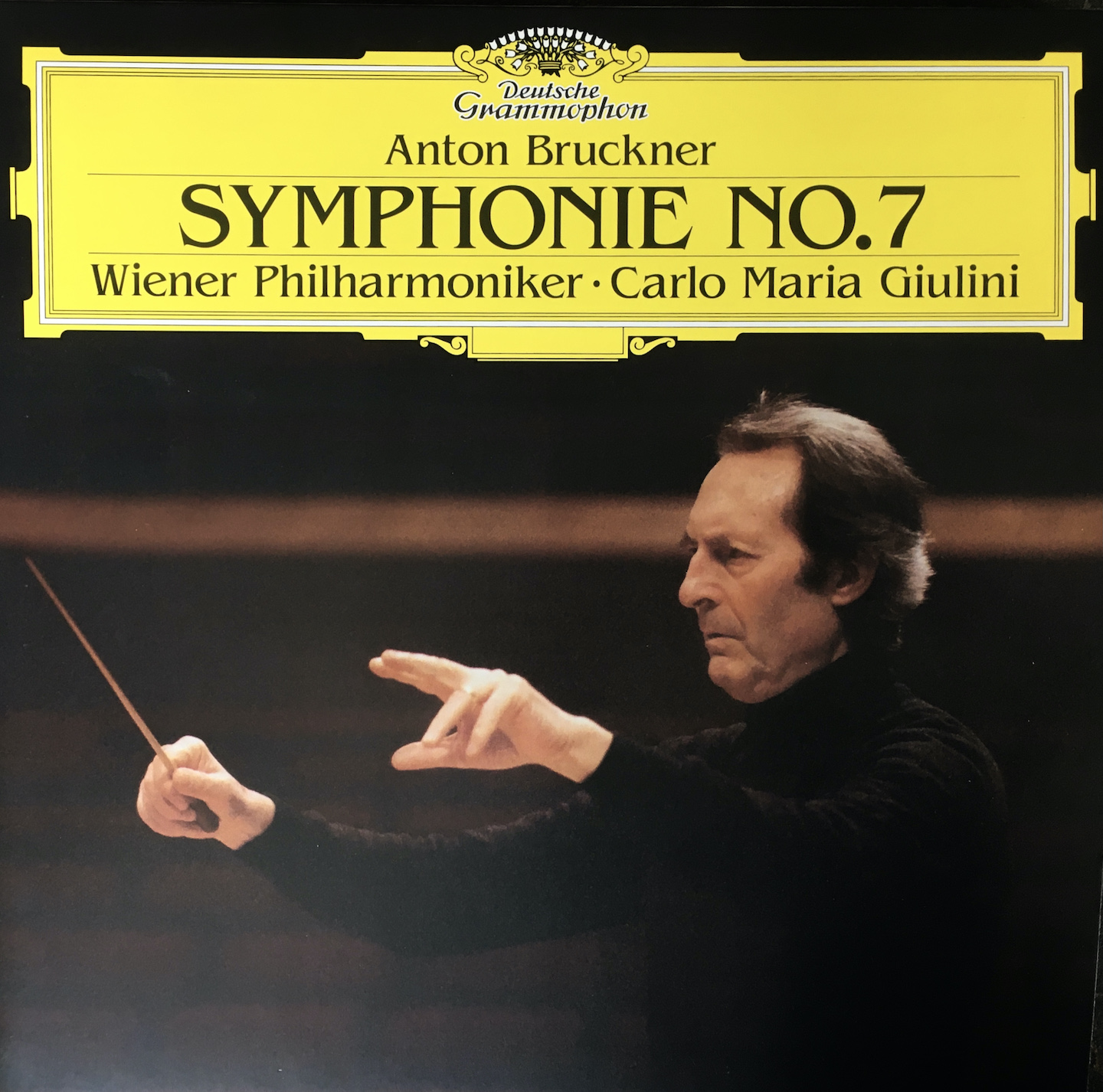

While we await the mammoth set of Herbert von Karajan’s complete cycle with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, due to be reissued in August as part of DG’s Original Source Series (mastered and cut directly from the 8-track master tapes, and from the digital masters for Symphonies 1-3), we have this essential set of Carlo Maria Giulini conducting the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra in Symphonies 7, 8 and 9 (the three most popular works, along with Symphony 4).

