Records Pressed in Iceland From Sugar Beets Not PVC is Larry Jaffee's and Kevin DaCosta's Sweet Dream

Is the Thermal Beets Record Pressing Plant A Sustainable Concept?

(The lead photo shows Kevin, Larry and Gummi in the Grindavik lava field about 10 miles from the Keflavik International Airport, near where they are planning to build a pressing plant. The volcano erupted two days after we left in March and throughout the fall).

Blondie released its fourth album Eat to the Beat in 1979. No way then could the band have known that nearly a half-century later it might be possible to press beats onto records made of beets that, at least theoretically, one could actually eat!

Thermal Beets Records is a partnership founded by Larry Jaffee, the author of Record Store Day: The Most Improbable Comeback of the 21st Century and co-founder of the Making Vinyl conference, and Kevin DaCosta, a vinyl manufacturing consultant and the technical director for Evolution Music.

The two began discussing in 2023 how best to combine their interests in music, environmental friendliness and records, by pressing them not from PVC, but rather from that certain vegetative plant—the red variety better known for borscht, the white one for sugar extraction.

The partners solidified their plans and expanded the project to include two additional co-founders: Gudmundur (Gummi) Isfeld and Jónbjörn (JB) Birgisson.

The star at the center of this project is Evovinyl™, an environmentally friendly sugar beet based material that Evolution Music has been developing for the past five years and that will be marketed as a long-term replacement for vinyl. In the following interview, Larry and Kevin share the ways that they came up with the idea of launching a pressing plant in Iceland, why Iceland is the best country to embark on this adventure, and how their new product can potentially be used to shape the future of record manufacturing as we know it.

Together, they share the story of Thermal Beets and how music, technology, and sustainability created opportunities at the crossroads of creativity and innovation.

Evan Toth: It's great to have both of you here to talk about Thermal Beets. I'd met Larry before, but I met Kevin a year and a half ago in Haarlem at the Making Vinyl conference and at the Haarlem Vinyl Festival. Tell me, how did we get to Iceland and vinyl? I guess it started there at that very meeting.

Larry Jaffee: Actually, it even started just a little bit earlier because in October 2022, I was flying back from Amsterdam after Making Vinyl in Germany and I had to go through Iceland. I was knocked out by the in-flight entertainment. At that October 22 event, it was the first time I heard something about a plant-based material, and Marc Carey was on the sustainability panel. Marc and I met at that point.

Even at that point, I wasn't thinking, "Oh, I'm going to do something entrepreneurial with this." It sounded like a really cool idea, and it was a good solution to the product search that was going on. Something different from the PVC process. Kevin, were you in that, at Offenbach? At that one.

Kevin DaCosta: Yes, yes.

lj: I don't think you and I really talked about that, at least.

kd: Not about that. No, no, no.

lj: Yes. What happened was about five, six months later, when we were at Minneapolis, I was moderating a session on the international pressing scene, and Gudmundur Isfeld from RPM Records in Copenhagen was on it. Right before we were about to start, I'm looking at his bio and it says he was born in Iceland, and I said to him, "Did you ever think about doing a factory in Iceland?" He said, "I already manufactured at least a third of the records that are being sold there." Then we went into the session. Then--

ezt: It was just like a little tidbit.

lj: I had to wait another four or five months, and in Haarlem, where you were, I finally cornered Kevin and I said to him, "What do you think about doing a factory in Iceland?"

ezt: Kevin, now one of the things that you do is, from what I understand, and you can help me figure this out now, but you help people figure out the logistics around putting together a vinyl pressing plant. Is that right? Why don't you tell us exactly what you do?

kd: Thanks, Evan. I'm an engineer by trade and about eight years ago, thereabouts, when I was seeing the massive revival of vinyl, I'm someone who's always bought vinyl and completely obsessed by, and love records and music. I was tracking the growth of the market, and I started to read about there being a bit of a bottleneck as a result of not being any new presses available. People started buying records again, but there were no presses to build the capacity that was needed.

Long story short, I ended up reaching out to a Canadian company called Vinyl Technology that had just started, and ended up inviting me over there and working with them on site. They ended up saying, "Well, you'd be the European guy for us." I ended up first working exclusively for vinyl, installing and providing technical support to the vinyl customers. Because I was a self-employed contractor, people started getting in touch with me and saying, "Oh, we're building a factory as well. Could you help us with that one, but it's a different press? It's a Pheenix Alpha, a new built or whatever it is."