I say essential, and essential it is. This is glorious Bruckner conducting, playing and, yes, recording - despite being early digital. Audiophiles need not hesitate. (More on that sound and how it was achieved later).

For anyone wanting to dip their toes into the Bruckner waters I cannot think of a better place to start. Bruckner aficionados and obsessives will already know the virtues of these 1980s recordings, and can rest assured that the sonic upgrade represented on these newly remastered and cut records is worth every last penny.

Essential is a word that applies to nearly everything the great Italian conductor Carlo Maria Giulini set down on record (even his later recordings on Sony, often less than fleet of foot, have their virtues). Seasoned record collectors like myself are always on the look-out for early pressings of his legendary EMI catalogue from the 1950s and 60s. His recordings for Walter Legge with the Philharmonia are luminous, and stand in contrast to the work done by Karajan and Otto Klemperer with the same orchestra. Giulini, ever the philosopher-poet of the podium, brings his Italianate charm and grace to a diverse repertoire. His opera and choral recordings - like his Verdi Requiem and Mozart’s Don Giovanni - remain the benchmarks some 60-odd years later.

Original Release of Giulini's Recording of Mozart's Don Giovanni

Original Release of Giulini's Recording of Mozart's Don Giovanni

Moving into the 1970s, Giulini turned to less familiar repertoire - like his exquisite rendering of Dvorak’s then little-known 7th Symphony - and this is where we first hear his Bruckner in the studio. Surprisingly his choice was not one of the better-known symphonies, like No. 4, 7, 8 or 9. No, Giulini chose the obscure 2nd Symphony to record, and not even with Vienna’s primo orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic, but with the Vienna Symphony. It’s a highly regarded account, even though it incorporates extensive cuts.

Giulini moved from EMI to DG in the later 1970s, and immediately took the classical record world by storm with two superb outings with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, where he had been Principal Guest Conductor since 1969.

Giulini with Georg Solti (Principal Conductor of CSO)

Giulini with Georg Solti (Principal Conductor of CSO)

The first of these was a single record of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition coupled with Prokofiev’s “Classical: Symphony.

As a student in Rome, Giulini had attempted to orchestrate Mussorgsky’s original piano version himself: “I knew nothing of the Ravel orchestration. When I discovered it, I was amazed. There I saw that quality of intuition which only genius has.”

A 2LP box set of Mahler’s final completed symphony, the 9th - again a work which at the time was not so well-known compared to others in the cycle - similarly attracted rave reviews. As a teenager I remember seeing these advertised in the Gramophone, and immediately putting in my order at the local music shop. They both remain personal benchmarks for all three works, and both would be prime candidates for reissue in the Original Source Series. (Having said that, Speaker’s Corner did an excellent vinyl reissue of the Mahler, and OGs of the Mussorgsky are amongst the better-sounding DG LPs of the period).

It wasn’t so long after this that the legendary General Manager of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, Ernest Fleischmann, stunned the classical music world by announcing that Giulini would be the orchestra’s new Music Director. Despite its fabled lineage, the LAPhil was not considered one of the world’s “Great Orchestras”, though it was familiar to record collectors and audiophiles for its superb series of recordings for Decca with Zubin Mehta in UCLA’s acoustically fine Royce Hall. For a conductor of Giulini’s international stature to essentially up sticks and move to the music world’s boonies was thought to be - well - mad!

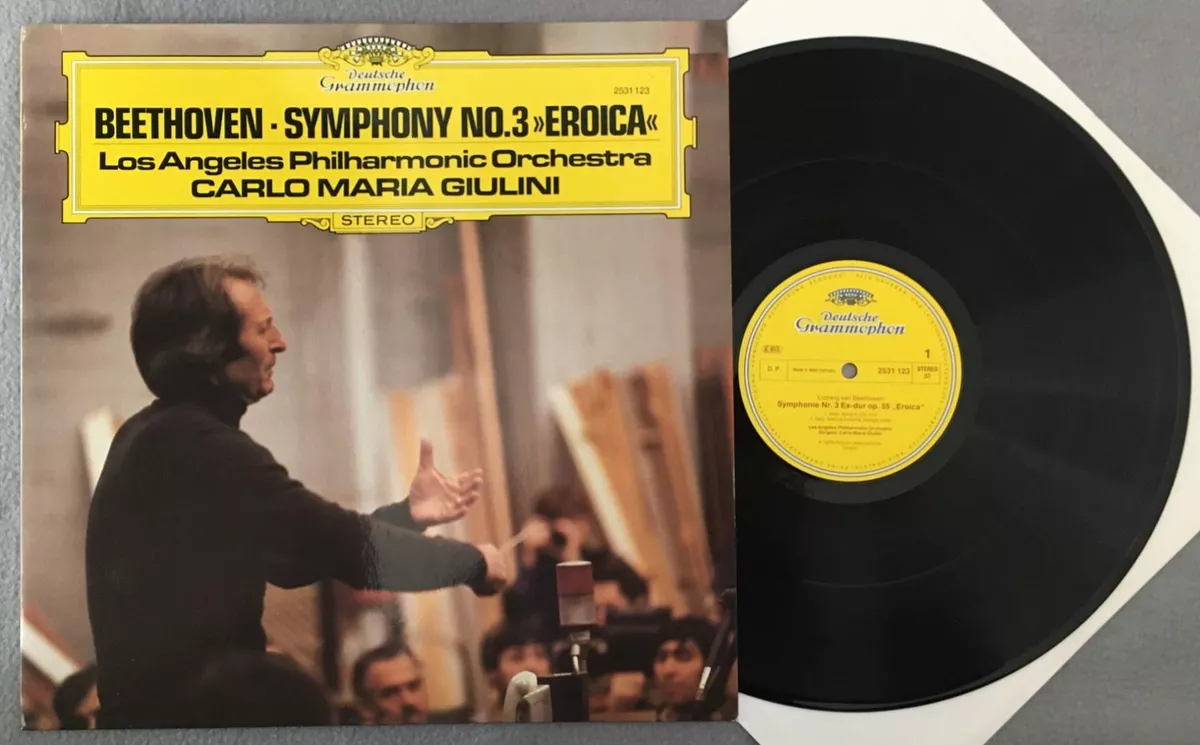

When DG released the first fruit of the new partnership, a recording of Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony, many critics thought that Giulini had fully succumbed to the heat and haze of LaLaLand. That first movement was slow in the extreme, going in completely the opposite direction of the new Historically Informed Performance specialists, or even most conductors who, like Karajan, had been approaching Beethoven more in the spirit of Toscanini that Furtwängler for half a century.

Yet for all the apparent perversity of Giulini’s slow tempi, that Eroica works, and it does so for all the reasons that make Giulini’s Bruckner so compelling. There’s a strong sense of the music’s inner pulse, and a sure and steady control of tempo on both the micro and macro levels; a facility to illuminate the many strands and instrumental textures from the inside; a keen sense of dynamics in relation to each other; an ability to make even the densest orchestral interactions sound like chamber music - you get the feeling the musicians are really listening to each other, reacting to each other both in the moment and over the larger span.

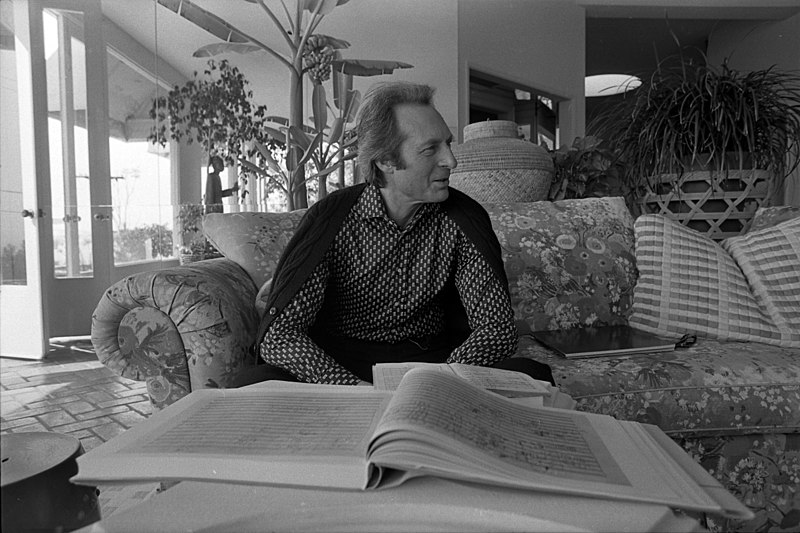

Giulini at his Los Angeles Home (Photo by Larry Bessel)