I started to help with those and ended up getting lots of experience with all of the other presses as well. I still work with all those different presses and companies now. I've just found myself in a fairly unique position, just I didn't really have a plan, but it worked out like this. More and more people have started to develop their own factories in different parts of the world. I'm not on social media or anything. I'm just on LinkedIn and people reached out and said, "Can you help me with this." It's led me to installing and pressing records and teaching people how to use a press through to designing the infrastructure and looking at the business aspects of it with certain companies. It's because what we've seen, and you might know this yourself, is scroll back 10 years and there was less than 40 or 50 record factories left in the whole world. I think it was as low as 35 at one point in the whole world. Fast forward this last 6, 7, 8 years, there's now around 200, and nearly all of them are small to medium-scale factories, 1 to 6 presses.

They tend to specialize in independent music. They tend to have a high frequency of jobs, but low volume, 500 to 1,000 is very typical. They tend to be really highly committed, very passionate people that have a particular passion for music. Maybe they've come from some other aspect of the music industry, maybe a label or maybe even an artist sometimes, not necessarily manufacturing or they don't necessarily come with technical engineering type background or skills.

I've ended up finding myself in a very lucky position of helping people to see how the cake is baked and to hopefully develop efficient manufacturing systems because I'm able to put into what I do, my history of working in the renewable sector with companies like Tesla and the solar sector. Infusing what I try to do, and this is where myself and Larry align and where we come together with Iceland. The Iceland product is trying to inform both the manufacturing process itself with every aspect of sustainable best practices we can possibly muster along with the product itself.

Because we found - and where we align again - is that a lot of the music industry is very much inclined towards trying to be more sustainable, but don't necessarily know the detail of how we get there on the ground level, not just in terms of saying nice words about it wouldn't be great if we could reduce our carbon footprint, but how do we actually do that? That was the basis in which me and Larry put our heads together and thought, what would be the gold standard, and where can we put it? Iceland is the answer.

Kevin and Gummi talking to the president of the Iceland Eco-Business Park (with his back turned to the camera) at the construction site (photo by Larry Jaffee)

Kevin and Gummi talking to the president of the Iceland Eco-Business Park (with his back turned to the camera) at the construction site (photo by Larry Jaffee)

lj: I said to you, "What do you think about doing a factory in Iceland? Do you remember exactly what you said?"

kd: Actually, credit to Making Vinyl conference because the journey from the UK to the US, because I've been to a bunch of, I'm making my own companies now. The cheaper flights tend to go via Iceland. I just thought, you know what I'm going to do? Instead of stopping for one hour at Reykjavik and then bouncing onto the US, I'm going to go the day before. I'd heard about these great record stores in Reykjavik. I thought if I take the same journey, the same way, but go the day before, I can have 24 hours in Reykjavik, raid all the record shops, do a spa at the pool, and be on the plane the next day.

That's what I've done and found these amazing record stores. Also, I've been someone who's been loving Icelandic or artists from Iceland for a long time. Then when you're there, you go into pretty much any random bar, and it's a band playing. Iceland is one of those countries that pound for pound really punches above its weight in terms of its musical output compared to its tiny population.

Larry's been a fan of a lot of the music there, so again, we vibed on that, and we're like, "This is a really unique place." The icing on the cake is just how progressive the country is in wanting to actively get behind initiatives around sustainable businesses and manufacturing, and efforts. It's like the perfect ground zero for trying to design and implement the most sustainable factory on the planet, if possible. The reason it's possible is because actually half the work is done for us because the whole country, 97% of all of the power used in Iceland comes from geothermal and hydroelectric sources, so it's all green energy. Even if you tried to create a carbon footprint, it's harder than most places when you're in Iceland because it's all set up for it. We got the conversion of a perfect set of circumstances, an incredible music ecosystem and activity, a very supportive set of partners in Iceland, both from a music and label perspective, but also from a government and business perspective, and we've also got the insights that we've gained over the last few years in terms of how to optimize the manufacturing process for quality, efficiency and importantly, sustainability.

ezt: Back to your comment about the music. I just wanted to say thanks also for the record. I believe this is the first record that you guys pressed at the new plant. We're really here to talk about the plant and pressing in Iceland and everything, but the music is so excellent. Of course, listeners should know there's definitely a Björk vibe here, but it's so much more. There's some great writing, great production, and it really comes through here.