Giulini at his Los Angeles Home (Photo by Larry Bessel)

By all accounts, the musicians here in the Los Angeles Philharmonic adored Giulini. I became friends with one of them, violinist Barry Socher, in his later years, and for him no other conductor approached the Italian maestro. In conversation with music critic Tim Mangan, Sidney Weiss, who served as Giulini’s concertmaster in Los Angeles and at the Chicago Symphony, put it this way:

“Oh, it was unbelievable! Every orchestra that he conducted was absolutely in a state of musical ecstasy while he was conducting and rehearsing.”

Orchestra musicians, famously critical of conductors, felt differently about Giulini, Weiss says.

“He’s just pure music. The man is made of music and he comes before an orchestra interested in nothing but the music. He’s not looking for trouble, he’s not looking for who’s not playing well, or who might be sabotaging, that sort of thing. There’s nothing on his mind but the music, and he’s so inspiring that the impact is enormous.”

I myself heard Giulini conduct in person only once, in the early 1980s, at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in one of his signature works, Verdi’s Falstaff (later given a superb recording in Los Angeles). Throughout all the hustle and bustle of the comedy, the music seemed lit with an Autumnal glow from within, like a gorgeous Renaissance illuminated manuscript. In the grand finale, after all the mistaken identities and mischief-making are revealed, the entire cast comes together in a musical fugue. Falstaff, now fully aware that the joke has been on him all along, leads this final celebration of the ridiculousness of life, singing: “"Everything in the world is a jest ... but he laughs well who laughs the final laugh”. The effect in Giulini’s hands was transcendent, one of the most life-affirming moments I have experienced in any theatre or concert hall.

Two characteristics define Giulini's music-making. One, he always gives the impression that he has thought long and hard about the composer’s intent beyond the mere detail of the score (which he has clearly studied and absorbed over a prolonged period of time), and that he feels it is his job to present the narrative of the score, and this deeper intent, in a manner that the listener will fully grasp. Two, Giulini believes the music should always sound beautiful - not just in a superficial way that may run contradictory to the works’s deeper intent - but in a way that communicates what the music is, at its heart. He is intent on truth, not show. He seeks the heart beating beneath the notes. He is both a thinker and an aesthete - hence the philosopher-poet of the podium.

During his student years in Rome, Giulini was invited to join the viola section of the fabled Augusteo Orchestra (later renamed the Santa Cecilia Orchestra), where he remained for ten years, playing under many of the world’s greatest conductors, including Victor de Sabata, Erich Kleiber, Otto Klemperer, Richard Strauss, and Bruno Walter. Walter made a particularly strong impression: “I came to the end of a performance of Brahms’s 1st Symphony and, even from the last desk of the violas, I felt I had been playing a solo concerto! I was no longer part of a mechanism. Under Walter I felt I was a musician who was being invited to make music with other musicians.”

The Augusteo Orchestra (later the Santa Cecilia Orchestra) in 1926

The Augusteo Orchestra (later the Santa Cecilia Orchestra) in 1926

This early experience not just as an orchestral musician, but as a violist playing the inner lines of the orchestral texture, influenced and shaped Giulini’s approach as a conductor. In conversation with music critic Richard Osborne, Giulini stated:

“Perhaps because I am a viola player, I think the inside string parts are of great importance where the music’s ‘plastic’ quality is concerned. Other instruments give you the music’s physiognomy, but it is the inside parts which provide the bones, the inner structure.”

Giulini rehearsing with the strings of the LA Philharmonic

Giulini rehearsing with the strings of the LA Philharmonic

Osborne also quotes Simon Rattle concurring on this matter (Rattle was Giulini’s assistant in Los Angeles in the early 1980s): “Giulini’s orchestral parts were marked in more exact detail than any I have ever come across. And because of the way he divided up the bowings, and because he knew physically how string players create their sound, all his arms had to do was show the manner in which they should make those motions.”

All of this is highly relevant to anyone approaching the scores of Bruckner, which are all about inner lines and shifting textures.

Bruckner (like Giulini) was a devout Catholic, whose music was intended to express and illuminate his faith.