Larry, isn't there a funny story about you hearing you were on an Icelandic airline and you heard the -- Or how did that go? You learned about the music there, too.

lj: I wanted to point out that, Kevin, I wasn't as well versed in Icelandic music as he was. I basically knew the Sugarcubes, Björk and Sigur Rós. That was where it ended, but when I was on the flight, I was knocked out by the in-flight entertainment, and I was like, "There's 200 artists here and I don't know any of them. If any place in the world needs a record factory, it might be Iceland." I do want to just, and Kevin can add to this, clarify one thing. We didn't press that record that you have at our factory. Kevin, you want to talk a little bit about that just a little bit?

kd: Yes, the factory doesn't actually exist yet, just to be clear. We're working on it as we speak, in the sense that we're pulling together the investment, the partners, and the specific factory space, and everything. That's what we are working at as long as we bring together the partners and investors that we're working on right now, and that all comes together. We aim to be open by the end of 2025, best case scenario, worst case early, 2026. Takes a little while to get everything together.

What that record represents is the process we're going to demonstrate is possible. The use of fully sustainable materials, 100% organic, plant-based material instead of PVC, sustainable packaging. There's even an extra digital element to it which we're calling smart vinyl, which is like a download card on steroids, let's say. It's like a digital treasure chest with all sorts of free content, but it's interactive, meaning you can communicate with the label and the artist directly through it and have that two-way engagement. It's about fan engagement.

Really, the reason we wanted to do a record as an example of what Thermal Beets represents, is to show what is possible. That we can make records much more sustainable, and we can engage the listener, the fan, the community at a much deeper level so we can have and enjoy, and love our records in the way that we already do, but we can have an extra layer to that and we can innovate.

What we're hoping to show with Thermal Beets in Iceland is just what is now possible in terms of trying to be the gold standard for both sustainable practices in the record industry, but also innovation. There's a lot more we can do with a format that we love and will love forever, but it's been around for 70 years. We're certainly not trying to reinvent the wheel. We're just trying to make a better world.

ezt: This one that I have, this is that formula of, what it is?

kd: Yes, it's made from sugar beet.

ezt: I could take a bite out of this right now and I'd be fine?

kd: You could, and it won't kill you. That's the point. Look, I just want to say something about PVC. Look, you can see--

ezt: When Larry saw me at the 'FMU Record Fair, actually, I was munching on one of these in the corner. The food was so expensive there that I just decided to start eating the beets records.

kd: You know what? When it's fresh off the press, literally, as you make the record, for about an hour or two before it totally cools down, it smells like burnt caramelized sugar. It smells like burnt candy.

ezt: It's got a smell, doesn't it?

kd: It just lingers there a little bit, right?

ezt: I think so. Am I crazy? Larry, am I crazy here?

kd: No.

lj: Actually, I have not smelled it. We don't have one right here, but I trust you on this.

ezt: Larry, as two academics here, we've finally gotten to the place where we're smelling records. This is the height of vinyl and sound scholarship right here.

lj: It is important to talk about one of the other founding partner of the trio, and then we've since have added a fourth, an Icelander. Guðmundur, who Kevin said, "You mean Gummi," said this. He's the co-owner of RPM Records in Copenhagen. He said to me, "I've thought about doing a factory." When we had that first Zoom meeting, the three of us, we realized we were all on the same wavelength on a lot of this. That one was pressed on vinyl in England. The next one will be done in Copenhagen.

ezt: Tell me a little bit about the history of the sugar beet as being a PVC substitute. Where did this idea come from? I imagine it may have been used somewhere else in manufacturing before vinyl. Who was the person that said, "Hey, you know what we could use this for?"

kd: Just a quick question. It was actually that sampler, the Iceland Airwaves sampler, was pressed at Vinyl Presents in the UK.

lj: Oh, thanks for pointing that out.

kd: No worries at all. In terms of how we came to sugar beet for this, the company Evolution Music in the UK was founded by three guys, Adrian, Steve and Marc Carey, we've mentioned the CEO, a few years ago; five or six years ago, something like that. It's taken them a few years of research to get to the point where we have a viable feedstock in terms of the raw material. I've been the technical director for a couple of years now. They invited me to join as a technical guy a couple of years ago.

They were working on this before I got there. They had tried all sorts of different materials. There wasn't really something they could refer to as a ground zero that they took the idea and evolved. They literally evolved it from nothing to base it on. We tried things like hemp, we tried all types of fungi and different organic materials. Hemp worked a little bit, but it's a bit too fibrous. Fungi was hilariously disintegrated and didn't really work to try and make it into a polymer first before you compound, but sugar beet was really, really robust. Mechanically speaking, it walked out of the gates.

Now, what we've been doing since we first figured out it worked, and I came in, I had entered the stage at that point when they first got it to work mechanically, it's really been improving its mechanical qualities whilst also improving its sound. We've still got some work to do. It's not quite there yet and we're still saying it's proof of concept, but as you know yourself, because you've got a copy, if no one told you it was made from something different, you wouldn't necessarily know.