“They want me to write differently,” he once wrote. “Certainly I could, but I must not. God has chosen me from thousands and given me, of all people, this talent. It is to Him that I must give account. How then would I stand there before Almighty God, if I followed the others and not Him?”

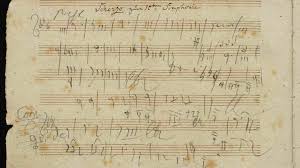

This does not mean Bruckner’s music is “religious” (though his principal work beyond the symphonies were his Masses, Motets, and the Te Deum), but it does mean that it has a mission, a sense of almost sacred purpose that somewhat sets it apart from the symphonies of his contemporaries, and of its primary model, the symphonies of Beethoven, primarily the 9th. Beethoven was not a religious person, a “man of faith” in any traditional sense (though he was a man of spiritual conviction). Rather he was the arch-humanist, struggling with everything he found in the world, and in himself: his deafness, his irascibility, his sense of isolation, his constantly thwarted desire for a deep emotional connection, for love, that eluded him. He is engaged in a struggle with life, and a struggle with music itself, as his notebooks attest. Not for him the seemingly effortless inspiration of Mozart; with Beethoven it was a constant struggle to articulate, develop and make coherent the musical ideas running around in his head.

Page of Beethoven's Sketchbook for 10th Symphony (1825)

Page of Beethoven's Sketchbook for 10th Symphony (1825)

Beethoven’s final, sublime symphonic statement - the 9th Symphony - was the work to which Bruckner aspired his entire compositional life. As a young man working as an organist in the provinces (he was the organist at the monastery of St. Florian for many years), he urged friends in Vienna to let him know when there was to be a performance of “the Ninth” so he could travel to attend it, no matter what the weather. Finally the opportunity came in 1866 (when the composer was 42), and the experience clearly influenced Bruckner’s revision of what would become his Symphony No. 0 (“Die Nullte”). As Peter Branscombe puts it in his excellent sleeve notes for this reissue of Giulini’s Bruckner 9th: “the tonal uncertainty, stabbing thematic fragments, potential for drama and large-scale conflict are all features that recur particularly in the opening movements of later Bruckner symphonies.”

Like Beethoven, Bruckner struggled too with his compositions, and his many revisions before and after a work’s first performance have contributed to the many variations seen in different editions of his symphonies. I will not be getting into the thick weeds of competing editions of the scores - this is territory for those more deeply imbedded in the Bruckner universe than I. For these DG recordings Giulini adopts the Nowak editions.

Bruckner not only struggled to write his music. His challenges in getting it performed at all, let alone decently, were legion throughout his life. Researching this article I came across this choice 1886 quote from a critic in the German Times of Vienna, included in the splendid tome Lexicon of Musical Invective: Critical Assaults on Composers Since Beethoven's Time (1965) by Nicolas Slonimsky

“We recoil in horror before this rotting odour which rushes into our nostrils from the disharmonies of this putrefactive counterpoint. His imagination is so incurably sick and warped that anything like regularity in chord progressions and period structure simply do not exist for him. Bruckner composes like a drunkard!”

My own first exposure to Bruckner’s music was singing some of the Motets in our chapel choir. This was music utterly different from anything else I had hitherto listened to, played or sung (and we sang everything in our choirs, from Medieval and Renaissance polyphony to Victorian sacred music, from Verdi and Brahms to Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast and Honegger’s King David). What struck me most was how you would be singing a line in a certain tonality or harmony, and suddenly the chord and harmony would shift in a way that was completely unexpected, and often ravishing. You had to get the tuning dead right or the effect of almost spiritual awe would be lost (and since this was mostly unaccompanied part-singing, the tuning could be tricky).

That sense of harmonic flux, of unexpected tonal shifts, provides many moments of rapture in the symphonies. Other qualities you will notice are a layering of the orchestra, almost dividing strings, wind and brass into separate choirs playing off each other in an antiphonal manner reminiscent of the choirs of voices and instruments set on the opposing sides of St. Mark’s Basilica in the Renaissance music of Giovanni Gabrieli. One of the principal challenges of any performance of Bruckner’s symphonies is finding a way to make sure one instrumental group (especially the brass) does not overwhelm the others. In addition the episodic nature of much of the writing needs not only to have its own character but also be integrated within the overall musical argument. Otherwise there will be too much of a sense of stop-go to the performance.