Now, there is a noise floor that's higher than PVC a little bit. If you turn it up high, you'll notice maybe in the quiet moments, but not so much that it would disturb the music. We're already at a point where we've proven its viability as a potential alternative to PVC, but we're working to make sure that it's not only as good as, but better ultimately, both in terms of quality of sound, but also in terms of cost. Because the other thing about sugar beet is it's actually quite a cheap material to produce, and pound for pound, much cheaper to produce and make into records than oil derived PVC. It's also fully nontoxic.

One of the ideas we were keen to use Iceland as ground zero for, is to develop this idea of farm to factory, to fan. What happens with PVC right now is it creates a carbon footprint in multiple ways. First, you start with oil. That comes from, let's say the Middle East. Then it's shipped to another part of the world to be processed into a basic resin. Then that resin is shipped somewhere else to be processed into a final compound. Then it's shipped to the factory wherever in the world to be made in the record.

There's two, three or sometimes four shippings that happen at the various stages of the material. That's, of course, creating a compound before it's even made into a record. What can be different about utilizing something that any continent can grow, and that's an important point to make. One of the things about sugar beet is it's very, very hardy and can grow in any environment, meaning hot climates, cold climates, and everything in between.

Which means the processing from taking it out of the earth to its initial residence stage and then onto the final compound, there's of course work to do, but it's much more simpler than it is to take oil and do the same process. What that means is you can micro-size the production from farm to factory, which means that you can end up in a scenario where you could actually have those production facilities leading agriculture to manufacturing in each landmass.

Why do we want to do that? It's because we want to have our cake and eat it. We want to make a product that's more sustainable by its very nature in terms of its material. We also would like to cut out these phenomena of globally shipping things, creating a carbon footprint around the world. Wouldn't it be better to set up local production in each landmass, have it made in that landmass, shipped across the ground to the factory, and made and distributed in that landmass? That would be the holy grail.

We have that opportunity to develop that working model of farm to factory to fan in Iceland, which is another beautiful thing about the country and how open they've been to working with us.

ezt: I imagine that would also keep the cost down of the product. It might make it more attractive than your regular PVC product, maybe?

kd: Yes. Again, I don't want to hate on PVC because, as you can see, our wall of records is not quite as impressive.

ezt: I've got some too.

kd: [chuckles] Because there is an argument, I think a legitimate argument to say that your traditional PVC record, if it ain't broke, don't fix it. How many records honestly end up in the landfill? They don't really. They tend to be re-gifted and sold, and passed on, and inherited. You can qualify it, but it's not so much the end product ending in the ground, which PVC by way is toxic to the earth in a way that sugar beets and this plant alternative is not toxic to the earth. If you did eat it, you're not going to get ill. You'll survive.

It's also the manufacturing process to get to a record is quite destructive in that sense. We do think we have an alternative, but of course, this is the high-risk bit. The high-risk bit is if we don't get to that holy grail of equal to or better than PVC in terms of sound quality, then we almost have nothing. It will be an interesting novelty and footnote of history that we had to go, and we didn't quite get there.

In terms of cost, though, ultimately, right now, it's more expensive than PVC to make records because we're making it in the laboratory. As soon as we can get to a point where we can justify going to a production line, the economies of scale that we can enjoy will bring us price parity with PVC in the first year or two, and then ultimately, it'll be cheaper because as a feedstock, as a raw material, as I say, sugar beets is much more cost-effective than oil derived anything, including PVC. That's really a scaling issue.

Our job is to grow the demand for records made from this material to the point we can start to enjoy those economies of scale.

lj: Yes. In terms of the sound, an Abbey Road in-house producer named Rob Cass was speechless to find out that the test record he heard was made entirely from plants, was speechless that it was not a PVC record. He played it for Peter Thomas, who makes the monitors for recording studios. He said it was also indistinguishable from traditional vinyl and felt so strongly about it that he invested in Evolution Music. They've already achieved a pretty high level of audio fidelity, but Kevin knows better that it can be even improved further.

The other thing about this project that is, I think I find where the potential is, it'll be like artist-driven. For example, Billie Eilish has made a big priority of her last record being as green as she thought it could be. We're hoping that she'll consider Thermal Beets next time around. It's the same thing true with the Coldplay record that came out a few months ago. It's certainly a good thing that they recycled these plastic bottles that were discarded into a river in South America. On the other hand, it still came from a fossil fuel originally.

ezt: Is that what they're doing, Larry? Because I just got a record, in fact, this week that they were calling it Eco Mix. Now, I imagine that a lot of the different recycled things probably are recycled from different things, but typically for our audience here, people should know it's common practice in a record pressing plant to say, "Take some of the vinyl that was discarded for some reason," and then they reuse it. In fact, it's often said that the best-sounding mix of vinyl is often a mix of virgin PVC and recycled PVC together. Kind of gets you a special, particularly good mix.

You mentioned these plastic bottles with Coldplay. What else do you know as-- Now you're doing something totally, we're talking about using organic matter, which I suppose you could argue oil is organic, but that's for another time. You're talking about using a vegetative matter here to create a record. What other things are people experimenting that you've heard of as far as making vinyl greener?

lj: Well, there's already a product on the market called BioVinyl, that it's a mixture. Any discussion about this type of thing veers into the territory of potentially greenwashing. There are claims made that have not really been substantiated fully. We were very mindful of that. Once we start doing our own marketing, we're going to stick to the science, essentially. You know what I mean? Kevin can really speak better to that.

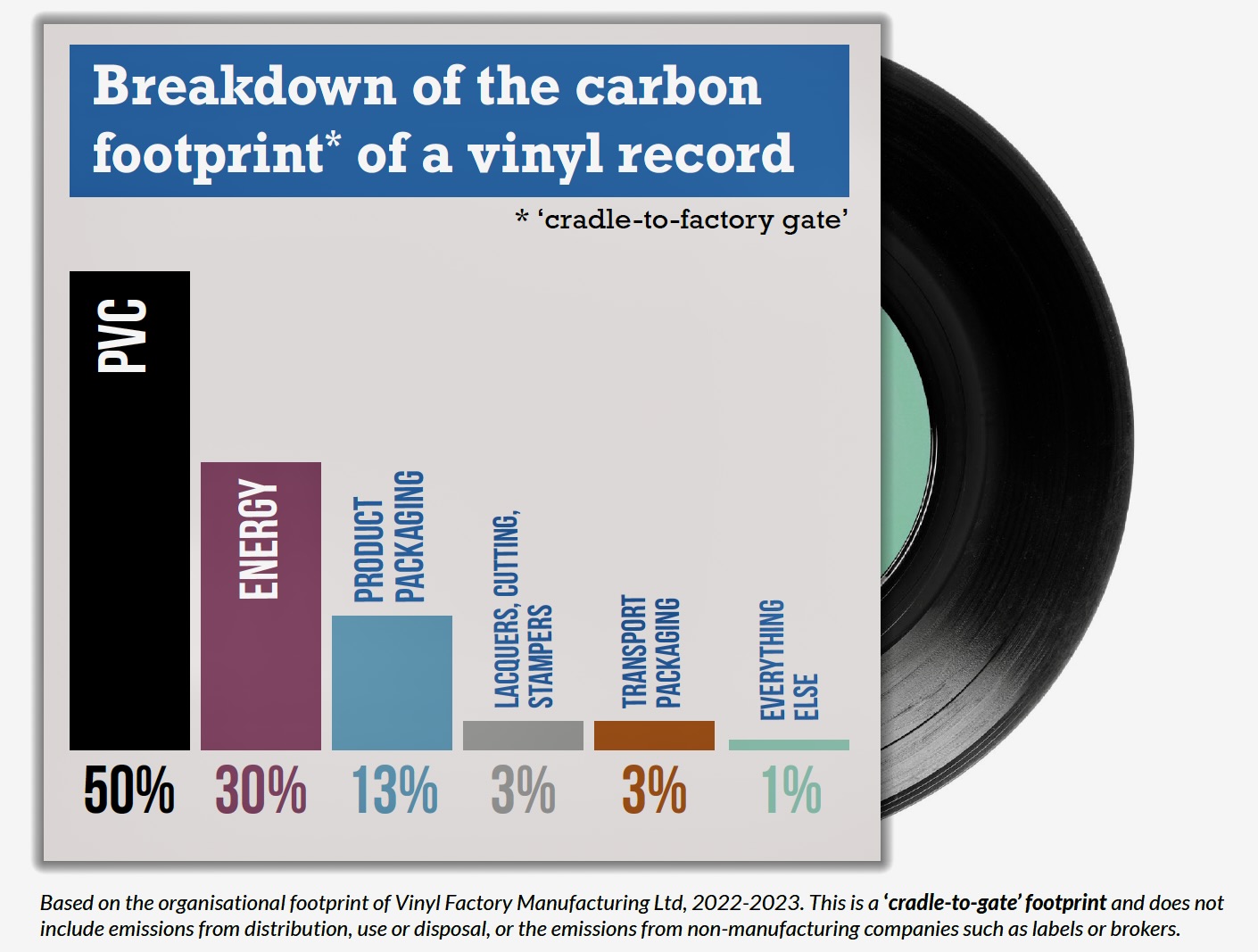

lj: The other thing about that is the Vinyl Record Manufacturers Association put out an excellent report. Well, they put out two reports. One about the carbon footprint of a vinyl record. What Kevin was talking about before about the circular economy, if we eliminate the shipping-- For example, that last batch of a taste of Iceland records was shipped by air to Iceland. That's a substantial lowering of the carbon footprint.