Giulini’s special gifts as a conductor are immediately apparent in his rendering of the 7th Symphony. The long, winding, tonally ambiguous opening phrase emerges (as do so many of Bruckner’s opening phrases) out of a silence giving way to a shimmering haze of trembling strings - a deliberate call-back to the opening of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. Giulini shapes all of this to perfection, immediately establishing a forward momentum and sense of purpose that accommodates every seeming digression in the musical argument without ever coming to a standstill. The entire movement proceeds as if sung in one breath.

This symphony is probably the most popular of the cycle, in large measure due to its comparative softness, an almost pastoral, idyllic quality that speaks in part to Bruckner’s love of the Austrian countryside. Like Mahler’s 4th Symphony, there is a tenderness that pervades the score, with histrionics kept relatively at bay. The work was written under the looming shadow of Richard Wagner’s impending death, and indeed word of Wagner’s passing arrived as Bruckner was penning the exquisite slow movement - which became in its final bars a musical eulogy.

Wagner's Funeral Procession in Bayreuth, 1883

Wagner's Funeral Procession in Bayreuth, 1883

Bruckner had met the older composer in 1965, and also attended the first complete performance of the Ring at Bayreuth in 1876. Needless to say, next to Beethoven, Wagner was one of the major influences on Bruckner’s own music. The 7th Symphony (1881-83) is full of Wagnerian overtones. The very end in particular has the Gods’ Ascent into Valhalla at the end of Das Rheingold written all over it.