As far as once we can get certified, we'll be able to show that because the record is made of a plant-based material, the carbon footprint is not being left by that physical object, unlike even BioVinyl, because we know that some portion of it did come from recycled cooking oil.

ezt: Instead of smelling like beets, they smell like old French fries.

kd: Something like that.

kd: Yes. The term BioVinyl that seems to have permeated the industry in the last couple of years is, I get that is shorthand to indicate that this is better than traditional PVC in terms of its carbon impact. In some ways, it's arguably more unhelpful than it is helpful because right now, BioVinyl, it's become almost a meaningless term in that it can include everything from just recycled PVC, to records made from vegetable oil of which you don't necessarily know the mix, the proportion of mix, what other ingredients got in it, and what is the provenance of that oil.

Obviously, if it's recycled oil, it infers that that oil has been processed once and then again, so that's two processes, two carbon footprints, and everything in between. There's a range of things that BioVinyl could apply itself to do. Even there's been records made from recycled plastic bottles from the sea, for example. They don't sound great, but it is possible to take different sources of plastic and recycle it into something that you can then term as better than virgin PVC in terms of if you look at it from a certain angle.

As Larry mentioned, one of the challenges here is it's very difficult, in fact, to really be exact about some of the provenance of these materials and to capture precisely what the carbon footprint is. Whereas the very cleanest way of doing it, and forgive me for suggesting this about the evolution plant material here, but the advantage is you can identify every single stage of the process and you can calculate, which is what we're in the middle of doing, calculate the impact of each of the processes.

If you have a material that is essentially a combination of different bit of vegetable oil, well, what vegetable? There's a difference. It's one difference. Palm oil, for example, is a vegetable oil, but it's not particularly great because it consumes so much water and it comes from different parts of the world, that it's negative to the earth and it's consuming a lot of water, and it's traveling halfway around the world to be processed into something.

Whereas one of the other benefits we found with this polymer made from sugar beets, the nature of sugar beets is it's positive to the earth. We didn't know this when we started. We've since come to understand that the material itself is very good. It's very low-water usage, high-density, meaning you can get a lot of crop in not as much space. It's neutral to the ground. Meaning traditionally with agriculture, you might have a crop that has three seasons of growing, and then the fourth season, you leave fallow for the earth to recover its nutrients or you put a completely different crop in there to effectively add that nutrients back in.

There's inefficiency there. With sugar beets, you can grow it for more than three, four, five, six, seven seasons continuously, or you can take it out and immediately put another crop in there.

ezt: Are these records compostable?

kd: Yes. You can fully recycle them. In the same way that it's common practice in the industry to regrind old records, PVC records, the waste from the process, and then make new records again, you can do exactly the same with the plant-based sugar beet material as well.

ezt: If you stuck it in the dirt for a year, what would happen to it?

kd: Well, the first thing to say is if you stuck it in the earth, it's not going to be toxic to the earth. That's very important. For it to eventually decompose and recycle back into the earth itself, if you left it as a full record, it would take a very, very long time, more than our lifetime. You'd be smarter to grind it up first, and then it will dissolve quickly.

The upside of that is in the testing that we've done, and just to be clear, we've put this material through exactly the same test as PVC is in terms of things like hardness, rigidity, flexibility, wear in terms of playback wear, things like that, heat resistance, all the rest of it. It scores exactly the same, and in some cases, some of the tests are a tiny bit better than PVC. Of course, we can't wait 40 years and see if the records still work.

In terms of the testing, the hardness testing that we've done, the longevity testing that is possible in a lab, it performs just as good, if not better than PVC. We know that if you store it on yourself like any record, it's going to last exactly the same way. If it did end up in the ground, we're not doing any harm to the earth, which is, again, a bonus.

lj: The thinking about records has changed even over the past five years. For example, Evan, I guess you consider yourself a little bit of an audiophile, right?

ezt: Sure, I'd have to say that.

lj: Five, six years ago, 180-gram was such a big deal, right?

ezt: Right.

lj: The thinking was, well, the weight adds to the quality, which not necessarily in terms of the sound. Imperfection could happen all throughout that whole process of making the final record. In the sense of sustainability, use less material, which is good for the food chain. It's less of a big deal. The other thing I was going to point out is a government at RPM, and I bought this record actually in London at Rough Trade in August 2022. They had the soundtrack album of Greta Thunberg's documentary. She's pretty much the face of climate change activism. I bought the record and I was like, "Amazing." Everything about the packaging was green, recycled paper, recycled inks. Plant-based things. The record itself at that time was recycled PVC.

One of our plans is actually to get in touch with Greta Thunberg and see if we could press a record on the plant-based material and really walk the talk here with a record.

ezt: Yes. Well, and back to your 180-gram comments. Last week, I was listening to a Dynaflex pressing from the '70s and they were a way to save some money on PVC in the '70s, the RCA company famously created Dynaflex which was extremely thin vinyl. Some of them sound really good. A lot of Bowie's records were on Dynaflex.

lj: I think of Young Americans immediately.

ezt: Yes. I was enjoying a Jerry Reed record last week and it was on Dynaflex, and it sounded great. Thickness doesn't necessarily equate with better audio quality all the time.

kd: I completely agree with that, because I'm involved day-to-day in actually pressing records in different factories and I've gotten to understand what are the big factors in the outcome, the actual quality of the record. For me, I know there'll be people out there that swear by 180, even 200-gram records, but actually, the path to ultimate quality starts with the recording itself, of course, the quality of that recording and the mastering is usually important, but then where it can all go horribly wrong or fantastically right is in the cut to lacquer.

The pitch control and, really, the depth, width, and spacing of the grooves is really fundamental to that quality of sound and the loudness of the record, which to the layperson listening will really have an impact in the result and quality, or at least the perception of that. It's really the chain of events that start well before the pressing and certainly are, as if not, I would say more important than the weight of the record itself. You can have a terrible sounding 200-gram record and an amazing sounding 120-gram record and everything in between.

It really is about the cut I think is super important, the galvanics process, of course, and it all starts with a mastering. I suspect your Jimmy Reed record is because it was recorded fantastically and cut beautifully. That's why those Blue Note records will still be pressed in a hundred years' time easily because the original, the quality, and the sound staging of the original recording and the mastering was just exceptional. Everything is so well spaced out in the music that you have to-- I mean it's possible, but you have to try extra hard to mess it up when you press it.

ezt: Don't forget with 180-gram or 200-gram, depending on your turntable, you might have to adjust your VTA.

Larry, tell me a little bit about the-- now it's not open yet, but you do have an actual structure. There's a building that you--

lj: Yes. I wanted just to back up a little bit about. In January of last year, Kevin and Gummi and I decided we were going to take a trip to Iceland, the three of us. The first business meeting we had was in Reykjavik in March 2024 with something called the Iceland Eco-Business Park. In 2008, when the economy collapsed very suddenly, one of the casualties of the economic collapse was an aluminum smelter who-- there was already Alcoa, which was very controversial business operating-- American company operating in Iceland. The environmentalists were really angry about it. In fact, Björk herself was at the site protesting.

Around the same time, she and Sigur Rós did a concert that was televised on national television in Iceland, a concert in support of the environmentalism. It turned out about 10, 15 years ago, the government ended up buying this half-completed cement building that is the length of two football fields.

ezt: That's big.

lj: There were two individuals who were basically charged with turning this into an eco-friendly operation. One of them came from the fishing industry, which is the biggest export in Iceland. The other came from the airline industry. They were saying, "We know we could get those types of businesses involved, but we're known for culture. In the arts, then we need something like that." Then somebody said-- Gummi's sister-in-law worked for a business development organization in Iceland, and she connected us with-- they found out about us through his sister-in-law.

Kevin, you probably agree with me. It was the greatest moment to see that there was a stereo set up in the conference room that probably never had the stereo before, but to impress us that we think what you're doing is a really great idea.

kd: I think that's interesting to place what we're doing in a wider context as well. This might sound like lofty ambitions, but genuinely, we are coming from a place of love of records. The one thing we all have in common is we absolutely love records as a format and we love music, but also thinking how can we doing what we are trying to do have maybe positive repercussions for other industries, for other communities. Essentially we're making something out of plastic. We started with making records because we love records, but the implications of what we're doing with the material itself grow beyond that.