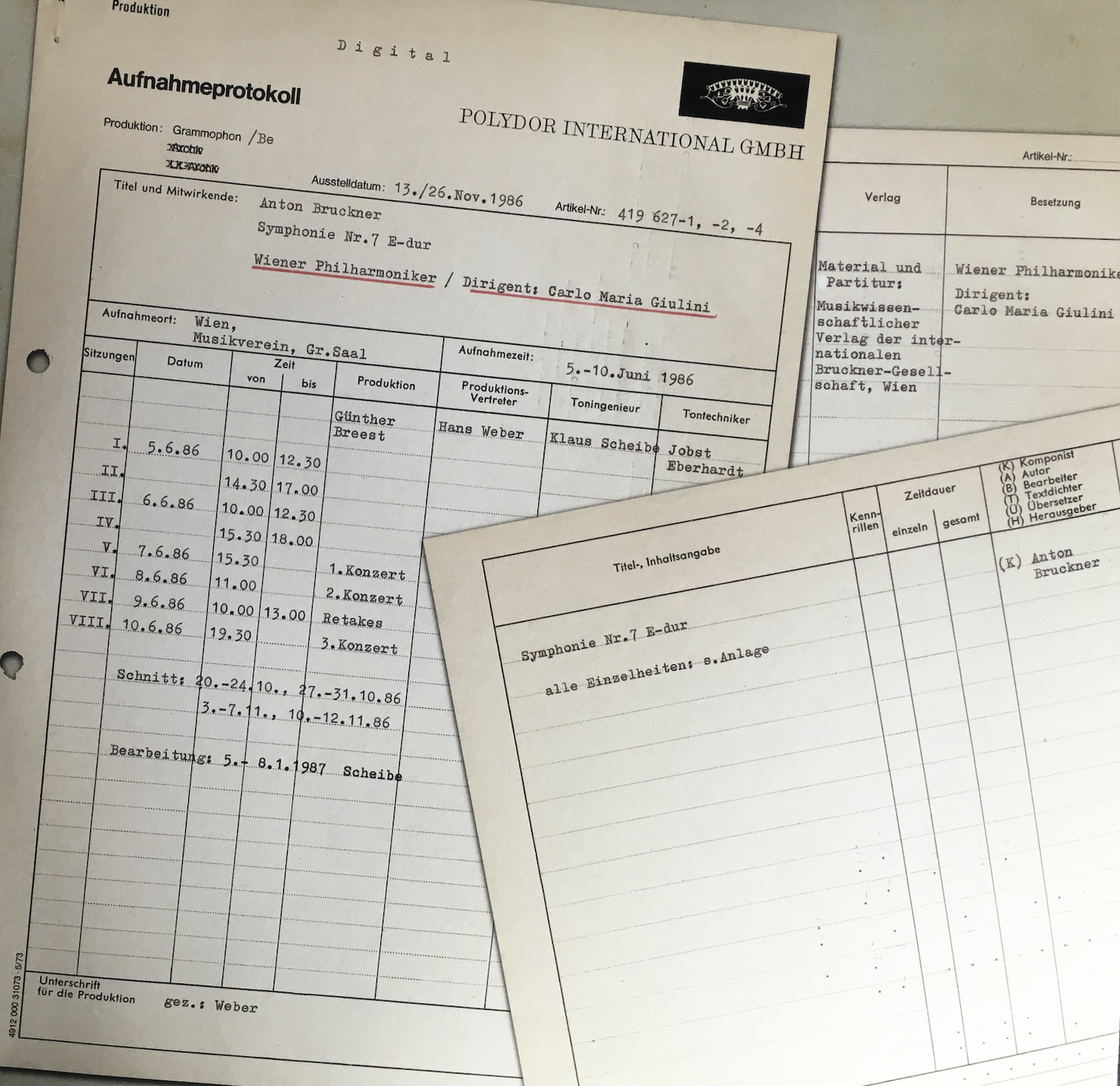

Part of the new Symphony 7 gatefold, showing original recording documentation

Part of the new Symphony 7 gatefold, showing original recording documentation

The symphony fits Giulini’s sensibility to a “T”, and his way with it, while not shortchanging the massive climaxes, is full of sunshine, pastoral idyll, tenderness and soft (and occasionally louder) lamentation. It is a reading of great tenderness. The orchestral sound is beautifully blended, and the many solo passages for solo woodwind and brass instruments are exquisitely rendered by the Vienna Philharmonic’s storied players. There is that tell-tale VPO sweetness in the string sound. When the brass really kick in, man do they throw a punch, but there is always a sense that they are coming from within the orchestra, not overwhelming it (which I felt was a tendency in the recent Original Source reissue of Barenboim conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in Bruckner’s 4th Symphony).

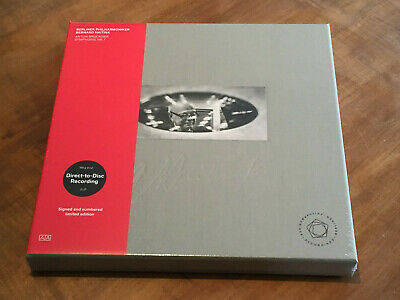

In its latest vinyl incarnation, you might be hard pressed to believe the original recording by Klaus Scheibe in the Musikverein was digital. I was drawn in immediately by the organic, sweet sound, and only in some places did I sense a bit of an edge to the violins, or the lack of three-dimensionality, or indeed the lack of the many analogue verities. What the recording lacks in these regards was only immediately apparent when I put on the EBS team’s Direct-to-Disc recording of Bernard Haitink conducting the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in the Berlin Philharmonie in his farewell concert with the orchestra.

This recording is a marvel on every level, with you practically on the conductor’s podium, hearing every detail, every nuance. Though what you do not get is the blend afforded in the Giulini by the Musikverein itself, one of the greatest concert hall acoustics in the world, and the perfect space for Bruckner’s music to unfold within. The sound of the Berlin Philharmonie is quite dry and clinical in comparison, though no less thrilling for that.

That Haitink/BPO D2D is in a class of its own, and will cost you a pretty penny to acquire. But maybe in some ways I prefer the Giulini performance. It humanizes Bruckner in a way that is touching and endearing, it brings Giulini’s Italianate grace to bear on the rugged Austrian’s crags and cornices. There are moments when I thought I was listening to Mozart or Schubert rather than Bruckner. As such, it is irresistible. It is definitely a great introduction for the Bruckner newbie - as is this whole set.

(If you want Haitink’s fine 7th interpretation in a more affordable form, go for his first Concertgebouw recording from the 1960s on Philips, a demonstration analogue recording in its own right).

In Part 2 I will continue my review of this set with Symphonies 8 and 9. Plus an interview with Rainer Maillard at Emil Berliner Studios talking about the original recording team for these sessions, their methodologies, and how he and Sidney Meyer went about improving the sound for this new vinyl release.