The biggest consumer of PVC in the world is construction materials. The second one after that is PVC for cabling. We're already working on formulas for the-- tweaking the formula for use in construction materials and that, which is among-- those absolutely dwarf the record industry in terms of record manufacturing.

lj: Sure.

kd: Same for the process itself. How can we demonstrate what's possible with manufacturing in terms of optimizing? All that aside, bottom line is we just feel incredibly lucky that we get to make records, whether it's made from plants or it's got a smart vinyl element to it. In some ways, it might sound crazy that I'm saying this. In some ways, none of that matters as long as I get to make a great record and I can listen to it and enjoy it. Everything else is a huge bonus. What I'm saying, I'd ask you this if-- I haven't had chance to ask you any questions, but I want to ask you one, which is your perspective on, I guess, the market, and maybe in terms of artists and labels, because it's one thing us wanting to do it because we're true believers, I guess.

I come from, myself, a renewable background, and Larry is an encyclopedia of records and a love of the culture. There's no point us doing this if no one wants it. It's important to know that there is a market for what we're trying to do. The confidence I take is, when you read about, hear or speak to artists and labels, the great thing about music and the music industry in terms of those involved in it, there's a bigger predisposition towards supporting sustainability, supporting progressive ways of innovating what we all love.

I would ask you, I totally see you as a uber-consumer of records, if you like. What gets you out of bed other than the music itself? What are the factors that get you interested or you care about as a consumer of records?

ezt: That's a good question. I think that I appreciate a well made package. I think there's a lot of talk about cost as far as vinyl records are concerned nowadays, which some of it is probably a little blown out of proportion. I think you just want to see value. You feel like you want to pay for something and then get something that's really good in return. There's nothing worse than maybe-- obviously I buy a lot of used records too, which I think is its own sustainable way of-getting into records, but there's nothing worse than buying a new record, and particularly at a place that you can't return it.

If you're buying something online and you get it and it's in rough shape when you open it up, you have some ability to return it somehow. Let's say you're at a show and you buy-- the artist has some records for sale and you bring it home and there's a defect, or it's just a really lousy sounding pressing. That's a really unfortunate situation for me because you just don't have an opportunity to really recoup the money that you put into it.

I think for me a consumer, I look for a value. Even if I'm spending money on something, I want it to be what it purports to be. Back to what you guys are doing, I think the sound quality is really important. I think that'll be important to people. I think both consumers and artists, as Larry pointed out, are definitely going to have a feeling of wanting a product that has a sustainable component to it. I think that for those consumers, that's certainly going to be an important selling point.

lj: There are two research studies from 2024 that show, especially Gen Z, care about sustainability, and willing to pay more for a record in particular. Key Production in England did a a research study of that and found that 71% of Gen Z was willing to pay. The other demographics actually were healthy percentages. Going to even my baby boomer group, a little under 50%.

ezl: You're not a baby boomer. Come on. You're an X, generation Xer.

lj: I'm a young baby boomer. That was true on the packaging side too. I think you're absolutely right. The packaging is very, very important. That's really good to know-- we have to look at the Gen Z type artists, like with Billie Eilish who care about this stuff. It's not only her, Phoebe Bridgers. I'm sure there's plenty especially on the indie side of the music business.

The other thing that-- the second meeting we had by the way, was with Siggi, the drummer of the Sugarcubes. He's a senior advisor of Iceland Music. He immediately fell in love with the whole concept. He said to me, "I'm going to be in New York next month. You want to get together?" I said, "Yes." At that point, I really boned up on the whole Sugarcube's catalog. On that second album, there's a song called "Dear Plastic", and it's Bjork complaining about all kinds of plastic.

Anyway, I said to Siggi, "I want this to be one of our first records." He said, "That is a brilliant idea. I will bring up with my former band mates." Then in early October, I went back to Iceland. This was basically setting up the launch of the record that Kevin and Gummi oversaw at Airwaves. Siggi came back to me and he said, "All right. This is what Bjork wants to do. She wants to get a remix done of the song, and then on the flip side, they'll figure out a live track, something unreleased." Which from our perspective is great because it creates an entirely new product both sides. That's something we have to look forward to pressing this year.

Kevin DaCosta, Larry Jaffee, and Gudmundur (Gummi) Isfeld

Kevin DaCosta, Larry Jaffee, and Gudmundur (Gummi) Isfeld

ezt: I really thank you for taking time to talk about this with me. I think for listeners, it's also a deep dive just into the direction of sustainability in vinyl and where it's going. This is as I said, using an actual vegetative material to create these discs and have them sound good is really a pretty fascinating thing. Thanks for sharing the process with me, and I wish you the best of luck. I got to get over there. I got to get to Iceland and see this thing when it is up and running.